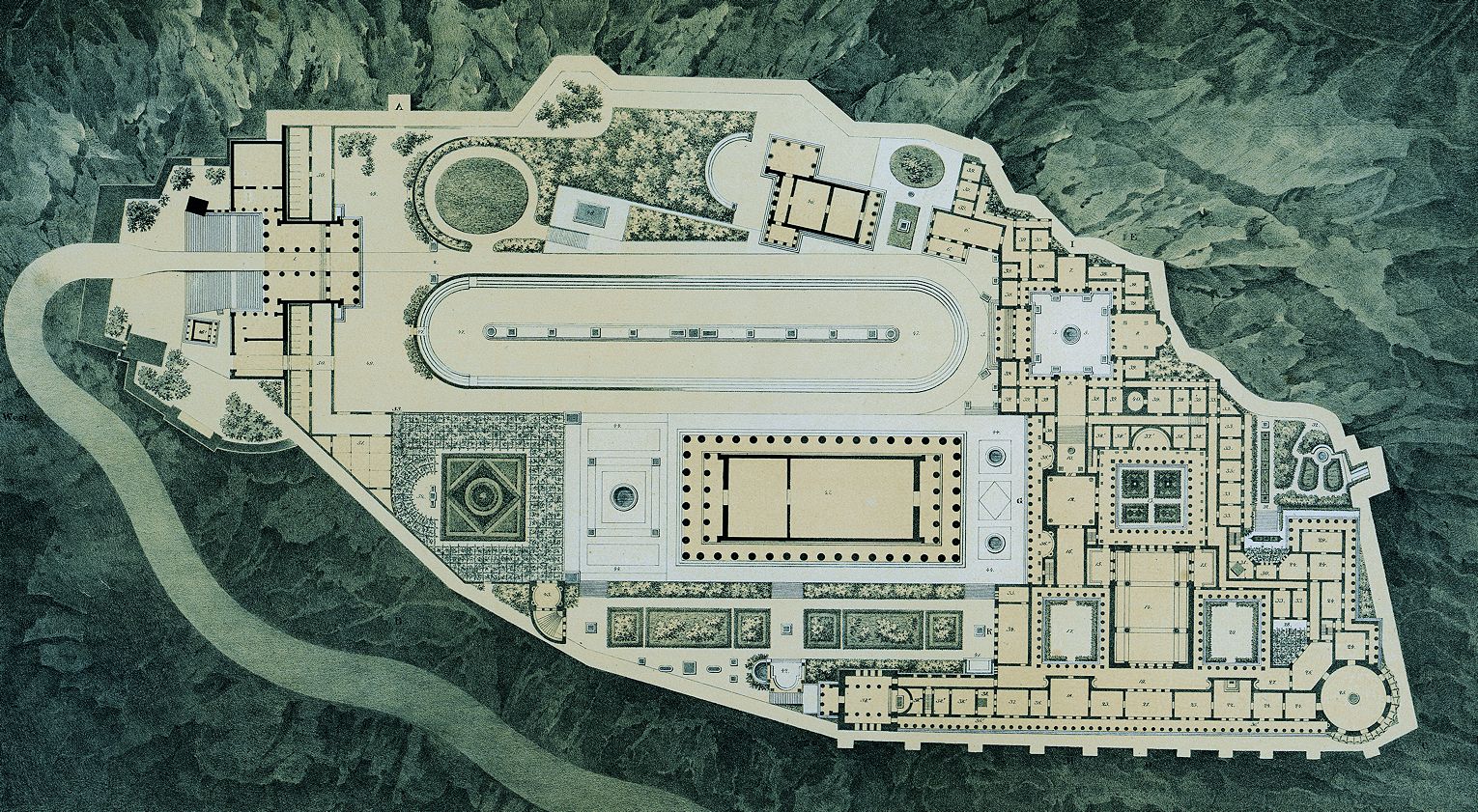

schinkel | Palace on the Acropolis Athens 1834 |

|

Already during the presidency of Capodistrias German architects had begun to practice in Greece. Stamathios Kleanthes, Thessalonikan by birth but one-time student of Schinkel, and the Breslauer Eduart Schaubert arrived in Greece from Berlin and went to work in Aegina. After the assassination of Capodisrrias there was considerable talk about making Athens the new capital and, with an eye for the main chance, these two Berlin-trained architects moved there, surveyed the city, and prepared a plan for its enlargement that included a royal palace. |

Athens was by no means an obvious choice for the new capital as the city survived as little more than a name. A few modern houses existed among the scattered ruins of a remote past. The Greeks of the Peloponnesus who were promoting Corinth as the capital pointed to that city's splendid location on the Isthmus and to the center of the kingdom as its borders were then defined. Some optimists even proposed Constantinople as the capital, but the most realistic proposal was that of the Bavarian architect Johann Gottfried Gutensohn who urged a site beside the port at Piraeus from which the court could make a quick getaway in time of trouble. In the end the powerful allure of Antiquity proved irresistible, and by the autumn of 1833 it had been decided that Athens should become the capital.5

|

The young King Otto lived for the first two years (1832-1834) in the house built for Capodistrias in Nauplia. His first visit to Athens was in May 1833 when he and his brother Maximilian, Crown Prince of Bavaria, were taken around by Ludwig Ross, the great classicist who was later to attempt a restoration of the Nike Temple on the Acropolis.6 At the time of their visit there was still a mosque within the Parthenon and military barracks and powder magazines close by.

|

On his return to Munich Max related his experiences to his old friend from the University of Berlin, Friedrich Wilhelm, Crown Prince of Prussia.7 Friedrich Wilhelm, himself an amateur architect, was struck by the idea of a royal palace on the Acropolis and suggested the leading Prussian architect and his sometime collaborator Karl Friedrich Schinkel as the man to design it, overlooking the prominent Munich architect Leo von Klenze, who in the next year would arrive in Athens to play a dominant role as architect. Max wrote to Schinkel asking his advice concerning the appropriate architectural style for modern day Greece and more particularly for advice concerning the idea of a royal palace in Athens. The immediate reply was in general terms.8 Only later when Friedrich Wilhelm assured him that Max was not only serious about such a palace, but awaiting plans from the architect did Schinkel begin work on the project, devoting to it the early morning hours, the only ones left to him by his official responsibilities as Oberbaudirektor and head of the new Architectural Academy (Bauakadernie).9

|

Schinkel was only 52 at the time, but the last ten years before his death in 1841 at the age of 60 were spent in failing health. After 1837 paralysis in one hand often prevented him from drawing or writing. As a result, his acrivities as a practicing architect--though not his official duties as Oberbaudirektor and professor--were greatly reduced. His major executed project of the 1830s was the Bauakademie begun in 1831 and completed in 1835, This large brick building of utilitarian character in the heart of Berlin offered as striking a contrast to his earlier monumental classical buildings in the neighborhood as it did to the contemporary grandiose scheme for Athens. In the light of the influence the Bauakademie had on later public buildings in Berlin--such as schools and hospitals--and the debt it owes to the industrial buildings Schinkel had observed and sketched in England, many recent critics have considered

the Bauakademie to be Schinkel's crowning achievement whereby he left Neoclassicism behind and stepped into the

modern world.10 These "modernist" apologists for Schinkel are usually embarrassed trying to account for the project of

a royal palace on the Acropolis that he was working on at virtually the same time; yet Schinkel was as serious about the project as were his royal patrons.

|

www.quondam.com/54/5427b.htm | Quondam © 2017.01.09 |