Palais des Exposé 2321

House in Laguna 002 2322

Working Title Museum 001 2323

Working Title Museum 002 2324

Working Title Museum 003 2325

Working Title Museum 004 2326

Ludi 002 2329

| |

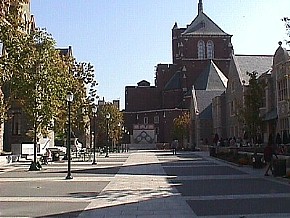

Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates, Perelman Quadrangle (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1994-2000), images: 2001.10.21.

Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates, Williams Hall Alteration (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1994-2000), images: 2001.10.21.

MVRDV, Costa Iberica (Benidorm, Spain: photomontage, 2000).

| |

Guggenheim Reenacts the Vatican

2000.01.20

Saarinen, Kahn and the Use of History

Steve asks:

. . . the spiral entry ramp of the Vatican Museum. How come no one ever acknowledges that that spiral ramp and the skylight above it is exactly what Frank Lloyd Wright copied (or should I be kind and say reenacted?) when he did the Guggenheim Museum on 5th Avenue?

Paul replies:

I don't think Wright had sufficient interest in history to have known about European precedents. He was adamantly All-American, at his worst an obnoxious know-it-all in the good ol' American "Know Nothing" tradition (except for his Japanesque tendency). Had Wright looked around Europe more he might have found a precedent in the double-helix marvel at Chambord.

Steve replies to the reply:

In all respect for your experience and generally thoughtful writing, Paul, your response vis-à-vis Wright's insufficient interest in history is dumb because the proof that Wright or someone in his office very well knew the Vatican ramp and skylight is the ramp and skylight of the Guggenheim in New York itself--the skylights are virtually identical, and the only difference between the two ramps is that Wright's ramps take on a greater diameter as it raises. Moreover, your bringing up Chambord confuses (or is it obfuscates) the issue. Basically, the prior existence of the Vatican ramp in conjunction with skylight proves Wright's "All-Americanism" as the myth it is. Furthermore, Wright's control over everything may be a myth as well. I doubt that the Guggenheim's themselves were unaware of the Vatican ramp (which may explain the connection if Wright indeed never entered the Vatican Museum that way). I fear that the way you describe Wright's attitude above more aptly describes your attitude (in this case at least).

| |

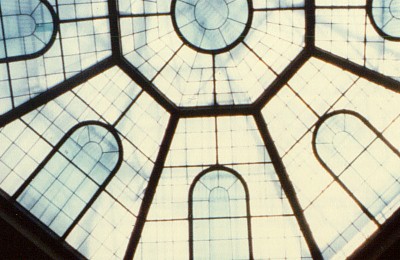

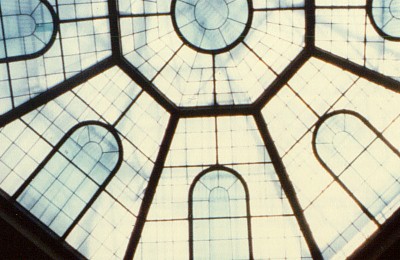

Guiseppe Momo, Entry Hall of the Vatican Museum, 1929-32, detail of skylight.

|

| |

Frank Lloyd Wright, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1943-59, detail of skylight.

|

The fact that you make several huge assumptions above, particularly in the face of some strong physical evidence, really makes me wonder about the general truthfulness (objectivity) of your convictions. Anyway, I find that the reality is always far more instructive than the myth.

2000.01.20

Wright and historical method

Paul, thanks for a more thoughtful reply re: the Vatican ramp and Wright's Guggenheim. I'll only pick on one part of your reply, when you say:

why would Wright--who maintained that he was the consummate creative genius, He who Let There Be Architecture--all else being deficient--why would the self-proclaimed artistic loner risk his precarious (as that stage) reputation in history by copying a ramp at the Vatican Museum? It doesn't make sense to me.

I don't think the workings of logic or sense making necessarily help here, and, ironically, it doesn't seem all the logical for one to admit Wright's charletanism, his PR tactics, his spin-doctoring, and the skepticism of his after-the-fact accounts, and then to draw a rigid line by saying, but Wright would never, ever copy and/or find design inspiration in a European architectural precedent.

I have nothing against Wright or his architecture. In fact, I feel very lucky to live not far from his Beth Shalom synagogue, a real masterpiece. But I don't like to see personal opinion or even accepted scholarship get in the way of understanding creativity and the creative process (as opposed to the 'fabrication' of creative genius). In this particular case of the Vatican and the Guggenheim I see a very interesting example of creative mimesis, and even some very creative reenactment. I'll explain below.

As I walked up the Vatican ramp that first (and so far only) time in 1977, I remember thinking, "wow, this is just like the Guggenheim." I then wondered if Wright had ever been in the same space. Such a connection had unorthodox connotations (as this thread of posts attests), but alas, one will probably never really know. Only when I looked up at the skylight and instantly recognized the obvious similarity between the Vatican skylight and the Guggenheim skylight was it then that I became convinced of the extreme likelihood that Wright very much knew of the Vatican space (be it either by having been there himself, or by drawings and/or photographs).

| |

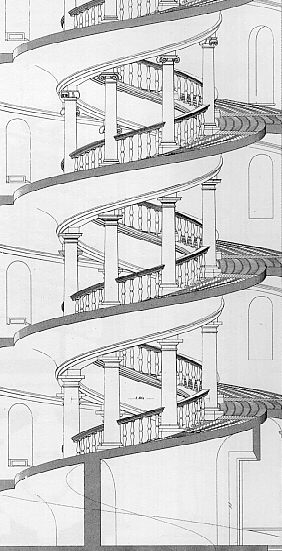

Giuseppe Momo, Entry Hall of the Vatican Museum, 1929-32, view down into the hall from above.

|

I will now get very 'Freudian' here, and say that just maybe the Guggenheims, like Freud, had this strange love/hate thing vis-à-vis Rome/the Vatican. After all it was Freud, a Jew, who reenacted the Christian Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit by instituting the ego, id, and super-ego. So, one could then imagine the Guggenheims saying, "Mr. Wright, we want you to build for us a Jewish Vatican museum!" And lo and behold, Wright, creative genius that he was, designed the foremost Jewish Vatican Museum in existence, with no one ever being the wiser--quite an accomplishment, (or did it all just happen subconsciously?). [I better stop before I start writing a reenactment novel here.]

| |

Frank Lloyd Wright, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1943-59, view down into the museum from above.

|

Anyway, I think there is a lot more to learn about how 'design' happens by looking at the potential relationship between the Vatican entry ramp and the New York Guggenheim, especially in noting how Wright's design deviates from the Vatican model, then there is to dismiss the relationship because of its contrariness to received (but not necessarily fully disclosing) opinion.

In 20th-century American architecture: a traveler's guide to 220 key buildings (1993), Sydney Le Blanc describes the interior of Frank Lloyd Wright's 1949 V.C. Morris Gift Shop as a "design [that] practically guides you through the shop by means of a spiral ramp, a precursor of Wright's integral design for the Guggenheim Museum in New York City some twenty years later." In truth, the design of the Guggenheim Museum with its interior spiral ramp dates from 1944, although the museum did not begin construction until 1956. At best, the C.V. Morris Gift Shop is a contemporaneous, diminutive spin-off of the Guggenheim Museum.

Frank Lloyd Wright, V.C. Morris Gift Shop, 1948-50, three interior views.

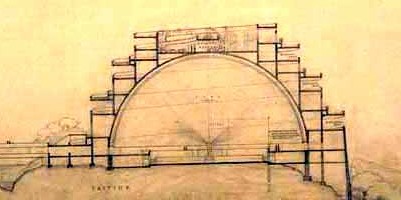

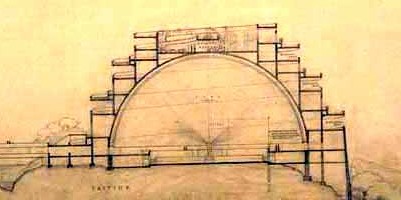

The design from Wright's earlier career that comes closest to precursing the Guggenheim Museum is the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective (1924-25), which incorporates a spiral automobile ramp that wraps around the summit of Sugar Loaf Mountain, Maryland. The ramp is here on the exterior of the building however, thus preceding the Guggenheim Museum in an inversionary fashion.

| |

Frank Lloyd Wright, Gordon Strong Automobile Objective, 1924-25, view of the design model.

|

The section through the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective denotes the obvious difference between it and the Guggenheim Museum, but it also indicates just how close the two designs are in that it is not difficult to imagine the ramps of the Sugar Loaf Mountain design being an integral part of the building interior. On its own, however, the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective seems a distant descendant of Boullée's Newton Cenotaph.

| |

Frank Lloyd Wright, Gordon Strong Automobile Objective, 1924-25, section.

|

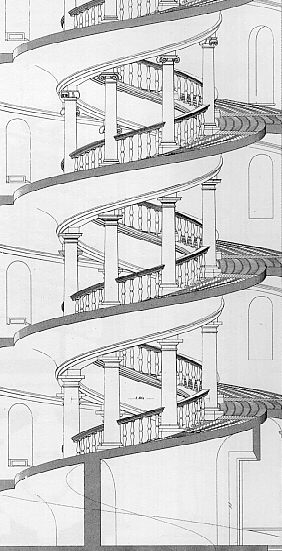

In The Architecture of Rome (1998), Stefan Grundmann begins describing Giuseppe Momo's Vatican Museum entrance hall with ramps as "a curiosity in terms of architectural history." Ramps are here taken for granted as distinctly modern architectural elements, yet the Vatican of the early 20th-century was hardly an advocate of the modern. What makes Momo's design even more a curiosity however, is that two ramps, a double-helix, are employed, with one ramp for access and the other ramp for egress.

| |

Giuseppe Momo, Entrance Hall of the Vatican Museum, 1929-32, view up into the hall.

|

That Grundmann's further description of Momo's ramped hall actually devotes more words to Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum is a clear indication that the two buildings are virtually identical. Nonetheless, it is pointed out that "Vatican architecture served as a model once more, but it no longer pointed the way forward."

[It should be noted that Grundmann's text regarding the Momo/Wright connection reenacts Vincent Scully's text (in American Architecture and Urbanism) regarding the same Momo/Wright connection.]

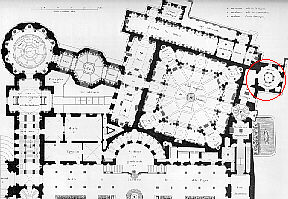

What has not been mentioned thus far is that Giuseppe Momo found a precedent for his rising spiral design in the Vatican Museum itself. There is a spiral 'staircase', designed by Bramante c. 1504, which allowed individuals on horseback access up to the Vatican's Belvedere Palace (which today comprises much of the Vatican Museum) from the street level several stories below.

"Next to this courtyard [the octagonal courtyard of the Belvedere Palace] Bramamte built a spiral ramp-staircase which exemplifies some of his most characteristic concerns. Spatially its basic idea is simple: a hollow cylinder containing a spiral supported on columns with architrave. The spiral is a rigorous mathematical form, suggestive in itself of upward movement and of continuous ascent, and therefore eminently suitable for a staircase. Spiral staircases had been built by Francesco di Giorgio in Urbino and designed by Leonardo in Milan. Spiral staircases on columns had sometimes been used in the Middle Ages, and their architectural authority was confirmed by at least one Antique example -- the so-called 'Portico of Pompey', which was drawn a number of times during the Renaissance, and, according to Palladio, was the source of Bramante's idea."

Arnaldo Bruschi, Bramamte (London: Thames and Hudson, 1977), pp. 108-09.

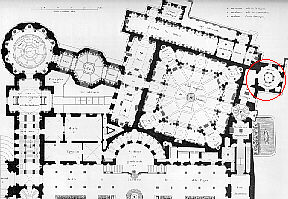

| |

left: Donato Bramante, Staircase of the Belvedere Palace, c. 1504, section through the spiral staricase.

above: Belvedere Palace, plan indicating the position of Bramante's spiral staircase.

|

|