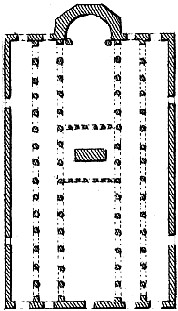

Plan of the ancient Cathedral of Ravenna, one of the most beautiful of the ancient Christian monuments, and which preserved at the same time the greatest remains of pagan antiquity. Its five aisles, divided by four ranges of columns, presented all the majesty of the ancient temples. The semicircle at the end recalled the tribunal of the ancient basilicas; and in the enclosure formed by the small columns in the centre of the nave was the choir, which, according to the rites of the primitive church, occupied this portion of the building, as we see in the Church of St. Clement, Rome. Vide 16. The Cathedral of Ravenna was often used as a basilica, in the true and ancient acceptation of the word; that is, a tribunal where justice was administered in the name of the sovereign. Under the pontificate of Clement VII judgment was here pronounced, on a difference which had arisen between this pope and Alphonso, duke of Ferrara, the decision of which having been referred to Charles V, he named the Podesta of Ravenna. Unfortunately for art, this edifice was demolished and entirely rebuilt from 1734 to 1745, from the designs of the architect Buonamici de Rimini; and the only proofs we have of its ancient splendor are those preserved by himself in the description which he published of the new cathedral.

Seroux

| |

In the summer of A.D. 390 information was brought to Milan of a serious riot at Thessalonica. In this 'large and populous' Macedonian city--which before the foundation of Constantinople appears even to have been thought of as the possible capital of the world--there had for some while been discontent on account of the quartering therein of a considerable body of barbarian troops. A comparatively trifling incident brought this bad feeling to a head. The commandant of the town--a Teuton named Botheric--had imprisoned a popular charioteer for gross immorality, and, when the people clamoured for his release in order that he might take part in the approaching circus-games, sternly refused to set him free. Thereupon the mob, furious at being balked of its pleasure by one of the hated barbarians, broke out into a riot, savagely murdered Botheric, and dragged his body through the streets.

Infuriated by this outrage, Theodosius determined to take fearful vengeance. His intention was known, and Ambrose, notwithstanding the fact that he was not a persona grata at Court, felt in duty bound to interpose. He had several interviews with the Emperor, in the course of which he became acquainted with his plan for punishing the city. This he condemned as most atrocious'. Eventually he appears to have received some vague assurance that it should not be carried out. But, behind his back, the courtiers who were hostile to him--perhaps led by the unscrupulous Master of the Offices, Rufinus--inflamed the Emperor's passion, representing that it would be fatal policy to neglect to visit such a crime with exemplary chastisement. By their 'clamour' Theodosius was persuaded to issue a secret order for a massacre of the inhabitants of Thessalonica up to a stated number. Soon afterwards he repented his cruelty, and countermanded the order. But the reprieve arrived too late.

The people of Thessalonica were invited to attend a grand exhibition in the Circus. Not suspecting any treachery, a great multitude assembled, and speedily became absorbed in contemplation of the games. Suddenly, at a given signal, the soldiers rushed in, and began to slaughters No distinction was made between the guilty and the innocent, or between native inhabitants and strangers: all alike were cut down, 'as ears of corn in the time of harvest'. The butchery lasted for three hours, and at least 7,000 persons perished. Many pathetic incidents occurred. One devoted slave offered his own life for that of his master. A wealthy merchant tried to bribe the soldiers to kill him in the place of his two sons. They dared not spare both the boys, but agreed to allow the father to substitute himself for one of them. But when asked to point out which of the two he wished to save, the agonized parent found himself unable to make the decision. At last the executioners, losing patience, slew both sons before his eyes.

When Ambrose heard of the massacre, he was presiding over a Council of Italian and Gallican bishops, summoned to consider the question of communion with Felix of Trier. He was profoundly shocked and horrified, as were all the assembled prelates. Theodosius had indeed exceeded even that liberal allowance of violence and crime which was deemed permissible for a Roman Emperor. So gross an offence could not possibly be overlooked; the only point for consideration was what action should be taken against the offender. But to determine a matter of such crucial importance time was needed; and Ambrose wisely refrained from proceeding precipitately. Fortunately, when the news of the atrocity reached Milan, Theodosius was absent at Verona, where he was in residence between the 18th of August and the 8th of September. A few days before the return of the Court, Ambrose, who had not yet finally settled what it was proper for him to do, and was therefore not yet prepared to face the Emperor, himself quitted Milan, and on the pretext of sickness and the need of change of air--indeed he really was ill--withdrew into the country.

He was now approaching a decision, and he honestly believed that he was being divinely led thereto. On the night before he left Milan he dreamt that he was saying Mass in the cathedral, and that Theodosius came in, and that thereafter he found himself powerless to offer the Sacrifice. This providential warning appeared to be confirmed by a 'heavenly sign'--that is, by a comet which (as is now known) was visible from the 22nd of August to the 17th of September in this year. Further, the prelates attending the Council had indicated clearly their opinion that the Bishop of the capital could not evade the distressing duty of forcing the Emperor to realize the heinousness of his sin and his need of being reconciled to God. Thus Ambrose gradually made up his mind. He would excommunicate Theodosius. He would do so in as gentle a manner as was possible under the circumstances; he would concede as much as he dared in order to minimize the public scandal. But the guilty monarch must be excluded from 'the assembly of the Church and participation in the sacraments' until he should have acknowledged his sin and done fitting penance.

From his unknown rural retreat, probably about the 10th of September, Ambrose wrote with his own hand a very secret letter, which was intended for the eye of the Emperor alone. This confidential document, announcing the excommunication, is a veritable masterpiece of delicate tact, which historians of every age and school--with the striking exception of Gibbon--unanimously admire.

'I bear an affectionate and grateful memory of your former friendship towards me, and of your great condescension in so often granting favours to others at my request. You may be sure, then, that it was not ingratitude which induced me to avoid your presence, which hitherto I have ever sought with the greatest eagerness. I will briefly explain my reasons for so doing.

'I found that I alone of all your Court was denied the right of hearing what was going on, that I might also be deprived of the privilege of speaking; for you were frequently annoyed at my having received intelligence of decisions taken in your Consistory. Wherefore I modestly did my best to conform to your imperial will. I tried to spare you annoyance by endeavouring that no information concerning the imperial decisions should reach me. But I could not close my ears with wax, as men did in the old stories; nor, when I did hear, could I be silent. That would be the most miserable thing of all-to have one's conscience bound and one's lips closed. As the Scriptures tell us, if the priest warn not the sinner, the sinner shall die in his sin, and the priest also shall be punished, because he did not warn him.

'Listen, August Emperor. You have zeal for the faith, I own it; you have fear of God, I confess it. But you have a vehemence of temper, which, if soothed, may speedily be changed into compassion, but which, if inflamed, becomes so violent that you can scarcely restrain it. I would to God that those about you, even if they do not moderate it, would at least refrain from stimulating it! This vehemence I have preferred secretly to commend to your consideration rather than run the risk of stirring it up by a public act. So I have preferred to seem somewhat slack in the discharge of my duty rather than lacking in respect to my sovereign; and that others should blame me for failure to exercise my priestly power rather than that you should consider me, whom am most loyal to you, deficient in reverence. This I have done that you might be free to choose for yourself in calmness the course which you ought to follow.

'A deed has been perpetrated at Thessalonica, which has no parallel in history; a deed which I in vain attempted to prevent; a deed which, in the frequent expostulations which I addressed to you beforehand, I declared would be most atrocious; a deed which you yourself, by your later attempt to cancel it, have confessed to be heinous. This deed I could not extenuate. When the news of it first came, a Council was in session on account of the arrival of bishops from Gaul. All the assembled bishops deplored it; not a single one viewed it indulgently. Your act could not be forgiven even if you remained in the communion of Ambrose; on the contrary the odium of the crime would fall even more heavily on me, if I were not to declare to you the necessity of becoming reconciled to our God.

'Are you ashamed, Sir, to do as did David, who was a prophet as well as a king, and an ancestor of Christ according to the flesh? He, when he had listened to the parable of the poor man's ewe lamb, recognized that he himself was condemned by it and cried, I have sinned against the Lord. Do not, Sir, take it ill if the same words are addressed to you which the prophet addressed to David--Thou art the man. For if you give careful heed to them, and answer, I have sinned against the Lord, then to you also shall it be said, Because thou repentest, the Lord hath put away thy sin.

'This I have written, not to confound you, but to induce you, by quoting a royal precedent, to put away this sin from your kingdom. You may do that by humbling your soul before God. You are a man, and temptation has come to you; now get the better of it. Tears and penitence alone can take away sin. Neither angel nor archangel can do it. Nay, the Lord Himself grants no remission of sin except to the penitent.

'I advise, I entreat, I exhort, I admonish. It grieves me that you, who were an example of singular piety, who exercised consummate clemency, who would not suffer individual offenders to be placed in jeopardy, should not mourn over the destruction of so many innocent persons. Successful as you have been in war, and worthy of praise in other respects, yet piety has ever been the crown of your achievements. The devil has grudged you your chief excellence-overcome him, while you have the means. Add not sin to sin by following a course which has proved the ruin of many.

'For my part, debtor as I am to your goodness in all other things, grateful as I must ever be for it--for your goodness has surpassed that of many emperors, and indeed has been equalled only by one--for my part, I say, though I have no ground for supposing that you will show yourself contumacious, still I am not free from apprehension. I dare not offer the Sacrifice, if you determine to attend. For can it possibly be right, after the slaughter of so many, to do that which may not be done after the blood of only one innocent person has been shed? I trow not!

'I write with my own hand what I wish to be read by yourself alone. Doubtless you desire to be approved by God. You shall make your oblation when you have been given liberty to sacrifice, when your offering will be acceptable to God. Would it not be a delight to me to enjoy the Emperor's favour, and do as he would have me, if the case allowed it? Yet prayer, by itself, is a sacrifice. Prayer obtains pardon, because it indicates humility; but the offering would imply contempt, and would accordingly be rejected. For God Himself assures us that he prefers the keeping of His commandment to sacrifice. Do, therefore, that which you know to be better for the time.

'You have my love, my affection, my prayers. If you believe that, follow my instructions; if you believe it, acknowledge the truth of what I say; but if you believe it not, at least pardon me for preferring God to my sovereign. August Emperor, may you and your Sacred Offspring enjoy in the greatest happiness and prosperity perpetual peace!'

This admirable letter, expressing the writer's profound respect for Theodosius, his appreciation of his fine qualities, and his anxiety to treat him with the greatest possible consideration, but at the same time announcing his unalterable determination to deprive him of communion until he should have done penance, was well calculated to appeal to the Emperor's better nature. Yet Ambrose (as is shown by the letter itself) was apprehensive as to the attitude which the Emperor would adopt. Would he submit to episcopal authority or would he resist? Would he listen to Ambrose, or would he allow himself once more to be influenced by Rufinus and the Court opposition to the Bishop?

Strangely enough, we do not know precisely what did happen. Paulinus reports a short dialogue between Theodosius and Ambrose, wherein the former pleaded that King David had sinned even worse than himself, since he had been guilty of adultery as well as murder, and the latter had retorted, 'You have imitated his crime; imitate his amendment.' But Paulinus does not specify the circumstances of this conversation; and the words which he puts in the mouth of the Bishop are taken from one of Ambrose's published works. Sozomen, again, makes the statement that 'Ambrose excluded the Emperor from the church and excommunicated him', and further relates-for the first time-the well-known story of the Emperor's personal encounter with the Bishop. According to this narrative, Theodosius, notwithstanding the excommunication, went to the church to pray. Ambrose met him before the doors, and, laying hold of his purple robe, publicly forbade him to enter. 'Stand back!' he said. 'A man defiled by sin and with hands stained with innocent blood has no right, without repentance, to enter these sacred precincts or participate in the Divine Mysteries.' The Emperor admired the boldness of the Bishop, and retraced his steps, stricken with penitence. But this story is plainly improbable

It is not likely that Theodosius, knowing Ambrose's resolute nature, would have taken the risk of defying him publicly; nor is it likely that Ambrose, if he had actually been so defied, would have done more than simply decline to offer the Sacrifice in the imperial presence. The account, indeed, appears to be mainly a dramatic amplification of the statement that 'Ambrose excluded the Emperor from the church', by a writer whose object was to emphasize the idea of the subordination of the civil to the ecclesiastical power. But the story was adopted, and rhetorically elaborated, by Theodoret, and through him passed into the narratives of later ecclesiastical historians.

The encounter in the atrium may be dismissed as legendary. Yet the evidence of Paulinus and Sozomen (though unreliable as regards details) seems to point to a definite fact-that Theodosius, for some while, resisted the authority of the Bishop and refused to submit to the humiliation of public penance.

How was his ultimate surrender brought about? Until comparatively recently historians have credited and repeated the following detailed, but largely imaginary, recital of the disingenuous Theodoret.

When Christmas approached, the excommunicated Emperor shut himself up in his palace, in a state of extreme dejection. One day Rufinus, entering suddenly, found him in tears and ventured to inquire the reason of his grief. The Emperor answered, groaning, 'You can be cheerful, Rufinus, but I must be sad. God's temple is open to slaves and beggars, who may go in freely and pray to their Lord. But to me its gate is closed, and so must be also the gate of heaven. For I cannot forget the words of our Lord, Whatsoever ye shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven.' Rufinus said, 'Give me permission, and I will hasten to the Bishop and by my entreaties prevail on him to loosen your bonds.' 'You will not persuade him', Theodosius replied. 'I see the justice of his sentence; he will never transgress the law of God through fear of the Emperor's power.' The minister, however, was so sure of success that at last the despairing monarch began to entertain a little hope. It was agreed that Rufinus should go to the Bishop at once, and that Theodosius should follow after a short interval. The Master of the Offices then called on Ambrose. When the latter saw him, he said, 'You are as shameless as a dog, Rufinus. It was you who advised that abominable massacre, and now you come here without shame or fear for the outrage you have perpetrated on men made in God's image.' Rufinus cringed, but intimated that the Emperor himself was on the way. 'I give you notice', said Ambrose, 'that I will not allow him to enter the atrium of the church. If he chooses to play the tyrant, I will gladly let myself be put to death.' Seeing that the Bishop was inflexible, Rufinus sent a message to the Emperor, advising him not to leave the palace. But Theodosius had already started, and, when the message was delivered, had reached the Forum. Notwithstanding the warning he pursued his way to the basilica, exclaiming, 'I will go and receive the censure which I deserve.' He did not attempt to enter the church itself, but proceeded to the sacristy, where Ambrose, attended by his presbyters, was sitting to receive the salutations of the faithful. Here he presented himself and asked to be given absolution. At first Ambrose misunderstood the spirit in which he had come, and fiercely taxed him with attempting to extort by force a concession which was contrary to the Law of God. Theodosius, however, disabused him of this error, and, humbly acknowledging his crime, asked that 'remedies' might be prescribed whereby his soul might be healed of its wound. Ambrose then dictated his terms. First, as a precaution against reckless punishments decreed under the influence of passion, he required that the Emperor should enact a law providing that all sentences of death or proscription should be suspended for thirty days and then submitted for reconsideration; secondly, he insisted that the Emperor should do penance. Both these conditions were accepted.

Most modern critics are agreed that Theodoret's narrative is, at any rate in the main, a clumsy invention, designed to magnify the humiliation of the Emperor and the triumph of the Bishop. Both the words and acts attributed to the chief personages in the drama are fantastically destitute of the element of probability. In this unveracious narrative, however, there are certain details which do not seem to be pure invention and may have been derived by Theodoret from some trustworthy, but unknown, source. These are the intervention of Rufinus, the attempt to effect a reconciliation between the Emperor and the Bishop, and the connection of the Emperor's readmission to communion with the Christmas festival. Further, the law suspending the execution of condemned criminals for thirty days is mentioned by Rufinus and Sozomen and found in the Code; but Theodoret is wrong in stating that Ambrose dictated it to Theodosius as a condition of absolution, since it is now practically certain that the correct date of the edict is the 18th of August, A.D. 390. In other words, the law was issued by Theodosius at Verona, under the influence of remorse for his savage order about the massacre, but more than two months before the formal penance took place.

One may conjecture what occurred. Ambrose a pears to have sent his letter to Theodosius about the 10th of September. After an interval he returned to Milan. The Emperor made no reply to the letter, and at first ignored the Bishop, though he did not venture to risk a public scandal by presenting himself in the cathedral. The situation, however, was intolerable; moreover Theodosius, with all his faults, was a religious man and he could not rest easy under the ban of the Church. In October, therefore, he authorized Rufinus, the Master of the Offices--a man skilled in the arrangement of delicate affairs--to negotiate a compromise with the Bishop. It is possible that it was in the course of the ensuing conversations that the argument about King David, referred to by Paulinus, was put forward (at the Emperor's suggestion) by Rufinus, and Ambrose sent back the message, 'You have imitated his crime, imitate his amendment.' In any case the negotiations came to nothing. Ambrose would not agree to any compromise, would not be satisfied with any thing less than a public penance. The Emperor, realizing that the Bishop was determined on the point and doubtless acknowledging in his heart that he was in the right, at last--perhaps about the end of October--consented to do what was required of him.

In consideration of the exceptional humiliation which penance entailed on a person of his exalted rank, and of the real remorse which he had felt for his passionate crime-remorse proved by the promulgation of the law of the 18th of August, which was calculated to prevent such crimes in future--the period of penance was shortened to a few weeks. During these weeks the Emperor was allowed to be present at the Sacred Mysteries, according to the custom of the Milanese Church, but did not communicate; he laid aside his imperial ornaments as a sign of mourning, and publicly in the church--in the presence of his wondering subjects who prayed and wept with him--entreated pardon for his sin. His solemn readmission to communion took place at Christmas.

The story of the penance of Theodosius is honourable to each of the principal personages concerned. The action of Ambrose was no mere arrogant display of sacerdotal authority, but a highly necessary vindication of the sanctity of Divine laws against one who had offended grievously both against God and against humanity. On the other hand, the action of Theodosius was no weak and craven concession to the power of an encroaching hierarchy, but a magnanimous recognition of the Church's right to preserve the fundamental principles of religion and morality from violation. The incident marks a turning-point in the history of the Church. For the first time we find a minister of the Gospel claiming power to judge, condemn, punish, and finally pardon princes; and for the first time we find a monarch humbly submitting to a spiritual authority which he recognized and publicly acknowledged to be higher than his own. Here is the beginning of a new relationship between Church and State. Further, the incident marks a turning-point in the personal relations between Theodosius and Ambrose. Formerly, as has been shown, the Emperor, accustomed to the subservience of the bishops of the East, was offended by the independent bearing of the great Bishop of Milan, resented his interference in matters which seemed to be outside his proper province, and even endeavoured to keep him in ignorance of the deliberations of the Consistory on imperial affairs. In A.D. 390, however, he came to understand the real greatness of the man whom he had been disposed to regard as an impertinent meddler. Henceforth he adopted a new attitude towards him; and, though he never so absolutely subjected himself to his influence as has sometimes been supposed, he took him fully into his confidence, and in his later ecclesiastical policy--particularly in the legislation against pagans and heretics--was almost certainly guided to a considerable extent by his advice.

A striking incident, illustrative of the relations between Ambrose and the Emperor, is related by Theodoret as having occurred very soon after the conclusion of the famous penance, though it may more probably be assigned to the time when Theodosius first took up his residence at Milan after the defeat of Maximus. On some great festival the Emperor attended Mass in the cathedral. At the point in the service when the faithful advanced to the altar to make their offerings of bread and wine, he went up and presented his offering, and then remained among the clergy within the sanctuary to receive the communion. This was in accordance with Constantinopolitan custom; at Milan, however, it was usual for the emperors to take their place, not within the sanctuary, but at the head of the congregation. Ambrose, observing that Theodosius did not retire, sent to inquire what he wanted, and, being told that he was waiting to communicate, bade the archdeacon say to him, 'The priests alone, Sir, are allowed to remain within the sanctuary. Depart, therefore, and stand with the rest of the laity. The purple makes princes, not priests.' The Emperor obeyed--though not, perhaps, with that exaggerated humility which the Greek historian attributes to him. He could hardly refuse to conform to a usage which had been observed by earlier Western emperors and which he himself recognized as more seemly. He did not, however, resent--as he might well have done--the action of Ambrose on this occasion; on the contrary, he admired him for it. 'I know no one except Ambrose', he is reported to have said, 'who deserves the name of bishop.'

F. Homes Dudden, The Life and Times of St. Ambrose (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935), pp. 381-92.

| |

|