Catalogo:

Circo Apollinare. «Liv. nel. lib. 3.» Veggesi Circo Flaminia.

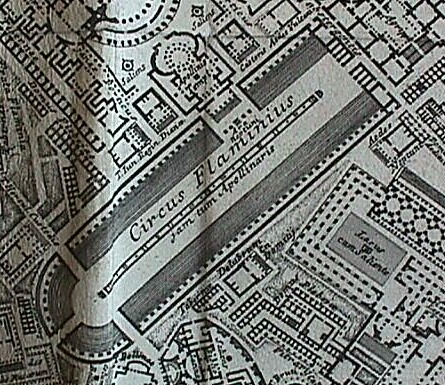

Circo Apollinare Flaminio, « Liv. nel lib. 3 ed 8, l'epitoma del lib. 20 del medesimo Dione nel lib. 55, la sua epit. in Augusto, Plutar. in Silla, Fulvio ed il Ligorio.» Si riferisce nel cap. 4, art. 1. Ve ne rimangono aleune vestigie che si dinotano nella Tav. 2, presso il num. 18 nella 4 e suo indice col num. 55, e si dimostrano in prospettiva nella Tav. XVII.

Oriuolo nel circo Flaminio. «Vitruvio nel lib. 9 al cap. 9.»

Fabbriche del vetro nel circo Flaminio. «Marziale nel lib. 12 epig. 75.»

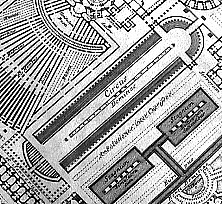

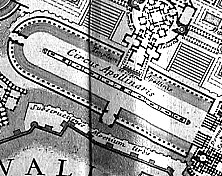

Circus Flaminius as delineated within the first state of the Ichnographia Campus Martius. Note the included Ara Neptuni which is not delineated within the second state of the Ichnographia Campus Martius.

The circus Flaminius. As early as 221 B.C., C. Flaminius Nepos, while censor, erected in the south part of the campus Martius his famous circus, which was for many years the most conspicuous building in this section of the city, and gave its name first to the immediate neighborhood and afterward to the whole ninth region. Its site is now entirely covered with modern houses, and no traces of the circus itself are visible; but its exact position is known from the descriptions of writers of the sixteenth century, at which time large portions of the first story were still standing. The length of the circus was about 297 meters, its width about 120, and its main axis ran nearly east and west. It appears to have been built according to the plan adopted in later structures of a similar nature, and its lower story opened outward through a series of travertine arcades, between which were Doric half-columns. In this circus the ludi plebeii and the ludi Taurii were celebrated, and its proximity to the centre of the city made it a favorite place for holding assemblies of the people and for markets.

(Platner)

Vincenzo Fasolo, "The Campo Marzio of G. B. Piranesi".

2691a

1956

Tafuri text

1996.09.02

Pictorial Dictionary notes

1997.08.23

Circus Flaminium is misorientated within the Ichnographia, but, judging from the Forma Urbis fragment, it is not obvious as to its orientation vis-à-vis the Theater Marcellus.

Obeliscus Hortum Sallustianorum, found in the Ichnographia, but it is positioned at a polar opposite position. Is Piranesi playing some kind of mirror game? (because he occassionally performs the same type of inversion with other buildings/remains, e.g., the Templum Metidia and the Circus Flaminia)

life, death, and the triumphal way [inversion]

1998.01.11

I spoke with Sue Dixon yesterday and told her of my latest "discoveries" regarding the life and death axes of the Ichnographia, the arch of Theodosius et al and the further symbolism of the Porticus Neronianae as an inverted basilica-cross. She too became excited by my discoveries and then also brought further insight, especially in reference to the issue of the papacy and its research during the eighteenth century into the early Christian Church. She spoke of Bianchini and his nephew (a contemporary of Piranesi's) and their dual volumes of pagan (Roman) and Christian art, and she also mentioned how the papacy of the eighteenth century had lost (more or less by force and financial restraints) much of its political power and thus took on a very pious role--exhibiting not its worldly power but its almost mystical or spiritual power.

What I was saying about the apparent Pagan-Christian conversion-inversion narrative of the Ichnographia fit with what research Sue is continually doing regarding the contemporary and early eighteenth century influences on Piranesi and the whole issue of proto-archeology - history of the eighteenth century.

After speaking with Sue, I began thinking of the significance of the arch to the victory over Judea that is situated to the western end of the Bustum Hadriani. I now see it related to the pagan-Christian conversion-inversion of Rome, but in terms of Roman history it is a somewhat marginal issue-event. Yet, in terms of Christianity, the Roman victory over Judea, and hence the fall of Jerusalem, is a significant, albeit still sorrowful, event because of this event's relationship, and indeed verification of certain-particular passages of New Testament Scripture, i.e., Jesus' answering the Apostles question of when Jerusalem would end (which I think is in Mark or the Acts of the Apostles). Seeing how a seemingly minor event in Roman (Imperial) history can at the same time be a critical event for the foundation of Christianity made me think about how the Roman Judaic victory unwittingly gave manifest confirmation that Christianity had from that point forward absorbed Judaism.

Although it comes from the margin or edge, the significance of the victory of Judea arch sheds a major light upon the narrative Piranesi tells--Piranesi's "story" is about Christianity's similar absorption and concomitant destruction of paganism. This notion of Christianity absorbing both Judaism and paganism has major theological implications, especially with regard to a heretofore perhaps ignored importance-significance of Rome and the Roman Empire within the Canon and doctrine of the Christian (Catholic) faith.

...the real axis of St. Peter's Basilica and Square. This axis is fundamental to Piranesi' axis of life--and the most significant point alone the existing axis is the burial place of St. Peter, which, although not noted in the Ichnographia, is nonetheless an ancient Roman artifact.

...the story of the Triumphal Way. ...follow the triumphal path on the plan, and explain the entire route in Roman-pagan-triumphal ritual terms. ...bring up the essential concept of reenactment, the reenactment that Piranesi here designed, especially the well planned sequence of stadia and theaters along the way. Piranesi made use of what was actually once there.

When the route reaches the wall at the Temple of Janus, attention turns to Triumphal Arch-Gate, which is closed during the years of inactivity. Does the Triumphal Way then bounce off the wall and go back the way it came? Does the Temple of Janus allow us to go in either direction? (Other clues of inversion abound: obelisk in the Horti Salustiani, Porticus Phillippi, the Arches along the Via Lata, the Via Flaminia, the Circus Flaminia, the obelisks at Augustus's Tomb. The recurring inversion theme points to a greater meaning/symbolism.) The Temple (arch) of Janus represents the Arch of Janus built by Constantine (who might himself be called the Janus figure of Christianity) and this is the initiation of the way of Christianity's triumph: the profane to the sacred; the forest, hell, purgatory, heaven; the path of salvation through Christ and the Church.)

...the way from the profane to the sacred ends at the Area-Templum Martis as symbolic of the union of the most sacred site ancient Rome (or at least its point of origin) with the most sacred site of Christian Rome (St. Peter's place of burial) and also the point of origin of Christian Rome.

The garden of Nero is the ultimate field of inversion: Horti Neroniani to Vatican City, the garden of antichrist to the Church as the Body of Christ, the foremost seat of the Church of Christ, and finally St. Peter's inverted crucifixion begins the conversion of Rome.

I will conclude the inversion from pagan to Christian story-line by returning to the axis of death and the Arch of Theodosius et al at its tip, and thus when compared with the intercourse building we have depicted the beginning and the end of pagan Rome. To this I will add the Jewish Victory monument and end with the notion that Piranesi has here used architectural plans and urban design to tell the "history" of ancient Rome, however, one has in a sense read both the "positive" and the "negative" image-plan -- a story where the first half is the reciprocal of the second half (and vice versa). (I am oddly reminded here of the double theaters story from Circle and Oval in St. Peter's Square.)

| |

Gaius Flaminius

1998.02.15

...researched Gaius Flaminius because Piranesi's inversion of the Circus Flaminius within the Ichnographia. It turns out that Flaminius did go against the grain of the Senate and was of plebeian background. Sue Dixon also mentioned that Piranesi uses Flaminius as a point of subdivision in his Il Campo Marzio text of the districts history, (Piranesi actually thinks highly of Flaminius and his circus), and she (Sue) noted how the via Flaminia is not correctly delineated within the Ichnographia--the circus and the road were built by the same man. Perhaps Piranesi chose to delineate both these entities incorrectly to accentuate that Flaminius, in going against the grain, began a new effect on the land use of the Campo Marzio--thus showing the circus rotated 90 degrees in order to make it stand out. As for the Via Flaminia, there is no immediate explanation as to why it meanders off into a totally wrong direction, but it is worth noting the many plebeian homes that Piranesi situates along the street; this may be a reference to Flaminius' own plebeian background.

There is also the area called Prata Flaminia (within which the Porticus Philippi is situated) and I'm not sure if Flaminius also donated this land to the city/citizens.

Mistakes and Inversions

1998.02.19

...address Piranesi's own mistakes and inversions, particularly the inversion of the Circus Flaminius (which I now know to be also exchanged in location with the theater of Balba, which further shows Piranesi's intentional "mistakes" to make a specific point). [Perhaps,] Piranesi makes the mistakes, first to call attention to specific points, and second to highlight the notion of inversion. Piranesi is indeed being theatrical, which is only natural because of the whole notion of reenactment. ...discuss the Ichnographia's Triumphal Way and how Piranesi redesigns (reenacts) the Way making it more ideal to its purpose (marching through the theater district). The Way (within Ichnographia at least) ends at the Temple of Janus--a perfect example of inversion. Then following the Triumphal Way in reverse manifests the Christian theme of salvation and redemption, ending at the inverted "basilica"--the upside-down "inverted" crucifixion of St. Peter. ...the Ichnographia not only represents the history of ancient pagan city of Rome, but also the Christian city of Rome. This evokes Augustine's The City of God and also Bloomer's notion of the Ichnographia transcending time.

...the Scenographia as the stage upon which Piranesi reenacts--this is the first scene and the "play" is about to begin. In the course of the "play" the most egregious "mistake/inversion" is the misplacement and disorientation of the Circus Flaminius and its actual exchange with the Theater of Balba. This "mistake" manifests a composition of inverted theaters--essentially a double inverted theater. This configuration becomes one of the Il Campo Marzio's final scenes and thus represents the double inverted "theater" of Rome's own history--the narrative of pagan Rome and the narrative of Christian Rome, and in the Ichnographia the one story is indeed a reflection of the other.

Pagan - Christian - Triumphal Way

3123h

3123i

3123j

3123k

1999.11.21

one more Piranesian daze: circus act

2000.05.15

In attempting to discern the possible reason or message manifested by the plan changes to the Circus of Caligula and Nero and to the Circus Agonalia, I began to think of these specific circuses and how they may or may not relate to the numerous other circuses delineated throughout the Ichnographia. Within the version of the Ichnographia that is presently widely published there are six circuses, the Circus Caji et Neronis, the Circus Agonalia, the Circus Hadriani, the Circus Domtiae, the Circus Flaminius, and the Circus Apollinaris. With only minor adjustments to length, each circus is delineated in a virtually identical fashion, and, moreover, each circus reflects an archaeologically correct circus plan. As already illustrated, the plans of the Circus Caji et Neronis and the Circus Agonalia within the University of Pennsylvania Ichnographia reflect more stylized, i.e., archaeologically incorrect, circus formations. Since all the circuses are identical in the widely published version of the Ichnographia, I then began to wonder, via transposition, whether all the circuses within the Penn Ichnographia were likewise identical there in the form of exhibiting plan changes. In all honestly, I had not noticed any plan changes to the circuses other than the Circus Caji et Neronis and the Circus Agonalia the two times I had seen the Penn Ichnographia prior, but nor did I have any pictorial hardcopy evidence that there are no other plan changes. Having worked with the Ichnographia for over ten years, if I have learned anything, it is that the Ichnographia, no matter how well you think you know it, continually maintains the uncanny ability to beguile. Therefore, it was necessary for me to once more return to the other Ichnographia.

Upon doing further research, i.e., going back to the University of Pennsylvania's Fine Arts Library to again scan the Ichnographia Campus Martius, more plan changes were indeed discovered, and, just as I had begun to suspect, the "change of plans" effected the Circus Hadriani, the Circus Domitiae, the Circus Flaminius, and the Circus Apollinaris. Thus, it is now evident that each of the major "changes of plan", between the Ichnographia Campus Martius that is widely published and the Ichnographia Campus Martius within the rare book collection at the University of Pennsylvania's Fine Arts Library, occur more or less exclusively within those buildings of the Ichnographia labeled "circus".

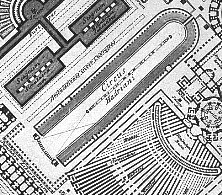

The plan above left is the Circus Hadriani as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Hardiani as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

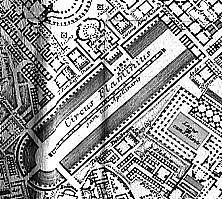

The plan above left is the Circus Domitiae as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Domitiae as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

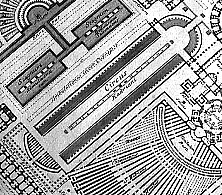

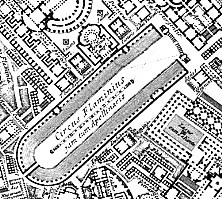

The plan above left is the Circus Flaminius as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Flaminius as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

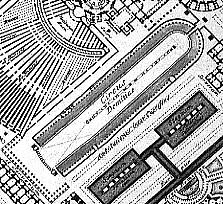

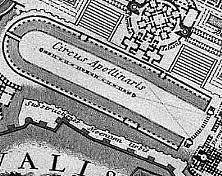

The plan above left is the Circus Apollinaris as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Apollinaris as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

As the above plan comparisons indicate, the newly discovered circus plans engage directly with their neighboring buildings, thereby rendering a connected contextualism and demonstrating a more integrated urban planning methodology. The circus plans of the commonly reproduced Ichnographia on the other hand, albeit archaeologically correct, do not engage their immediate surroundings, and appear as though literally afterthoughts. Beside the already mentioned questions as to what these changes might mean and which set of plans came first, or what Piranesi's intentions in making the changes might have been, there is now an additional question as to why the changes were specifically and only applied to the Campo Marzio's six circuses.

|