Mausoleum Hadriani. In the horti Domitiae, Hadrian began the erection of his famous mausoleum, also called moles Hadriani or Hadrianeum, which was not finished until 139 A.D. At the same time he constructed the pons Aelius. When the Aurelian wall was restored by Honorius, the mausoleum was connected by short walls with the north end of the pons Aelius and the fortifications on the left bank, and converted into the chief fortress of the city, which it has continued to be until the present time. In 590 A.D., during a plague, Gregory the Great is said to have beheld the archangel Michael sheathing his sword above the fortress. A chapel was therefore dedicated to the archangel on the mausoleum and a statue erected, since which time the building has borne the name of Castel S. Angelo.

The structure has undergone very extensive changes and many additions have been made during the past centuries, but with the help of medieval drawings and recent excavations, its original form can be made out quite satisfactorily. The lower part was a rectangular foundation or podium 84 meters square and 31 high, built of concrete with travertine walls, which were faced with blocks of white marble. The outer surface was decorated with Corinthian pilasters and an entablature, the frieze of which was adorned with garlands and ox-skulls in relief. A fragment of this frieze and one of the capitals are in the Museo delle Terme. Around this foundation was a rather wide avenue, enclosed by a low wall and a line of travertine pillars, between which were bronze gratings. On the tops of the pillars were bronze peacocks. The entrance was in the center of the side toward the river, directly opposite the head of the bridge, between which and the enclosing grating there was a street running along the river bank. The opening through this enclosing grating and the wall was triple, after the manner of a triumphal arch, the central passage being 2.40 meters wide, and the others 2.10. Over the entrance, set in the wall of the podium, was the sepulchral inscription of Hadrian; and on each side of the entrance was a row of eight inscriptions, commemorating other members of the imperial family, while that of Commodus was set above this row on the left. Of these eighteen inscriptions, twelve have been found. This great foundation is for the most part below the present level or concealed by later masonry.

On this square base stood a circular mass 64 meters in diameter and 21 high, made of concrete enclosed in walls of travertine, which was faced with Parian marble. The exterior of this drum was divided by pilasters supporting an entablature, and above this entablature was a row of statues encircling the entire building. This cylindrical portion forms the principal part of the modern fortress; but of the decoration nothing but some fragments of the marble facing remains. Above the center of the drum rose a small base, probably cylindrical, which supported a statue of Hadrian in a quadriga. The colossal heads of Hadrian and Antoninus now in the Vatican undoubtedly belonged to the adornment of the mausoleum, but we do not know just where they were placed.

From the outer entrance in the square base, an inclined way led straight into the mass for about 16 meters to a vaulted vestibule, in which was a niche where a statue of Hadrian must have stood. From this vestibule, a passage more than 9 meters high and 3 wide led upward in a spiral round the whole drum, until it reached a point directly over the vestibule. Thence it led straight into the principal sepulchral chamber in the upper part of the drum. This passage was lined with marble and paved with mosaic. The sepulchral chamber was 9 by 9 meters in area and 14 meters high, constructed of blocks of peperino and travertine and lined with the most precious marbles. In each of the four sides of the chamber were niches containing sarcophagi. The lid of a porphyry sarcophagus found here is now used as the baptismal font in St. Peter's, but the sarcophagus itself has disappeared. In this chamber were the ashes of Hadrian and probably of his wife Sabina, and of Aelius Caesar. From this chamber, and also from the spiral passage, air ducts were cut through to the outside of the drum, and provision was also made for drainage. There must have been other sepulchral chambers, but the interior of the monument has undergone such extensive changes that it is impossible to locate them. In this mausoleum were probably buried all the emperors and members of their immediate families, from Hadrian to Severus and his sons.

(Platner)

Vincenzo Fasolo, "The Campo Marzio of G. B. Piranesi".

2691a

2691b

2691f

1956

| |

The complex of buildings...

1982.03.01

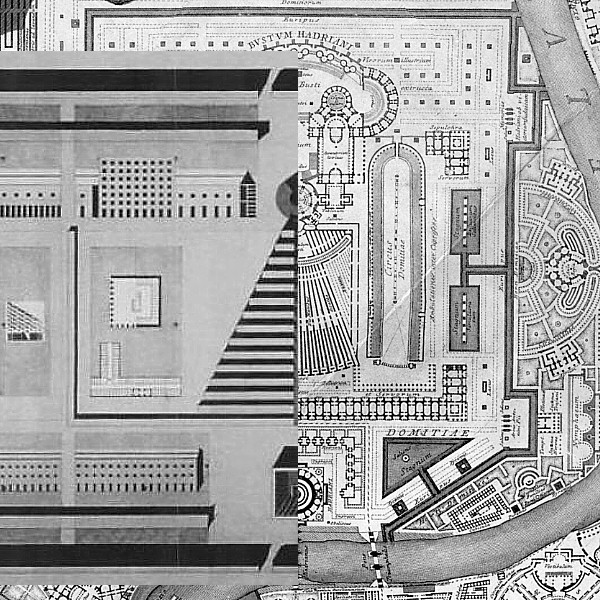

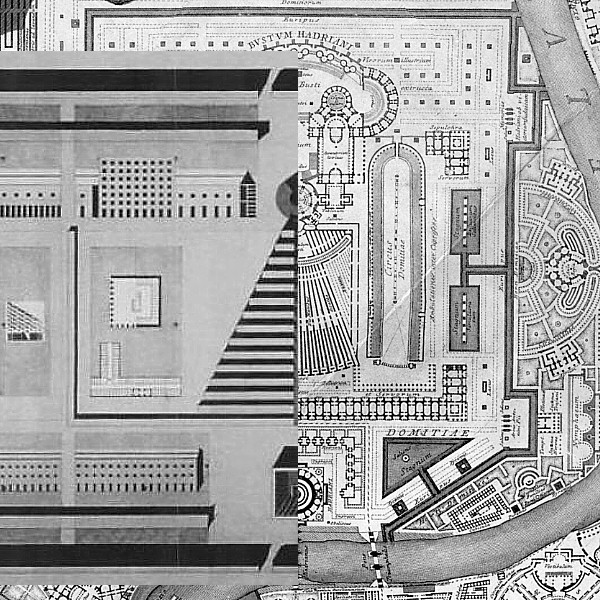

"The complex of buildings in the center of Rossi's cemetery, however, is not found in the 19th century cemeteries of the Modena/Genoa type. That idea came from another source, Giovanii Battista Piranesi's reconstruction of the Campo Marzio in Rome, as he imagined it stood in late imperial times. In Piranesi's map, a large portion of the right bank of the Tiber is occupied by a group of funerary monuments dominated by the mausoleum of Hadrian, which we now know as Castel Sant'Angelo. Hadrian's tomb sits on a square base near the river. Beyond this square is a U-shaped group of buildings marked Sepulchra. They embrace the bottom of a fan-shaped structure designated by the word clitoporticus. At the apex of the fan sits a round building called Basilica. This Basilica is part of a group of monuments labeled Bustum Hadriani, designating the place where cremation occurs. The correspondence in general layout between the Piranesi and Rossi plans is too close to be accidental. Rossi, who knew this Piranesi work perfectly well (a fragment of it appears in Rossi's drawing The Analogous City, 1976), has lifted Piranesi's vision of an Imperial ancient city of the dead within the context of late-antiquity Rome, and placed it in the middle of a 19th-century cemetery plan."

--Eugene J. Johnson, "What Remains of Man--Aldo Rossi's Modena Cemetery" (1982).

life and death axes

1996.09.01

...an analysis and comparison between the long sacred axis and the Hadrian tomb axis. The main point being the contrast between the nympheums at the ends of the long axis and the tombs situated at the ends of the Hadrian axis. In simple terms the first axis celebrates life (nympheums) while the second (cross) axis celebrates death (tombs). This all still goes with the notion of these axes being of a scared nature, and, furthermore, it is significant that the life and death axes cross each other at right angles.

Tafuri text

1996.09.02

Exhibit 1 text

1997.03.20

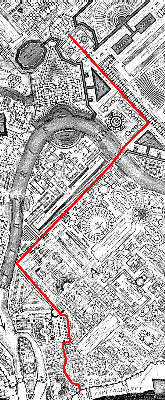

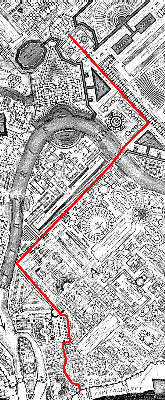

Life and Death within Piranesi's Ichnographia of the Campo Marzio

With a consistent dashed line, Piranesi demarcates the Triumphal Way through the Campo Marzio. The processional route begins, with historical and archeological accuracy, at the Templum Jani, which is situated at the bottom of the Ichnographia. The victor's march weaves through Rome's "theater district"--past small baths, shops, and brothels--and then continues on a long straight course towards the Tiber. Across the river, the procession turns behind the Sepulchrum Hadriani and approaches its end at the Templum Martis, the god of War and for whom the Campo Marzio is named. As the ultimate destination of the Triumphal Way, the Templum Martis is clearly among the most sacred, if not the most sacred, of places within the Campo Marzio, and, therefore, perhaps offers a key that lifts the Campo Marzio's "mask."

The Templum Martis fittingly promulgates overt manliness. Male genitalia boldly inform the Temple's plan, and the linear projection of the Temple's "endowment" manifests the Campo Marzio's longest straight axis.

As the axis of Mars spans from the Vatican Hill to the bend in the Tiber, it intersects the Campo Marzio's second longest straight axis, which bisects Hadrian's Tomb and the Bustum Hadriani. The perpendicular crossing of the two axes naturally creates a diametrical opposition. Geometry alone, however, does not represent the depth of their oppositeness.

The axis of Mars terminates at either end with a nymphaeum, while the axis through the Bustum Hadriani terminates at either end with an Imperial Tomb. The antithesis of nymphaeums and tombs is self-evident, and, therefore, attests to the axis of Mars representing life and the Bustum axis representing death.

The Bustum Hadriani with its crematoriums and funereal banqueting halls, moreover, is nothing less that a gigantic "machine" to facilitate the passage from this life to the next. Yet, for all its architectural bombast, the Bustum Hadriani can in no way compete with the exalted simplicity of the tiny unnamed structure, which is behind the nymphaeum on the bank of the Tiber and at the very tip of the axis of life.

|