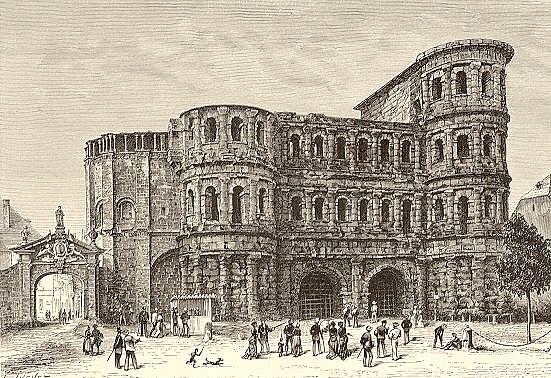

Porta Nigra (possibly 275-6 or early fourth century)

| |

The Porta Nigra, Trier (Trèves) (c. A.D. 300) though ornamented with teirs of crudely-carved Tuscan attached columns, enframing arcades above the lowest stage, is truly a defensive gateway, with a double archway equipped with portcullises and leading to an unroofed court which could be defended against besiegers Flanking semicircular towers form part of the structure, which is 35.05 m (115 ft) wide and reaches 28.96 m (95 ft) at its highest part.

The Porta Nigra is the quintessential Roman gate, designed at all costs to impress the wayfarer with the might of Imperial Rome. Such unusual features as it possesses are due simply to the fact that, like many of the late antique monuments of Rome, it represents a deliberate return to earlier Imperial models. In this case the models were first-century buildings such as the Porta palatina at Turin, or, in Gaul itself, the Porte Saint-André at Autun, the only serious consession to contemporary military planning being the greater robustness and depth of the towers, which were carried backwards the full length of the square internal courtyard so as to flank the inner and the outer gates alike. The decoration too derives from the same models, from the arched openings and framing orders of the galleries directly over the carriageways of the earlier gates. In this case, however, the motif has been taken and applied, incongruously, but with a certain barbaric magnificence, to the whole structure, two rows of arches running right round the whole building and a third right round the towers, 144 arches in all. The extraordinary crude finish of the masonary, sometimes citedd as analogous to the sophisticated rustication of the Porta Maggiore in Rome, is accidental: the building was never completed. There is no independent evidence to show exactly when in late antiquity this gate was put up. On historical grounds the most likely occassion would seem to be either when the town and its defences were rebuilt after the disastter of 275-6 or else during the earlier years of Constantines reign. The latter date would better explain why, like Constantine's bath-building, it was left unfinished.

J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), pp. 448-9.

| |

At the entrance to the old town and now next to the famous shopping street "Simeonstraße"", stands the Porta Nigra, a fortified Roman gateway whose truly colossal dimensions make it a unique monument of its kind and time. It was built of the distinctive light sandstone, by placing one row of huge blocks on top of another, and then joining them with iron clamps without using any mortar. Its construction dates from the 2nd century A.D., when Trier, until then an open town, was surrounded by walls with their towers and gates.

The Porta Nigra actually served a dual purpose: as a strong and effective defence and as an equally effective and impressive symbol of might and power. Its height is 30 meters and its depth 22 meters, while its front measures 36 meters in length. It has 2 carriage ways, each 7 meters high, leading through a windowless ground floor. But there are in all 144 windows with Roman arches on the first and second floors at the front, and looking across the inner court, provided with portcullis and secured by heavily strengthened gates. The two towers flanking the Porta Nigra, while built flush with the rest of the walls inside the courtyard, jutted outwards in massive curves at the front, where they faced the open fields, and were linked with the high walls (7 meters) surrounding the town, covering an area of 28500 acres.

With its roughly hewn blocks of sandstone, now weatherbeaten, darkened by the smoke of centuries, and shapeless through wilful destruction, it still retains its former impressive effect of massive strength.

The fact that this gate to the north had its equal counterpart to the town's southern entrance, and a similar gate to the east, and another, where the Old Bridge crosses the Moselle, strengthening this ring of walls, give a fairly accurate idea of how the power of Rome and its planning on a gigantic scale, gave the town its very shape.

Thanks to the conversion of the upper storeys of the gate and the Collegiate Church of St. Simeon into a twin church (11th cent.), in his memory, this Roman monument was preserved to prosterity.

|