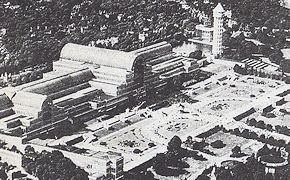

John Paxton, Reconstruction of the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, 1854.

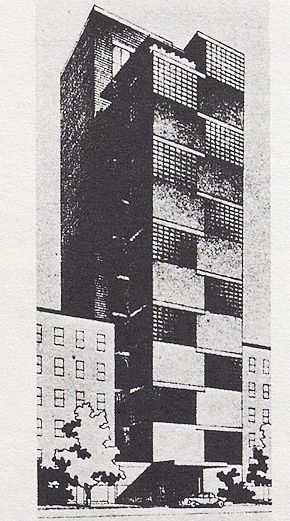

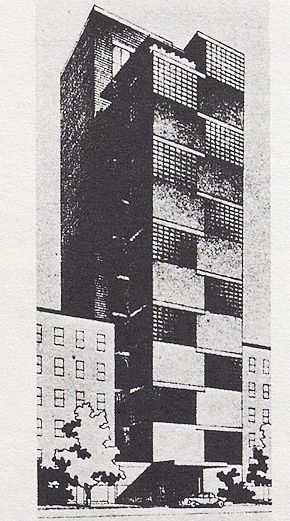

George Howe and William Lescaze, Design far the Museum of Modem Art, New York, the fifth proposal, 1930: perspective.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona Pavilion at the International Exhibition in 1928, reconstruction, Barcelona, 1986.

| |

This does not imply that typological research has outlived its usefulness.

On the contrary, it is the very breakdown of the structure of the so-called "post-industrial" metropolis which gives rise once again to the

identification and examination of the validity of every type, not according to an abstract categorization, but case by case, also overcoming

conventional comparisons and contrasts between historic centre, where total preservation and cautious restoration are expected, and the remaining territory, where innovation is considered necessary only in enclosed areas which contain what is considered to be all the new and future functions and where (now that the great exhibitions are a thing of the past) museum design tends to mean Science parks that are like cultural Disneylands.

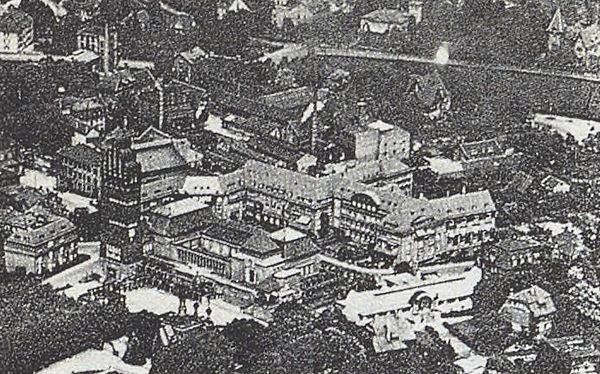

In fact I believe that the new-found organic unity of the urban structure also requires strategic and contextual choices, involving concentration or diffusion, centralization and polarization, continuity and discontinuity of functions, and the ability to reduce the traditional distinctions between city and countryside, between city centre and suburbs, between ancient and modern, between efficiency and decay. In this way the museum, like all other institutions, would be integrated into a comprehensive museum system, interacting with other functional systems (transport, culture in generai, various levels of education, leisure etc.) and would be differentiated in the typological sense in terms of its tasks and degree of productivity, hospitality, attendance, and direct operativeness, factors which these days tend to cause the museum-institution as a type to degenerate more and more. In her opening paper at that symposium Helen Searing also saw Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace, built for the 1851 World Exhibition in London, Howe and Lescaze's 1930 design for New York's Museum of

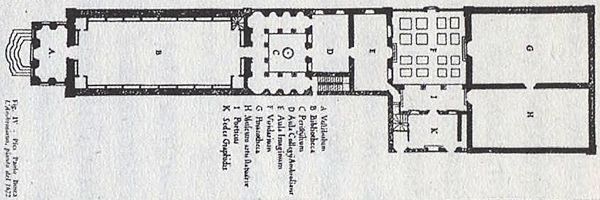

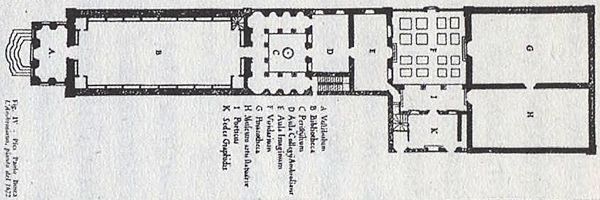

Modern Art and Mies van der Rohe's museums in generai as belonging to a well-stigmatized tradition of technological caricature. In my examination at the time, meanwhile, I cited precisely these cases not as alternative archetypes, but as types which it would almost be possible to use again (one reason being their correlative monumental value), especially if considered in the context of the complex and ramified discontinuity of a museum system. And above all, I took as an example the Ambrosiana of Milan (only Pevsner and Seling, of all the scholars I have mentioned so far, refer to it and even then only as a library). A combination of library and museum, it was founded by Federico Borromeo in the Mannerist period as a centre for promotion of culture during the Counter-Reform, to further promote the

arts. It will suffice to recall the influence it had on the realism of the so-called Seicento Lombardo and the sublime religious and popular

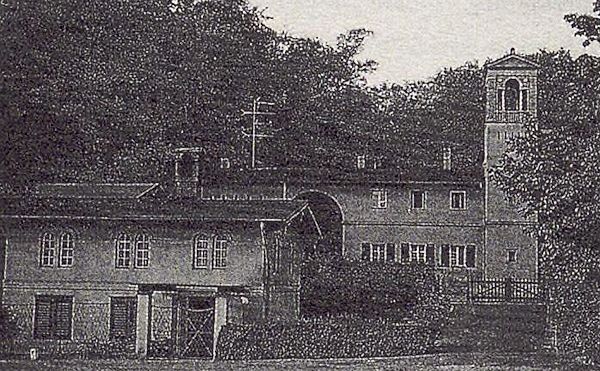

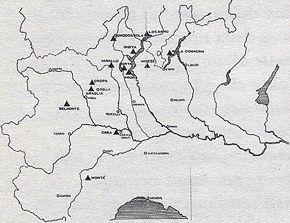

creativity throughout the Diocesi of Milan, up to the construction of the famous Sacri Monti in the border valleys, and the villas and country houses inspired by Schinkel and conceived together with his pupils in the museum-park of Glienicke as the mnemonic and interpretive synthesis of a stay in the Mediterranean. And the Kunstlerkonie founded by Ernst Ludvig at Darmstadt and opened during the 1901 exhibition. So, if we stretch the limits between current ideology and taste into a graded scale of authenticity and falsification of the forms arising out of architectural types, should we perhaps consider the share of monumentality in Schinkel's two works to be acceptable in a different way (absit inuria verbo)? And possibly even distinguish between their acceptability and that of the Danteum, which the architects Terragni and Lingeri dedicated to Rome in 1938 (year XVI of the Fascist era) on the Via dell'Impero, as an allegory of an allegorical national poem?"

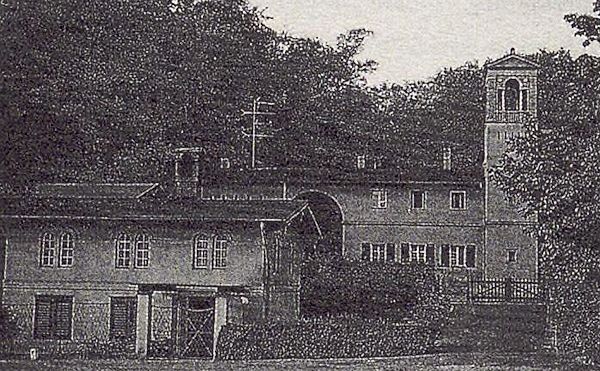

Ludwig Persius, Farmstead of Klein-Glienicke Park, Berlin, 1843-44: view.

| |

Lelio Buzzi, Ambrosiana complex, Milan, 1603-09, in the plan of 1672 by Pier Paolo Bosca, third Ambrosiana prefect.

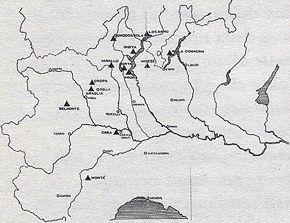

Location of the sacred mountains of Piedmont and Lombardy, from S. Lange.

| |

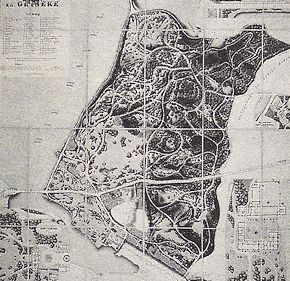

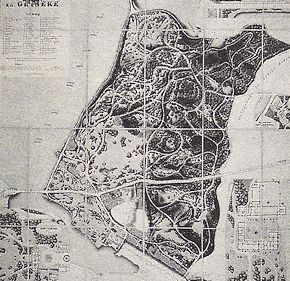

Plan of the Klein-Glienicke Park, Berlin, including the works of Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Ludwig Persius. 1862.

|

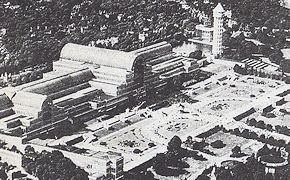

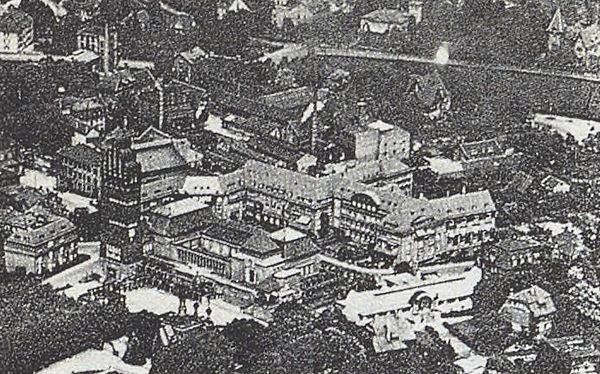

Joseph Maria Olbrich, Artists 'School on the Mathildenhˇhe, Darmstadt, 1901: birds-eye views (buildings by Behrens, Benois, Habich, Hoetger, Muller, Olbrich).

|