Form 000 2300

Form 001 2301

Ur-Ottopia House 2303

Maison Millennium 001 2304

Palace of Ottopia 2305

Haus der Kunst 2306

Schizophrenic Folds 2307

Infringement Complex 2308

House for Otto 3 2309

House for Otto 4 2310

House for Otto 5 2311

House for Otto 6 2312

House for Otto 7 2313

House for Otto 8 2314

House for Otto 9 2315

House for Otto 10 2316

Maison Millennium 002 2317

Maison Millennium 003 2318

Maison Millennium 004 2319

| |

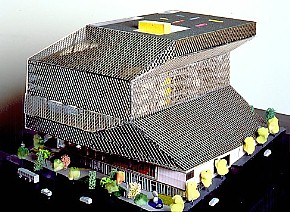

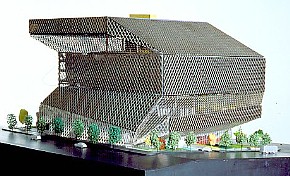

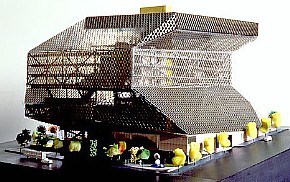

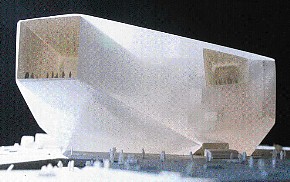

OMA, Seattle Public Library (Seattle, WA: 1999-2004).

6 June 1999

PRESS RELEASE

OMA DESIGNS CASA DA MUSICA IN PORTO

The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) from Rotterdam was chosen to design the new Porto concert hall, the Casa da Música. The Portuguese jury announced OMA's design proposal as the winning scheme.

The competition went on between the French Architect Dominique Perrault, the American Architect Rafael Viñoly and OMA whose principal is Rem Koolhaas.

The project is part of the planning for 2001, the year that Porto together with Rotterdam will be cultural capital of Europe. In a way the Casa da Música will be a joint-venture between the two cultural cities.

The concert hall will be realized at Rotunda da Boavista, a square just outside the historical centre, in an expressive, rock like form.

The design contains two concert halls, a restaurant, a music shop, a café, a roof terrace and educational and cybermusic facilities.

The large auditorium will have a capacity of 1500 seats, some of them in boxes. The walls in front and back will be made entirely out of glass, which opens the hall towards the city. The small auditorium with 350 seats opens in the same way towards the city. The two spaces are separated by a glass wall only.

Ove Arup & Partners / Cecil Balmond will be the structural Engineers for this project, the acoustics are in hands of TNO / Renz van Luxemburg.

This is the second major project for OMA in short time, on May 26 the office got the commission to build the new Seattle Public Library.

| |

Peter Eisenman, Blurred Zones (1 February 1999).

Author unknown.

Architect Peter Eisenman who is a Visiting Professor at Yale this Spring teaching a studio with Philip Johnson, delivered his lecture "Blurred Zones" on Monday February 1. The title "Blurred Zones" expresses Eisenman's preoccupation with recent concepts: overcoming the dominance of the metaphysics of presence; unmotivating the sign and the signified and the need to change the desires of the subject.

Eisenman said that the norm is to think about architecture, "as a response to a motivation that is a desire for a place, for ground, for containment, shelter, security, imagery and for standing for something." He believes that architecture can also enrich those desires of place by looking to other issues. So with his first point, he looks to why the metaphysics of presence, making things tangible, needs to be so dominant especially with media and advertising now making the human mind and body respond to things differently. He referred to how, with the possibility of non-presence, morphing, and changing states of realities, young people have no problem with virtual time and space compared to his generation.

If this is the case, he asked "how does architecture respond? Architecture used to be the media; before the Renaissance, the Cathedrals were media." He believes that architecture has lost it's mediating function although it still affects the relationship between mind, body and eye. He noted that "Since architecture is always presence, since the virtual is part of our mental condition, our bodily responses need to function between the mental, the conceptual and the physical." He feels that at this juncture in history we need to ask what is the basis of architecture if other than the metaphysics of presence? So he suggests a "blurred zone" between presence and virtuality for architecture to sustain interest.

The second point that he raised is about becoming 'unmotivated of the sign'. He argued that "if architecture can function symbolically, as it did before media, between the presence and the virtual, there is an other motivation. We don't need architecture for information but to provide a form that we cannot get through any other media."

The third and most important condition which Eisenman presented concerns the subject. He argues that "On the one hand, if we are to deal with the dislocation of place, to unmotivate the signs, then we have to open up desire to a situation of pure desire. To move the subject from motivated to unmotivated we can then open the unconscious to the phenomenon of space and time. What architecture can do is to move from the conscious and signs to the unconscious of space and time. Then we need to change the subjects and the architects." Eisenman would want us to resist both the reductive formal motivations of the Bauhaus and the new "blobatecture" of where the computer illustrates with no knowledge of history or theory.

With this Eisenman suggests a new condition of architecture, a third text, that requires a blurring. But he says, "you have to know what it is being blurred, this requires a penetrating understanding. Historically, he stressed "architecture has constantly transformed itself and upset the normative." So he looks to absolving two texts, one of function, site and program and the second of interiority (the sign and the signified, so that the wall and the sign of the wall are always present simultaneously), and anteriority (where they are detatched). "To do this I look at the way architects such as Brunelleschi, Bramante, Loos, Mies and LeCorbusier have attempted the displacement of the sign from the signified in order to reposition the wall, column and floor." Those two texts define traditional architectural practice.

The projects that involve this blurring, are motivated towards becoming unmotivated of the first two texts. This is a diagrammatic superimposition of the third text of blurring. "I have to then unmotivate myself, which is often the hardest." He said "that is the schema for what I will show you now, but theory only takes you so far. You have to trust your intuition no matter how flawed it might be.

The first project which tests his technique of "Blurred Zones" is a proposal for a new museum in Staten Island on the Ferry Terminal. The buildingís diagram is constructed by introducing a flow of resistance's through a formal grid. Unlike the Guggenheim, its void is a part of a system of layers with no central space -- one can't move simply between outside and inside by following the forms. Borough President Molinari was enamored by the project, and the mayor wants to add a baseball stadium and turn the museum into a sports hall of fame. HOK is now the lead architect on the sports stadium and Eisenman is designing a museum project that will be located somewhere between the baseball stadium and ferry terminal.

For a mega-project, Eisenman is designing a mixed-use development that began as a stadium for the Arizona Cardinals and had to be photogenic from a blimp as well as close up for various uses. He sad that "he had to "design for luxury boxes, and a blimp shot. The rest comes out of a can. Stadiums are not like a museums, because there is an architectural type, the bowl, that you start from." The two million-square-foot convention center, 3,000-room hotel and a residential complex will support the $ 300 million stadium. A 750-by-75-foot light-weight truss supports a collapsible roof with operable garage doors. A $20 million system rolls the turf out into the sunlight so it stays green. Eisenman commented, "This is reality, and you laugh." Despite the projectís dependence on media and simulation, the $1.8 million complex might begin construction in December.

In Berlin, Eisenman revised his original plans of the Holocaust Memorial for the Murdered Jews. The first design, made in collaboration with Richard Serra, consisted of 4,500 stone pillars, 2'9" x 7'6", spaced 2'9" apart with varying heights from 15 feet to 1.5 feet. Both the politicians and the public thought it inhuman. But Eisenman noted, "the affective experience of walking in that space would be quite extraordinary; like walking through a field of wheat or corn. You could feel lost -- but that is what the public did not want. The officials desired more symbolism and for it to be understandable." The Social Democrats, new in office, requested that an archive and learning center be added. So Eisenman integrated an underground archival building with a series of tunnels, multiple entrances, and reduced the field to 2,700 pillars. He added a six level wall, 600-feet long by 60-feet high, to store one million books remaining from the murdered Jews.

With a third example Eisenman presented a competition entry for a concert hall in a public plaza in Bruges, Belgium. As a more theoretical experiment, which incorporated the acoustical requirements of the program, Eisenman developed a diagram from the morphology of the history of the cityís topography, its relationship to the water and transportation routes. He overlaid the plan of Bruges onto a conceptual grid that he derived from a deformation of contour lines. This new conceptual land formation became the concert hall. The folded surfaces of building form the lobby, and mold the main space. But, said Eisenman, the development of this Blurred Zone lost the competition because "it didn't look like a concert hall, a building or the ground. The judges wanted a design motivated by their understanding of what a concert hall should look like."

Eisenman concluded, "one never has a certainty to the reality of the possibility of building and experimentation. As I understand what I do better, I am less ideological on the theory of the third text in actual buildings. I am not as didactic and pure as my critics and historians wish me to be, or as I used to be. When you get into larger scale projects, you realize you have less control for the theory -- if you want to build." Eisenman confessed, "it is not so much fun to be ideologically pure.... One isn't influential unless one builds, 25 years ago I didn't think that way."

In a series of questions from the audience, Eisenman noted that a loss of critical content in architecture in general, has its consequences. "Am I falling into the danger zone of spectacles and might loose my criticality because of the desires of the clients? We have all become trapped through this commodification of architecture. What people see is a commodification, the question is: Is that a problem or not?"

|