(Circo di Massenzio e Tomba di Romolo, 309) Set in its magnificent brick-wall perimeter, the round tomb of Emperor Maxentius' beloved son Romulus is partially hidden by a medieval farmhouse. Next to it is Maxentius' private circus for chariot racing. The public entrance to this complex is 100 yards further along.

<

Unfortunately nothing remains of Maxentius' Villa, considered extraordinary by his contemporaries.

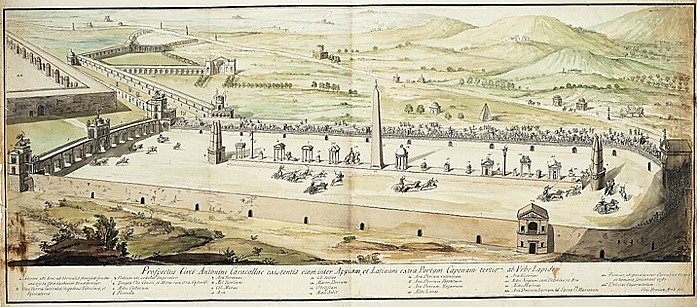

The Circus, nearly as big (520 yards/meters long and 92 wide) as the Circus Maximus, is worth taking time to visit since far more of the grandstand is visible than at the Circus Maximus. Although most of the tiers of seats have collapsed, the supporting structure is plainly apparent. Here 18,000 spectators once cheered the charioteers--or at least their favorite--in hopes he would win the 7- lap race and they would go home rich.

The long brick centerline "spina" divided the racetrack, dominated by the obelisk of Diocletian, now in Piazza Navona.

We can see how the ancient Roman builders lightened the weight of the masonry canopy arching behind and above the spectators' seats by inserting hollow pots in the volts (similar to those at the top of the Pantheon dome).

Romulus' Tomb has the same form as the Pantheon: a square porch in front of a drum. Immense, it stood in a large square surrounded by the walls you now see on three sides - but they were lined with a covered walk or portico. Visit the tomb's underground areas.

History

2C AD. This was the site of a villa owned by rich aristocrat Herod Atticus, tutor of two Emperors: Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

306-312. Maxentius ruled over the Roman Empire at its height.

309. Maxentius' son Romulus drowned in the Tiber River.

312. Maxentius drowned in the Tiber during his defeat by Constantine the Great.

As so often in late antiquity the imperial residence was accompanied by a circus, which is estimated as having held about 15,000 spectators, and which offers an unusually detailed picture of one of the racecourses that played such a large part in the social, and frequently also the political, life of later antiquity. The architectural niceties were many. Here one can see, for example, the ingenious irregularities of plan which ensured a fair start for the competitors in the outer lines; the starting-gates (carceres) set between the traditional pair of flanking towers (oppida); the two turning-points (metae) at either end of the central barrier (spina), which was placed well off-axis so as to allow for the crowding of the initial lap; the imperial box, overlooking the finishing line, and a second box near the middle of the opposite side for the use of the judges and organizing officials; the entrances and exits for the ceremonial parades of the contestants; and on the central point of the spina, in imitation of the Augustan obelisk in the Circus Maximus, the site of the Egyptian obelisk which Maxentius brought from Domitian's Temple of Isis in the Campus Martius and which Innocent X in 1651 retransported to the city to adorn Bernini's fountain in the Piazza Navona [which was the Circus of Domitian, also in the Campus Martius]. Constructionally the building is of interest for its bold use of alternative courses of bricks and of small tufa blocks, and for the large hallow jars used to lighten the mass of the vaulting that carried the seating, both characteristically late features which are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

John Bryan Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), pp. 421-424.

| |

14062302 psa/cri composite plans true north

Vincenzo Brenna, Aerial view of the Circus of Maxentius (c. 1770).

|