Quondamopolis | it was not uncommon to see mobile homes parked in front of old rural farm houses |

|

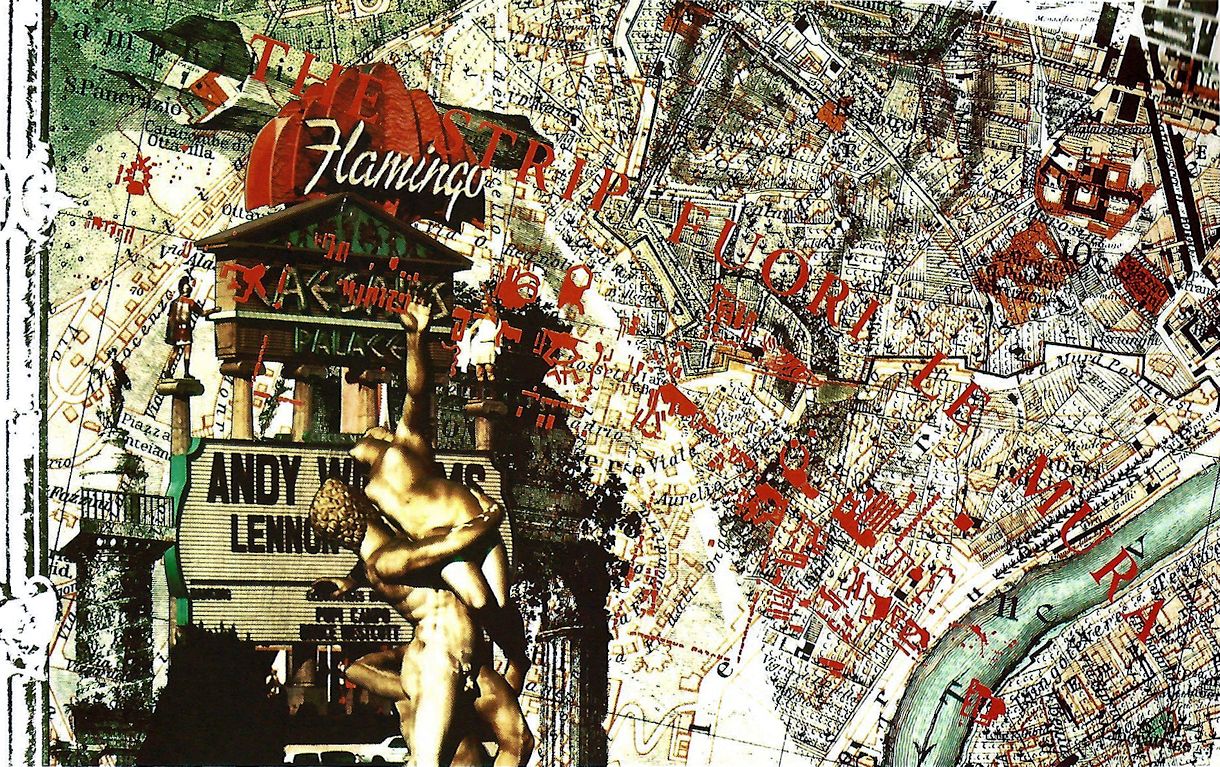

Venturi and Rauch Roma Interrotta: Sector VII 1978

|

|

| The Strip outside the walls of Rome is actually the Appian Way. |

"They built in an isolated spot, Las Vegas, out in the desert, just like Louis XIV, the Sun King, who purposely went outside of Paris, into the countryside, to create a fantastic baroque environment to celebrate his rule. It is no accident that Las Vegas and Versailles are the only two architecturally uniform cities in Western history. The important thing about the building of Las Vegas is not that the builders were gangsters but that they were proles. They celebrated, very early, the new style of life of America--using the money pumped in by the war to show a prole vision . . . Glamor! . . . of style. The usual thing has happened, of course. Because it is prole, it gets ignored, except on the most sensational level. Yet long after Las Vegas' influence as a gambling heaven has gone, Las Vegas' forms and symbols will be influencing American life. The fantastic skyline! Las Vegas' neon sculpture, its fantastic fifteen-story-high display signs, parabolas, boomerangs, rhomboids, trapazoids and all the rest of it, are already the staple design of the American landscape outside of the oldest parts of the oldest cities. They are all over every suburb, every subdivision, every highway . . . every hamlet, as it were, the new crossroads, spiraling Servicenter signs. They are the new landmarks of America, the new guideposts, the new way Americans get their bearings. And yet what do we know about these signs, these incredible pieces of neon sculpture, and what kind of impact they have on people? Nobody seems to know the first thing about it, not even the men who design them."

| Being now fully aware of the role Wolfe played in the making the Learning from Las Vegas, my view of the VSBI project has changed. For a start, Learning from Las Vegas no longer seems lively and unique, rather now a bit cold and clinical. Furthermore, Learning from Las Vegas now feels even more agenda driven than specifically about Las Vegas, per se. It's odd (for me, at least) to now realize that Learning from Las Vegas could have been legitimately different than is it, could have been better even. |

www.quondam.com/33/3315k.htm | Quondam © 2018.02.07 |