| |

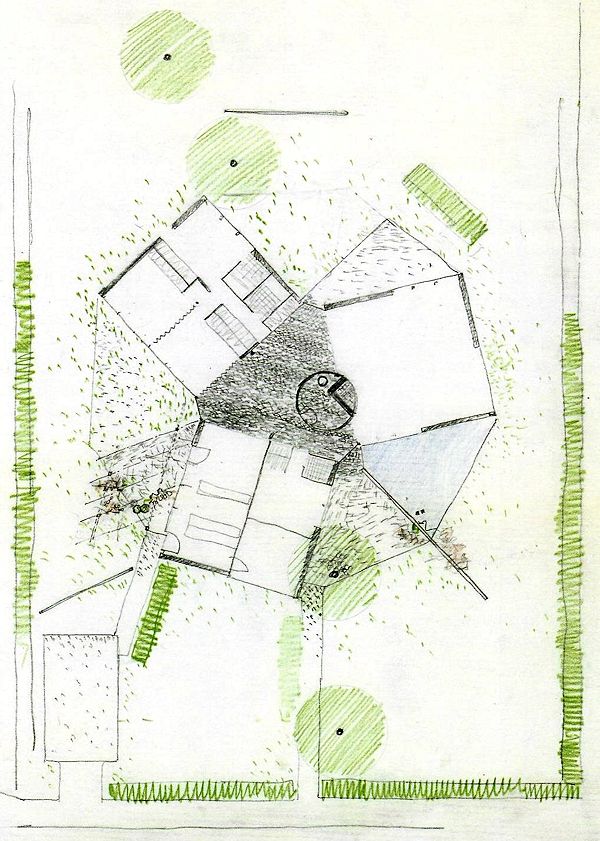

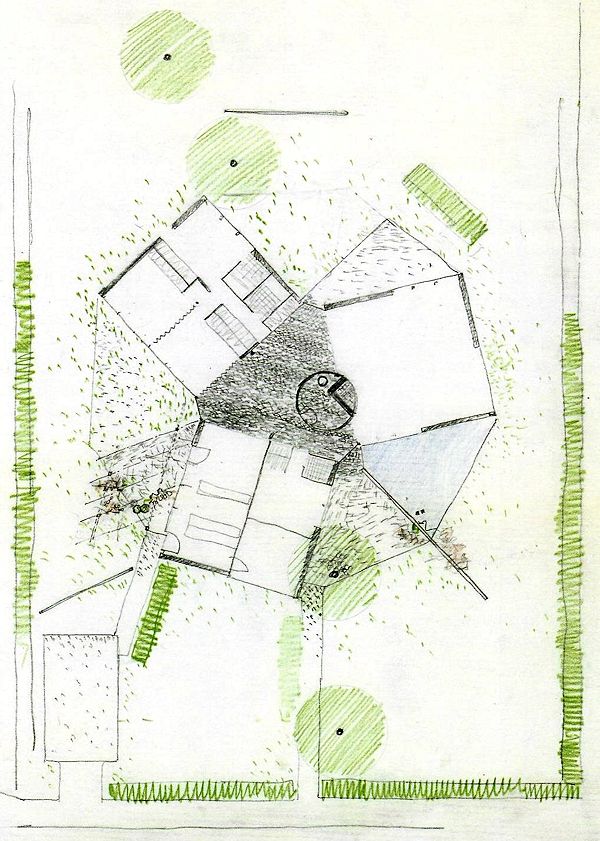

Leonard and Barbara Fruchter house, Wynnefield, Philadelphia, 1951-52. Plan. Louis Kahn, c. May-June 1952.

| |

This was a moment when Kahn, as MarkJarzombek describes it, began to question the "very nature of the American house;' challenging the prevailing consumer-oriented suburban building style that Jarzombek calls Good-Life

Modernism. Kahn created a series of simple plans that pronounced a "radical rethinking of the domestic environment." He was comingto the realization that"a room is a defined space-defined by the way it is made-by the way it gets a roof or ceiling and has its walls to separate it from the rest of the spaces." Jarzombek asserts that in these so-called pavilion plans-houses that are composed of separate, identical structures-the "fluidity of space, legibility of function, the hearth topos, and the organicist distinction between public and private have all been rejected. The repetition of identical spatial elements alone articulates the functional dynamic. The house is no longer a modernist machine, with its various parts designed according to the inner functional dynamic of suburban family life, but a conglomerate of smaller houses .... [It] no longer postulates a condition of suburban enlightenment, but rather aims to bring about an anthropological understanding of communal living. It makes allusions not to the conventional notion of modernity, but to African tribal huts." This was not unlike the settlement at Percé or the arrangement of houses Kahn presented in his Philadelphia Row House Study of1951-53.

This new approach to planning first appeared in April 1952 in Kahn's designs for the unbuilt Leonard and Barbara Fruchter House, which was intended for a site in the Wynnefield section of Philadelphia. 59 The plan comprises three identical squares joined to form a triangular element at its core, which Kahn saw as a flexible space "best not defined" by a specific use. A cylindrical volume, reminiscent of the central service element in Philip Johnson's recently completed Glass House, in New Canaan, Connecticut, is offset within the triangular core of the plan and contains a mechanical room and a fireplace. Each 24-foot-square block houses discrete functions. The living-room block (a volume several feet taller than the others) and bedroom block are positioned so as to maximize the potential of garden spaces on the relatively modest, flat site; these areas are enlivened by unusually shaped patios, a trellis for outdoor dining, a shallow pool at the entry, and walls built of terracotta chimney flues turned horizontally to create an engaging shadow effect. The service block, with kitchen, laundry, and storage and a guest room, has direct access from the entry court."

Underlying the logic of the Fruchter house plan was a grid of equilateral triangles measuring 12 feet on each side, which was a mark ofTyng's increasing interest in geometry and her impact on Kahn's thinking at the time. Her project for an elementary school, a work developed independent of Kahn and completed by February 1952, had explored the potential of geometrical forming principles through the design of an individual classroom housed within a discrete structural unit, a variation on the octet truss with integrated vertical support. Tyng's design preceded the Fruchter project and may have instigated the development of the pavilion-plan concept.

George H. Marcus and William Whitaker, The Houses of Louis Kahn (New haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 43-45.

|