Visigothic seige

"Thus began the third Visigothic siege, actually blockade, of Rome, an event whose outcome, after some eight centuries in which the imperial City had known impunity from foreign foes, created a shock of horror from Bethlehem to Britain. Once again Gothic bravery found itself daunted by the walls of Emperor Aurelian; the treachery that the Romans had feared in the beginning of 408 now in fact admitted the Goths by the Salarian Gate, 24 August 410, but not before the City had once again felt the bite of famine. Some buildings were burned, notably the Palace of Sallust the historian, which stood in its magnificence gardens near the gate of entry, perhaps the Basilica Aemilia in the Roman Forum, and the Palace of Saint Melania and Pinianus on the Caelian Hill, then one of the most fashionable quarters of Rome. Palaces and temples were plundered, some persons were slain or tortured to reveal their presumed hidden wealth; some virgins and other females were raped, but churches, especially the basilicas of Saints Peter and Paul, were spared and made places of refuge."

Stewart Irvin Oost, Galla Placidia Augusta: A Biographical Essay (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 96-7.

At first the somewhat agitated contour of the building can come as a shock to the student of our long-ago rationalist. Upon closer look we see the old principle of contained field in operation. The parallelogram figure is completed by implication. The beginning points of the major entry ramp make this necessary completion. The generating nucleus of the cubist scheme is the inserted 'Z' bar which moves through the center providing for centrifugal acceleration. The ramp is in three-dimensional torque, it is the aorta of the heart upon which the breathing depends. Like a bicycle pedal, when pressure is brought down upon the terminal ends, the whole building starts to revolve and spin. The curved blocks are the governors and screws-tightening, loosening-the run-away spatial fantasy.

John Hejduk, "Out of Time and Into Space" (1975).

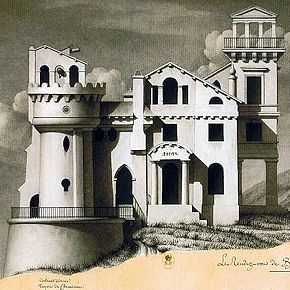

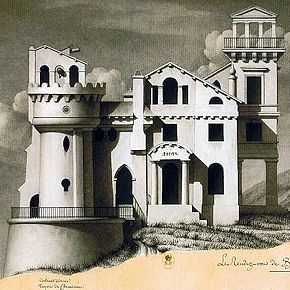

Jean Jacques Lequeu The rendezvous of Bellevue is on the tip of the rock 1777

But perhaps the most radical modification of the classical system of architectural figures is found in the work of the "visionary architects" of the French Revolution, Ledoux, Boullée, and Lequeu. These architects no longer believe that, as was the case in the Renaissance, the architectural figure corresponded to a hidden reality, revealed through Biblical or classical authority. Nonetheless they continued to use the Greco-Roman repertoire, whose meanings were seen to be established by social custom. But although they operated within a conceptual system inherited from the Renaissance according to which figures had metaphorical properties, they combined the traditional elements in a new way and were thus able to extend and modify classical meanings. The design of Lequeu called "Le Rendezvous de Bellevue" is an amalgam of quotations taken from different styles and organized according to 'pituresque' principles of composition. This building is a sort of bricolage made from figural fragments which are still recognizable whatever the degree of distortion. The case of Lequeu is perhaps different from that of Boullée or Ledoux because in his work classical composition seems often to be entirely abandoned. But even in an architecture based on picturesque principles, whose evident aim is to shock, the ability to provide this shock is dependent on the existence of traditional figures. One can , therefore, say of the work of all the visionary architects that it is not only an architecture parlante but lso an architecture qui parle de soi même. It consciously manipulates an existing code, even though in the case of Lequeu, it fragments this code. Emil Kaufmann and others have interpreted the work of Boullée, Ledoux, and Lequeu as being prophetic of the formal and abstrct tendencies in the new architecture of the 1920s and 1930s, and in particular the work of Le Corbusier. I prefer to see it as presenting a parallel to the present-day problem of the survival and reinterpretation of the figure of the rhetorical tradition.

Alan Colquhoun, "Form and Figure" in Oppositions 12 (1979), pp. 31-2.

| |

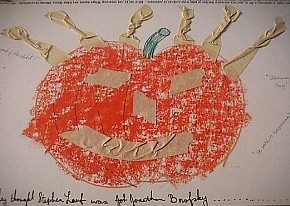

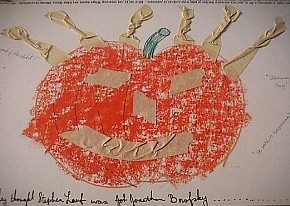

1984 Pumpkin Art The public opening of the Jonathan Borofsky exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art was 6 October 1984. A picture of Borofsky with numbers all over his face was on the cover of The Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday Magazine the same day. Thus informed I went to the exhibition that afternoon and found it magnificent, and that was before I became a part of it. After a number of 'standard' galleries displaying Borofsky's works, the exhibition culminated in a very large, double height room within which Borofsky manifest an installation. There were selected works all over the place, photocopies calling for nuclear disarmament all over the floor, and even a ping-pong table with a sign inviting museum visitors to play. An old woman was sitting on the only chair in the room, a metal folding chair next to a folding work table that looked as though Borofsky had simply left them there after he was finished. I waited for the woman to get up so I could sit there and observe all the reactions of 'shock' exhibited by all the other exhibition visitors. After sitting there for a few minutes, another older woman came up to me and asked, "You're the artist, aren't you?" I told her I wasn't, but she wasn't convinced. "Well, you're dressed the same as that figure of the artist up there hanging from the ceiling." It is true that both I and the figure of Borofsky "flying" over the room were wearing blue jeans and a red sweater. I was also wearing my beloved John Deere cap, however. Suddenly, I got an idea. On the table next to me was a pumpkin and a roll of masking tape. I started tearing off pieces of the tape and started giving the pumpkin eyes, a nose, and a mouth. Then I gave the pumpkin crazy hair standing on end with longer pieces of tape. A crowd started to gather around. "Are you part of the exhibit?" "I am now." Other questions were also entertained. Then a big bouncer of a museum guard came up and asked, "Were you told to do that?!?" I crossed my eyes and answered, "He made me do it." Then the guard's look changed from perplexed to angry, so I stood up and whispered to the guard that I did not intent to cause any trouble, and I will gladly leave the exhibit if he escorts me out. The guard obliged and told me I could stay in the rest of the museum, but "Please don't touch anything."

| |

1999.02.23 12:44

Re: irrational architecture

...with regard to contemporary architecture's relationship with the rational and the irrational. The vital, albeit still largely missing, ingredient of this analysis/phenomenon, however, is the creative-destructive nature of the metabolic (imagination). To reinforce my "theories" here, I offer the following quotation, along with some further analysis/explanation.

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia - Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1976), pp. 15-16.

"Rationalism would seem thus to reveal its own irrationality. In the attempt to absorb all its own contradictions, architectural "reasoning" applies the technique of shock to its very foundations. Individual architectural fragments push one against the other, each indifferent to jolts, while as an accumulation they demonstrate the uselessness of the inventive effort expended on their formal definition.

The archeological mask of Piranesi's Campo Marzio fools no one: this is an experimental design and the city, therefore, remains an unknown. Nor is the act of designing capable of defining new constants of order. This colossal piece of bricolage conveys nothing but a self-evident truth: irrational and rational are no longer to be mutually exclusive. Piranesi did not possess the means for translating the dynamic interrelationships of this contradiction into form. He had, therefore, to limit himself to enunciating emphatically that the great new problem was that of the equilibrium of opposites, which in the city find its appointed place: failure to resolve this problem would mean the destruction of the very concept of architecture."

Tafuri must here be taken to task because he comes extremely close to the truth about Piranesi and his large plan of the Campo Marzio, but he then falls fatally short of seeing the truth. Tafuri is absolutely wrong when he states, "Piranesi did not possess the means for translating the dynamic interrelationships of this contradiction into form." In truth, Piranesi worked very hard to "translate" the opposite yet necessarily linked notions of life and death (rational and irrational) within his great plan, and I have substantially documented Piranesi's (metabolic operations) in "Eros et Thanatos Ichnographia Campi Martii". Stated briefly, Eros names the life instinct and Thanatos names the death instinct, and Piranesi carefully delineates (between 1758-1762) both these "instincts" within the ancient city of Rome.

It is becoming more and more clear to me that any discussion of the rational and the irrational (in design and capitalism) tends to lead toward confusions unless they acceptingly incorporate the over riding creative-destructive nature of the metabolic (imagination).

2000.02.03 11:43

an answer to "Now what?"

Hugh Pearman states and asks:

Such being the case, we can conclude that Decon has run out of steam as a manifesto-led movement, and we must look to its successor. Ideas, anyone?

Steve Lauf replies:

Is Decon the only thing to have run out of steam? Has the now pervasive and generally accepted way of looking at and being critical of architecture also run out of steam? For example, does moving from seeing Decon as reactionary to now (maybe) seeing the New Austerity as the latest reaction really convey a sense of meaning beyond the oscillations of fashion and trend? Has each new "critical" building become nothing more than the latest "creation" of the now global fashion show? Likewise, has the element of shock become ingrained within the (elite) architectural profession, the same way shock has become "stock-in-trade" in a good deal of high fashion? [I'm not saying there is anything wrong with the architecture that receives attention and the industry surrounding it being akin to the fashion industry, but I do think there is something wrong about not recognizing the phenomenon as such.]

Here's how I now look critically at architecture (and urban design) both currently and historically:

What architecture is extreme?

What architecture is fertile?

What architecture is pregnant?

What architecture is assimilating?

What architecture is metabolic?

What architecture is osmotic?

What architecture is electromagnetic?

What architecture manifests the highest frequencies?

What I've found so far is that some architectures fall straight into some of the categories above while some architectures are categorical hybrids. Here are some examples:

the Pyramids, Stonehenge, St. Peter's (Vatican), Bilbao(?)--extreme, extreme architectures.

the Pantheon, Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, entry sequence of Schinkel's Altes Museum, Kimbell Art Gallery -- examples of the best osmotic architecture there is.

Classical Greek and Roman Architecture--pure architecture of fertility.

the Hindu Templ --the ultimate transcendence from an architecture of fertility to an architecture of pregnancy, whereas the Gothic Cathedral is an architecture of pregnancy, albeit virginal.

all of 20th century Berlin--the metabolic (create and destroy and create and destroy and ...)

To understand architecture of assimilation, look at the Renaissance, but also look to early 20th century Purism to understand assimilation in the extreme, i.e., purge.

Today's architectures are by and large assimilating and/or metabolic (contextual and/or 'deconstructivist'?).

You're very lucky if you ever see pure examples of electromagnetic or frequency architectures today because they are almost entirely architectures of the far off future.

There are many more examples to offer, but that's all for now.

In general, I see all architectures as reenactionary (as opposed to reactionary).

Architecture reenacts human imagination, and human imagination reenacts the way the human body is and operates. The human body and the design thereof is THE enactment. The human imagination then reenacts corporal morphology and physiology, and architecture then reenacts our reenacting imaginations.

|