Vincent Scully, Jr., Louis I. Kahn (New York: George Brazilier. 1962), pp. 23-5.

| |

It is therefore apparent that Kahn, by 1955, had worked himself back to a point where he could begin to design architecture afresh, literally from the ground up, accepting no preconceptions, fashions, or habits of design without questioning them profoundly. That "great event," so rare and precious in human history, when things were about to begin anew almost as if no things had ever been before, was on the way. On the other hand, memory would eventually play an important part in the process, most richly and intensely for Kahn; but it would come only when the first major steps to liberate the mind for it had been taken. First would come a na´vetÚ of vision which most men can never achieve and only the most intelligent can imagine to be possible. Nothing would be taken for granted. (Even though Kahn was to say to the editor of Perspecta, 7, "I have the usual artful fainting spells, you know.") Every question would be asked: What is a space, a wall, a window, a drain? How does a building begin? How end? Every expedient dodge and avoidance well known to the dullest student in second-year design was henceforward normally to be impossible for Kahn. He was beginning where almost nobody ever gets to be: at the beginning.

It is possible that in modern architectural history before Kahn only Frank Lloyd Wright ever began so wholly at the beginning. Elsewhere I have tried to show that an extremely close parallel exists between Wright's works of 1902-6 and Kahn's of 1955-60. I shall therefore refer to but not stress that relationship here. It should only be pointed out that anything of the kind has been wholly unconscious on Kahn's part. He has said that he was never consciously influenced by Wright, and I do believe him in this. Again, such makes the parallel all the more significant; perhaps it indicates a general pattern that occurs when the problem of architecture is studied afresh by a mind which intends to know the whole. Secondly, Wright and Kahn have occupied rather similar historical moments and have functioned in the same way in them. Both, that is, began their invention--Wright early in life, Kahn late--at a moment when the general architectural movement was toward clear geometric order: in the forties and fifties late Mies and Johnson, in the eighties and nineties Richardson, Sullivan, Burnham, and McKim. In the nineties most architects soon came to conceive of such order in the usual Picturesque-Eclectic terms, and the movement as a whole turned into neo-Baroque formalism, overtly eclectic, overtly decorative. Wright conceived of order in intrinsic terms and rebuilt architecture from the ground up with it. In the fifties-after Mies--some of Johnson's work, almost all of Stone's, Yamasaki's, and others has followed the first course, the neoBaroque, decorative one. Kahn has followed the second: Wright's course. The first course heralded, in the nineties, the end of something; in the late fifties it would seem to have been doing the same. The impression becomes inescapable that in Kahn, as once in Wright, architecture began anew.

| |

2002.08.09 15:20

Re: Congregation or Synagogue ?

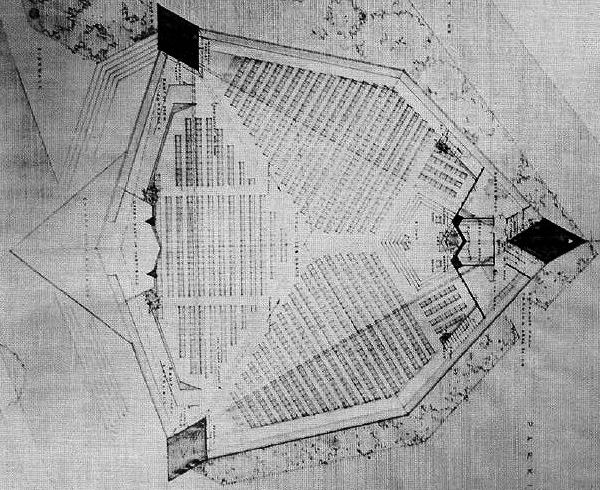

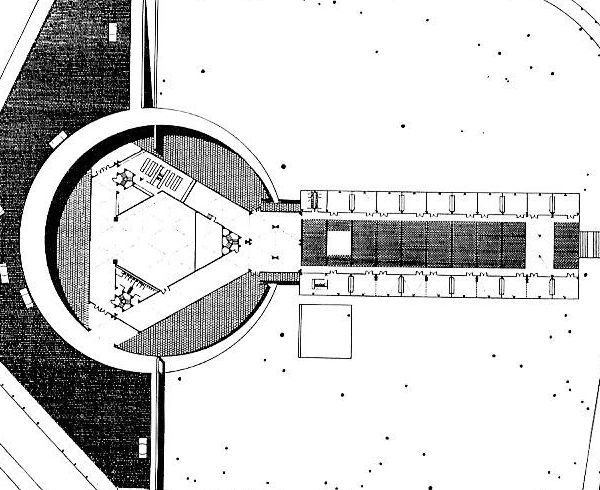

It dawned on me last night that both Wright's Beth Sholom and Kahn's Adath Jeshurun are hugely triangular in plan. Wright mailed the preliminary drawings to Rabbi Mortimer Cohen on 15 March 1954. Kahn's design is dated 1954-55. Since Beth Sholom and Adath Jeshurun are neighboring congregations, it wouldn't surprise me at all if architectural rivalry between the congregations was going on, and that Kahn even saw the Wright plans before he came up with his design. Has anyone heard of this possible connection before?

2002.08.11 10:44

Kahn and Wright

Here is excerpt from Louis I. Kahn: In The Realm of Architecture (1997) with some commentary following:

on pages 79-80: Documented evidence of ties between Wright and Kahn is slight. His connection with Henry Klumb (1904-1985), a former associate of Wright's and a staunch supporter of his ideals, is noted in chapter 1. In 1952 Kahn and Wright both attended a convention of the American Institute of Architects, in 1955 (as previously noted) Kahn praised Wright's early work, and when Wright died in 1959 Kahn wrote in tribute [published in Architecture Record], "Wright gives insight to learn / that nature has no style / that nature is the greatest teacher of all / The ideas of Wright are the facets of his single thought." Scully recalls that later that same year Kahn made his first visit to a Wright building, the S.C. Johnson and Son Administration Building (1936-39), where, "to the depths of his soul, [he] was overwhelmed."

It is curious in that the Scully quotation (from Scully's book Louis I. Kahn (1962)) seems to harbor a mistake, a distancing, and/or perhaps even an intentional fabrication. I, for one, find it hard to believe that Louis Kahn never visited Beth Sholom prior to late 1959, thus I doubt very much that it is true that the first Wright building Kahn visited was the S.C. Johnson building in Wisconsin. Now I have to wonder about Scully and Brownlee/DeLong (authors of Louis I. Kahn: In The Realm of Architecture). Was Scully or even Kahn(!) fabricating a false history that would distance Kahn safely away from being suspected of having ever been really influenced by Wight? And why did Brownlee/DeLong not notice and/or correct what appears to be just plain false? The only real reason I'm pointing all this out is that I believe it is much more valuable to know how designs really came about rather than how they really didn't come about.

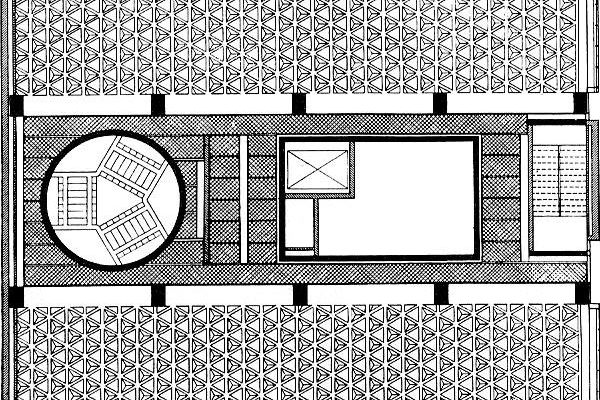

This leads me to bring up the anecdote R. shared here as to what Wright said to Venturi about Kahn, i.e., "Beware an architect with one idea." If Wright said this to Venturi circa 1955 (date of Beth Sholom construction), then the "one idea" Wright was speaking of may well be the Yale Art Gallery (1950-53). The Yale building is the first to get Kahn wide recognition, particularly for its triangulated ceiling structures, a structure, moreover, that Kahn further investigated in the second scheme of Adath Jeshurun. Furthermore, the second scheme of Adath Jeshurun is remarkably similar diagrammatically to the stairwell plan within the Yale Art Gallery, i.e., a triangle within a circle.

Could it be that Venturi told Kahn what Wright said, and that is perhaps why Kahn wrote "The ideas of Wright are the facets of his single thought"?

|