| |

| |

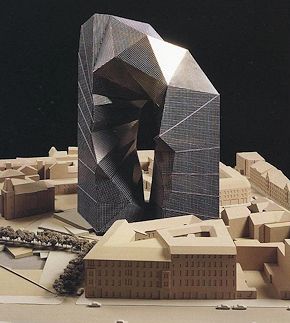

Time is more than a mysterium for architects and poets: it is indeed a sensuous and social fact, the context of con texts and imbricated with the addresser and addressee and the palpability of form. In John Hejduk's architecture, we are constantly haunted by the space that is always timely. His book Victims is nothing if not a critical encyclopaedia of the darkest event of our epoch. If Adorno asked what lyric was possible after Auschwitz, we now have our response. The appropriate response after Auschwitz is a chiliastic architecture that again and again, glaringly, audaciously, poignantly and angrily, studies last things and speaks of things that might last. This melancholy and critical architecture and poetry are healthier than the eclectic pedanticism of our day and all reductive purisms.

Hejduk's clock, like Loos's column for Chicago, functions as a kind of aphoristic manifesto. A master of uncertainty and doubt, Hejduk's architecture speaks of the provisional and not the absolute. What architect since Schwitters has made such a determined effort to fuse art and shelter. What critique is surer in its swerve away from the contemporary baroque and the deathly authoritarian symmetries of our Rationalists? In Hejduk, as in Walter Benjamin, we are given an image at once transcendental and logical. Instead of 'critical regionalism', we are reminded that the dominant region is the mind. Hejduk's works are the mature speculations of a cosmopolite in the age of the destruction of the city and one who approaches the institution of architecture with a militant intransigence.

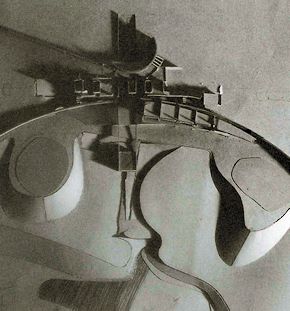

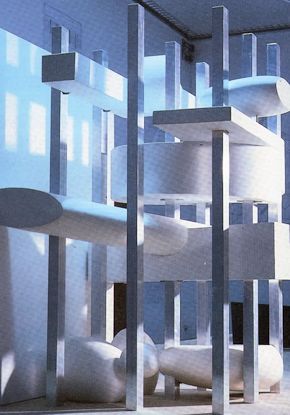

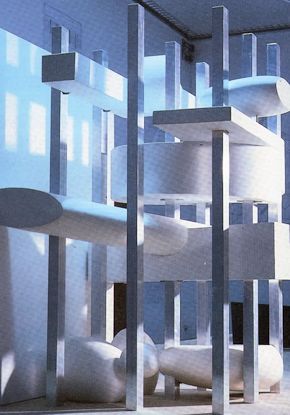

During my daily visits to The Great Hall during

the summer and later, the fall of 1987 (the structures were

fabricated in this campus space during the summer; one was

partially assembled to check for fit and then dismantled; all parts

were hauled away and stored in our sculpture studios; then all

brought back again and finally erected in the week leading to the

public opening in November), was continually amazed by our

architects and their students who were building the figures of

Object and Subject. Of course they knew they had an enormous

job on their hands against a non-negotiable deadline. But there

seemed more to it than time. Perhaps it was an awareness of

being part of something that could rightfully be termed historic:

this was the first actual building based on the architect's then

unpublished Riga book; the first of the architect's special projects

to be built in the United States; and all of this was happening in the

what had

been the

center of Haviland Hall, an early 19th century building, itself

conceived as Utopian architecture. Or perhaps it was a unique

inspiration, drawn from the privilege of intimacy, John Hejduk has

been a visiting critic in our department of architectural studies and

now,

in

turn, this small

and select community was meeting

a

colleague and mentor in his Architecture, Whichever the case,

these workers worked with an intensity and resolve that to me

bordered on the ritual act of devotion.

step-by-step documentation of the process, this book is a

these individuals and many others at The University of

the Arts and The Cooper Union, who brought Riga to life. It is

equally a tribute to the patrons

individuals, agencies, and

corporations who, through their understanding of the work's importance and faith in our purpose, contributed generous support in

In Its

tribute to

—

—

aid of this project.

One of the luxuries of producing this publication long after the

completion of the project has been the ability to gather and record

a measure of that which we, for all of our organization, could not

have anticipated the impact of Riga on audiences. Responses,

beginning with the standing-room-only crowds that turned out for

opening night and its related events, were many and significant.

Some of the more formal intellectual and artistic reflections are

here preserved, in a format that also has benefited from retrospection, and is intended to commemorate to readers the full range of

our experiences.

Finally, this book is a gift to John Hejduk for that part of his gift that

he shared with The University of the Arts and the public through

The

Riga Project.

| |

|