| |

Hadrian, Hadrian's Villa, (Tivoli: AD 118-125).

Hadrian here beguiled the time in the recollections of his Odysseus-like travels, for this villa built according to his own designs, was the copy and the reflection of the most beautiful things which he had admired in the world. The names of buildings in Athens were given to special parts of the villa. The Lyceum, the Academy, the Prytanetim, the Poecile, even the vale of Tempe with the Peneus flowing through it, and indeed Elysium and Tartarus were all there.

One part was consecrated to the wonders of the Nile, and was called Canopus after the enchanting pleasure grounds of the Alexandrians. Here stood a copy of the famous temple of Serapis, which stood on a canal, and was approached by boat. Hadrian had transplanted Egypt itself to his villa. Sphinxes and statues of gods carved out of black marble and red granite surrounded the god Antinous, who was represented as Osiris in shining white marble. The temples built in Egyptian style were covered with hieroglyphics.

At a sign from the emperor these groves, valleys, and halls would become alive with the mythology of Olympus; processions of priests would make pilgrimages to Canopus, Tartarus and Elysium would become peopled with shades from Homer, swarms of bacchantes might wander through the vale of Tempe, choruses of Euripides might be heard in the Greek theatre, and in a sham fight the fleets would repeat the battle of Xerxes

Ferdinand Gregorovius (Mary E. Robinson, trans.),The Emperor Hadrian, A Picture of the Greco-Roman World in his Time (London: Macmillan and Co., 1898).

But the villa at Tivoli stands out above everything that Hadrian created, and unlike anything else in the world, forms his most splendid monument. It cast into the shade Nero's golden house. The ruins of this Sans Souci of an imperial enthusiast for art, cover even now an area of about ten miles, and present the appearance of a labyrinth of decaying royal splendour. Hadrian began to build his villa , early in his reign, and went on with it until his death.

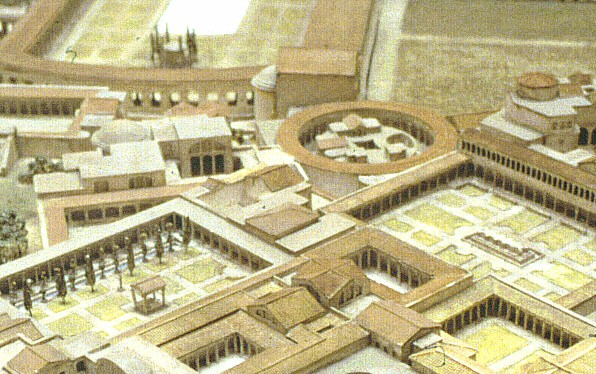

It may be doubted whether the site he selected was happily chosen. The villas of the Romans at Tusculum and Frascati, and by the falls of the Anio at Tibur, were all more open and more pleasantly situated than this villa of Hadrian; but he required a large space. It stood on a gentle elevation well below Tibur, where the view on the one side was limited by high mountains, but on the other side extended to Rome and its majestic Campagna, as far as the sea. The landscape was watered by two streams, and close by, the Anio afforded an abundant supply of water. From the Lucanian bridge near which it is conjectured was the main entrance to the villa, were to be seen for miles the wonderful pleasure-grounds stretching over hill and dale. The villa was as large as a city, and contained everything that makes a city beautiful and gay; the ordinary and commonplace alone were not to be found there. Gardens, fountains, groves, colonnades, shady corridors and cool domes, baths and lakes, basilicas, libraries, theatres, circuses, and temples of the gods shining with precious marble and, filled with works of art, were all gathered together round this imperial palace.

The large household, the stewards with their bands of slaves, the bodyguards, the swarms of artists, singers and players, the courtesans and ladies of distinction, the priests of the temple, the men of science and poets, the friends and guests of Hadrian; these all composed the inhabitants of the villa, and this crowd of courtiers, idlers, and slaves had no other object but to cheer one single man who was weary of the world, to dispel his ennui by feasts of Dionysus, and to delude him into thinking that each day was an Olympian festival. Hadrian here beguiled the time in the recollections of his Odysseus-like travels, for this villa built according to his own designs, was the copy and the reflection of the most beautiful things which he had admired in the world. The names of buildings in Athens were given to special parts of the villa. The Lyceum, the Academy, the Prytanetim, the Poecile, even the vale of Tempe with the Peneus flowing through it, and indeed Elysium and Tartarus were all there.

One part was consecrated to the wonders of the Nile, and was called Canopus after the enchanting pleasure grounds of the Alexandrians. Here stood a copy of the famous temple of Serapis, which stood on a canal, and was approached by boat. The inauguration of a worship of his Antinous, which Hadrian did not attempt in Rome, he achieved at his villa. The most beautiful statues of Antinous come from a temple in the villa. An obelisk only twenty-seven feet in height, did honour in a hieroglyphic inscription to the "Osirian Antinous, the speaker of truth, the embodied son of beauty." He was depicted upon it as offering a sacrifice to the god Ammon Ra. If the empress Sabina survived the erection of the obelisk, she must have reddened with anger at the inscription, which declared that the emperor had erected this pious monument in conjunction with his wife, the great queen and sovereign of Egypt, to whom Antinous was dear. It may be supposed that the worship of Antinous increased the influence of Egypt upon Roman art. It had long been the fashion to decorate houses and villas with scenes from the Nile, and with pictures of the animals and customs of Egypt. The wall-paintings of Pompeii and many mosaics, like the famous mosaic of Palestrina, and the mosaic in the Kircher Museum are sufficient to prove this. But Hadrian had transplanted Egypt itself to his villa. Sphinxes and statues of gods carved out of black marble and red granite surrounded the god Antinous, who was represented as Osiris in shining white marble. The temples built in Egyptian style were covered with hieroglyphics.

At a sign from the emperor these groves, valleys, and halls would become alive with the mythology of Olympus; processions of priests would make pilgrimages to Canopus, Tartarus and Elysium would become peopled with shades from Homer, swarms of bacchantes might wander through the vale of Tempe, choruses of Euripides might be heard in the Greek theatre, and in a sham fight the fleets would repeat the battle of Xerxes. But was all this anything more than a miserable pretence in comparison with the fulness and majesty of the real world through which Hadrian had travelled? The emperor would after all have surrendered all these splendid stage scenes for one drop from the rushing stream of real life, for one moment on board his gala boat on the Nile, or on the Acropolis at Athens, in Ilium, Smyrna and Damascus, amid the acclamations of his devoted people. Epictetus would have laughed to see the emperor amusing himself with a collection of the wonders of the world, and would have called it sentimentality; and perhaps Hadrian's famous villa is an evidence of the degradation of the taste of the time.

Its extent was too great to be a Tusculum of the Muses; nor was it adapted to serve as a romantic hermitage, or as a place for repose. A Roman emperor of this period could not be content unless he was in the midst of splendour on great scale. Hadrian might have written over the portal of his villa, magna domus parva quies. If the villa at Tivoli shows the strength of the impression made by the Greek world on the imperial traveller, its incredible extravagance can only be explained by his mania for building. Country seats are the least famous buildings of princes, for they serve only their own fleeting pleasure, but a ruler like Hadrian, who had provided the cities of his empire with so many public works, may be more easily forgiven than a Louis XIV, if for once he thought of himself.

We do not know how often he stayed at the villa; it was his favourite resort in his later years, and it was there that he dictated his memoirs to Phlegon. He possessed other beautiful country-houses at Praeneste and Antium. He died at Baiae, not in his villa at Tivoli. After his time the villa was more and more rarely inhabited by the emperors, until it suffered the fate of all country seats. Constantine was doubtless the first to plunder it, in order to carry off its marbles and works of art to Byzantium, At the time of the Gothic wars it existed only as a desolate world of wonders; the warriors of Belisarius were the first to encamp in it, and then those of Totila. Its ruins in the Middle Ages were called Ancient Tivoli. Its columns and blocks of marble had been stolen, its statues burnt to powder. But many things remained hidden amid the protecting rubbish, over which olives and vines had been planted. The recollection that this charming wilderness of ruins had once been a pleasure resort of Hadrian, lasted a long time. Many years before excavations were begun there, the intellectual Pope Pius II visted these ruins, and described them in melancholy words, which we may quote.

"About three miles outside Tivoli the Emperor Hadrian built a splendid villa for himself, as large as a city. Lofty and spacious arches of temples are still to be seen, half ruined courts and rooms, and remains of prodigious halls, and of fish ponds and fountains, which were supplied with water by the Anio, to cool the heat of summer. Time has disfigured everything. The walls are now covered with ivy instead of

paintings and gold embroidered tapestry. Brambles and thorns grow in the seats of the men clad in togas of purple, and serpents make their home in the bed chamber of the empress. So perishes everything earthly in the stream of time."

Antiquities were first looked for in the villa at Tivoli in the time of Alexander VI, when statues of the Muses and of Mnemosyne were found. In the sixteenth century Piero Ligorio first made a plan of the villa, then it was described by Re, and after 1735 those excavations were undertaken which have brought so much sculpture to light. Piranesi made his great plan of the villa. In the year 1871, the Italian government took possession of it, and the excavations were carried on, but they had no great result, for everything of importance had been discovered in the eighteenth century. The villa had been so completely ransacked at that time, that there was scarcely anything left of its enormous supply of marbles. Here and there floors of mosaic are to be seen; the best preserved consist of small white stones with designs in black. The extent of mosaic flooring alone has been estimated at 5000 square miles, while the astonishing variety of decorations on the pillars, pilasters, niches, and walls is a brilliant testimony to the development of art at that time.

The grounds of the villa now consist of a mass of ruins, large and small. Remains of temples, which, according to fancy, are called after Apollo, Bacchus, Serapis, Pluto, etc., of basilicas, baths, and theaters are scattered within the spacious enclosure.

The use of some of the buildings is still apparent, the long rows called cento camerelle indicating the quarter of the imperial guards, which could contain 3000 men; the high walls of a magnificent porticus are taken to be the Poecile. The Canopus looks now like a green valley, where at the end are ruins from the temple of Serapis, and the vale of Tempe can be distinguished as a deep depression, bordered by the mountains of Tivoli. The scenery of the so-called Greek theatre was still so well preserved, that in the time of Winckelmann, when the Dionysus theatre in Athens was still in ruins, it gave the best idea of an ancient theatre.

The original use of many of the other buildings and ruins is obscure, and the attempt is vain to form a whole from these fragments of the fairyland, whose central point must have been the palace of the emperor.

Ferdinand Gregorovius (Mary E. Robinson, trans.),The Emperor Hadrian, A Picture of the Greco-Roman World in his Time (London: Macmillan and Co., 1898).

| |

It is exactly the notion of creating an environment to mimic an actual "other" place--the notion of simulacra--that relates Hadrian's villa at Tivoli to today's idea of virtual reality. Far from being a mere imitation or sham, however, the villa is firmly the prototype of "virtual place." Although now largely in ruins, Hadrian's Villa was, in fact, a veritable "museum of virtual places," and, because of the high architectural quality of its many built allusions, it coincidentally functioned as a museum of Roman architecture as well.

Not only did this 2nd Century imperial palace/resort literally set the stage for "virtual experience," its example perseveres by shining new light on the contemporary concepts of virtual reality and virtual architecture, and, in spite of Hadrian's vast architectural legacy, it is a surprise, nonetheless, that his villa can still effect a viable grounding for the new virtual form of creativity that is dawning with the 21st Century.

seeking precedents... ...finding inspiration

What is Hadrian's Villa (AD 118-25) if not an architectural theme park?

3770g

|