Eutropia | Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Rome |

|

|

1999.09.23 09:40 |

Jan Willem Drijvers |

Evelyn Waugh, Helena and the True Cross |

1. References are to the first edition of Helena of 1950. |

Introduction |

2. Speech Edinburgh Rectorial Election, The Times, 8 November 1951. In: Donat Gallagher (ed.), The Essays, Articles and Reviews of Evelyn Waugh (London 1983) 407. |

Around the main story Waugh digresses on religious movements like Mithraism and gnosticism, on political events of the time and on intrigues at the imperial court. The climax of the novel, Helena's discovery of Christ's cross, covers only some 14% of the book. The story is composed from the point of view of Helena - which is Waugh's view - and throughout breathes the admiration Waugh had for this saint of the Church.

|

3. Christopher Sykes, Evelyn Waugh. A Biography, London 1975, 318. |

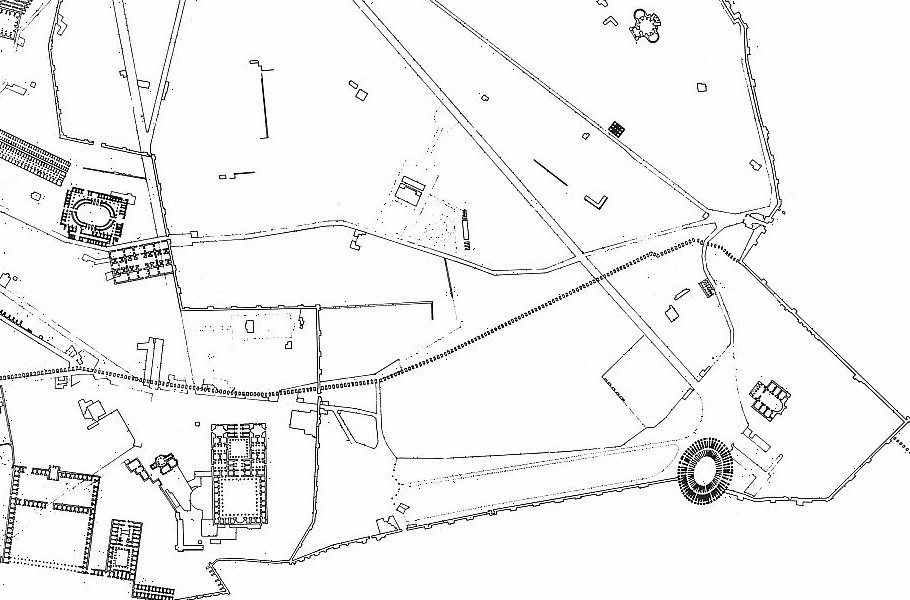

The gap in our knowledge about Helena's life lasts at least until 306, when in York the troops of Constantius proclaimed Constantine the successor of his father. It is probable that from this time on Helena joined Constantine's court. Constantine's main residences in the West were Trier and Rome. Ceiling frescoes in the imperial palace in Trier, on which Helena possibly is depicted, as well as a lively medieval Helena tradition in Trier and its surroundings, may be an indication that Helena once lived in this northernmost imperial residence. When in 312 Constantine had defeated Maxentius in the famous battle at the Pons Milvius, Helena probably came to live in Rome. The fundus Laurentus in the south-east corner of Rome, which included the Palatium Sessorianum, a circus and public baths (later called Thermae Helenae), came into her possession. Part of this palace was later transformed into the church of ´S. Croce in Gerusalemme'. In the 310s and 320s Helena must have been a prominent person at the imperial court and within the Constantinian dynasty. She held the honorary title of Nobilissima Femina and in 324 Helena received the title of Augusta.

|

4. Letter to Nancy Mitford, 28 January 1946: "I have got a working edition of Gibbon...Please get me sets of Cambridge Ancient Modern & Mediaeval History." |

Helena was modelled on Penelope Betjeman, wife of the poet John Betjeman, and a great horse lover. On 27 May 1945 Waugh writes to John Betjeman: 'As I told you I am writing her [Penelope's] life under the disguise of St Helena's...She is 16, sexy, full of horse fantasies. I want to get this right. Will you tell her to write to me fully about adolescent sex reveries connected with horse riding.' On 15 January 1946 he writes to Penelope Betjeman: 'Many months ago I wrote to ask your help with the hipperastic passages of my life of Helena...The Empress loses her interest in such things when she is married. I describe her as hunting in the morning after her wedding night feeling the saddle as comforting her wounded maidenhead. Is that O.K.?' In the beginning of February 1946 he writes to a friend: 'I am writing a very beautiful book about Penelope Betjeman's early sex life called ´The Life of the Empress Helena.''

|

5. To A.D. Peters: "I am finishing the life of St. Helena". Diary, 5 February 1948: "My Lenten resolution to start work on Helena has not come to much." Diary, 1 March 1948: "A hangover from Sunday's remission of Lenten abstinence...When the hangover is over I shall work on Helena." | Somewhere in February or March 1946 Waugh suspended work on Helena. The reason for this is not clear. It is assumed that other work demanded his attention like the publication of his travel stories (When the Going was Good, 1946) and the attention generated by Brideshead Revisited. It may also be that he became weary of Helena for the time being. He had of course not chosen an easy subject to write a novel about and he was unfamiliar with the genre of historical fiction. Early in 1948 he intended to work on Helena again but nothing came of it as appears from remarks in a letter to his literary agent and his diary.5 It would take more than a year before he actually resumed working on Helena. The writing apparently did not go very smoothly: 'I wish I could tell you that Helena progresses' (Letter 20 July 1949) and 'I write a sentence a week on the Empress Helena' (Letters 14 September 1949). Waugh, although himself very satisfied with the book, anticipated its failure with the public: '...Helena...is to be my masterpiece. No one will like it at all' (Letter 9 November 1949); and several weeks later he wrote: 'My Helena is a great masterpiece. How it will flop' (Letter 16 November 1949). In the beginning of March 1950 the book was finally finished: 'I have now written the last word of Helena and am quite out of work' (Letter 9 March 1950). In October of the same year the book was published by Chapman & Hall in London. It was dedicated to Penelope Betjeman. |

6. For more examples, see M. Morriss, D.J. Dooley, Evelyn Waugh. A Reference Guide,

Boston 1984, 36-40.

|

Criticism of 'Helena' |

14. Letter to Father d'Arcy, August 1930. In: S. Hastings, Evelyn Waugh. A Biography, London 1994, 225. |

Christianity |

15. Letter to John Betjeman, 9 November 1950. |

According to Waugh, the Roman Catholic church was the constant factor in past, present and future. To him the Church constituted western civilisation and was equivalent to civilisation itself. The Roman Catholic church was furthermore a support in a chaotic world and a safe haven. Waugh's religiosity is rather pragmatic and rational. He did not like mysticism and its vague and elusive discussions, preferring an understandable and concrete faith. This becomes very clear from a discussion between Helena and Lactantius which takes place after Helena had been present at a lecture about gnosticism:

|

16. About Constantine Waugh wrote in one of his letters: "He's not a sympathetic figure (to me)..." (Letter, 18 December 1951). In another letter he remarked: "[Constantine] is a shit in my book..." (Letter, 4 February 1946).

|

Historicity

|

|

In his book Waugh does not distinguish between what can be called more or less reliable historical writings and those sources which are downright legends. As a novelist he had to deal with the imaginative and legends stir the imagination. Legendary material which Waugh used for his book are of course the stories about the invention of the Cross. As mentioned above, these legends only originated several decades after Helena had visited Jerusalem. In these tales the discovery of the Cross is ascribed to Helena but we may safely assume, although Waugh himself would probably not agree, that Helena's discovery of the Holy Wood is fantasy. The legend was popular in Late Antiquity and spread rapidly. It is referred to in Ambrose's funeral speech for Theodosius the Great (395) and in the Church Histories of Rufinus, Socrates, Sozomen and Theodoret. Waugh knew these stories in which Helena is shown the site where the Cross was buried through a dream. He also knew the version in which the Jew Judas Kyriakos helped Helena finding the Cross. This version was widespread in the Middle Ages and an account of it was included in Cynewulf's Elene and in the Legenda Aurea of Jacob of Voragine (13th century). The theme of the dream is used by Waugh in the passage where the Wandering Jew, who is reminiscent of Judas Kyriakos, appears to Helena in her sleep and shows her the site of the Cross. Also other elements of the legend, like the recognition of the True Cross by means of a healing miracle, Helena's building of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the sending of part of the Cross and the nails to Constantine have been incorporated by Waugh. Another popular tale which was used by Waugh was the Sylvester-legend (Actus Sylvestri) which has the story of Constantine's conversion by the cure of the emperor's skin disease through the contact with baptismal water. Also the so-called Donatio Constantini is included by Waugh. According to this document, which is a historical forgery from the early Middle Ages, Constantine donated the City of Rome to Pope Sylvester and the Church. This piece of information is referred to in a conversation between Constantine and Sylvester. The emperor who has had it with Rome wants to found a New Rome, i.e. Constantinople:

|

www.quondam.com/82/8275c.htm | Quondam © 2016.11.13 |