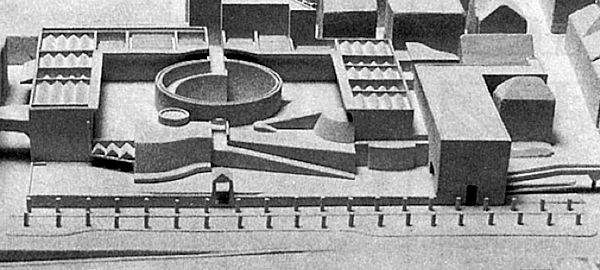

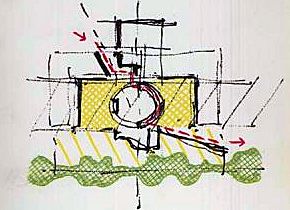

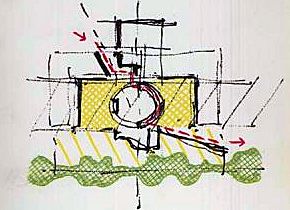

6Rowe's quotation confirms he was well aware of the screen of trees at the Staatsgalerie, yet he does not give any significance to the presence of the trees within Stirling's overall design intention. Proof of the trees' significance, however, may be gleamed from their being included within one of Stirling's early conceptual sketches.

"[I]n spite of its admirable merits (and they are extraordinary), Stuttgart is a building with no face. And it is not a question that no face could be seen because of a screen of trees. Instead, it is just the issue that, when considering intercourse with a building, its face--however veiled--must always be a desirable and a provocative item."

Colin Rowe, "James Stirling: A Highly Personal and Very Disjointed Memoir" in James Stirling - Buildings and Projects, (New York: Rizzoli, 1984).

Although Vidler does not make direct reference to the trees at Stuttgart, he makes a mistake in seeing the "original stoa" of the Altes Museum "marked by a terrace" at the Staatsgalerie instead of seeing the stoa marked by the gallery's "screen" of trees.

"Thus Stirling takes away not only the facade of the Altes Museum but also its front sequence of rooms turning the original palace plan into a U-shaped block reminiscent of the old gallery to one side. The site of the original stoa is marked by a terrace, reached by a ramp from street level. Then the stair, once set behind the stoa, is turned into a second ramp that rises from this terrace to the entrance and gives access to the courtyard in the rotunda."

Anthony Vidler, "Losing Face" in The Architectural Uncanny - Essays in the Modern Unhomely (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992), p. 92.

| |

7Laugier, Marc-Antoine 1713-69, was a Jesuit priest and outstanding neo-classical theorist. His Essai sur l'architecture (1753) expounds a rationalist view of classical architecture as a truthful, economic expression of man's need for shelter, based on the hypothetical 'rustic cabin' of primative man. His ideal building would have free-standing columns. He condemned pilasters and pedestals and all Renaissance and post-Renaissance elemants. His book put Neo-Classicism in a nutshell and had great influence, e.g., on Soufflot.

John Fleming, Hugh Honour, and Nikolaus Pevsner, "Laugier, Marc-Antoine" in The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., 1972), p. 170.

8origin of the column, etc.:

The pieces of wood set upright [for the rustic hut] have given us the idea of the column, the pieces placed horizontally on top of them the idea of the entablature, the inclining pieces forming the roof the idea of the pediment. This is what all masters of art have recognized.

Marc-Antoine Laugier, An Essay on Architecture, trans. Wolfgang and Anni Herrmann (Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, Inc., 1977), p. 12.

9aedicule : a small structure used as a shrine : a niche for a statue

10He wants to make himself a dwelling that protects but does not bury him. Some fallen branches in the forest are the right material for his purpose; he chooses four of the strongest, raises them upright and arranges them in a square; across their top he lays four other branches; on these he hoists from two sides yet another row of branches which, inclining towards each other, meet at their highest point. He then covers this kind of roof with leaves so closely packed that neither sun nor rain can penetrate. Thus, man is housed. Admittedly, the cold and heat will make him feel uncomfortable in this house which is open on all sides but soon he will fill in the space between two posts and feel secure.

Such is the course of simple nature; by imitating the natural process, art was born. All the splendors of architecture ever conceived have been modeled on the little rustic hut I have just described.

Marc-Antoine Laugier, An Essay on Architecture, trans. Wolfgang and Anni Herrmann (Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, Inc., 1977), p. 11-12.

| |

11Stirling's evolutionary theory of architecture:

[C]ontemporary architecture has its origins long before the 1920s or Adolf Loos. (How about the Japanese tea house for starters though, speaking personally, I might be inclined to go back to Egypt). I believe that the evolutionary theory of architecture is more interesting and is gaining ground over the revolutionary one--witness the current interest in (corrupt) Art Deco over the (pure) high MOD of Corb-Mies-Bauhaus. Every now and then revolutions do occur within the mainstream of architectural development and Modern Architecture was certainly one of these, but revolutions are the exception. The early pure style of Brunelleschi also was succeeded by architects who had a more relaxed and accommodating attitude to all of everything including architectural history and influences from every direction.

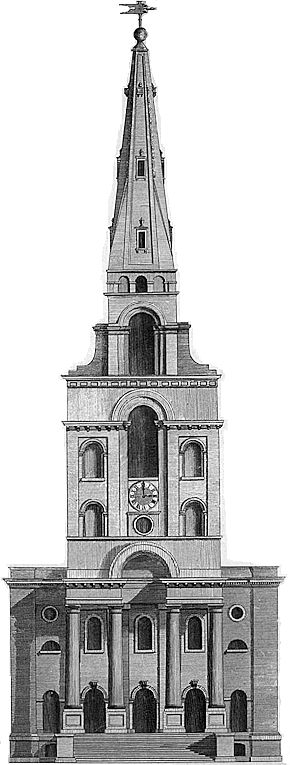

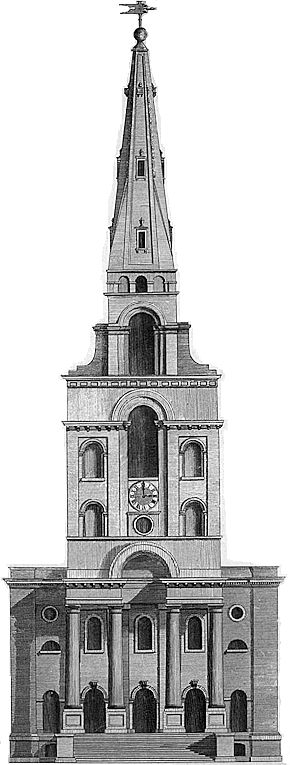

It is shocking to realize how very limited the language of contemporary architecture has become though, with the passing of High Style MOD, we have the opportunity once more to expand our vocabulary and remember our architectural lineage. The front of Hawksmoor's church at Spitalfields (London) comprises at least a Gothic spire, a French arch-de-triumphe and a Roman basilica, and this free-wheeling construction of elements was something which Schinkel and many other architects could do well; one admires their facility and envies their vocabulary. Never in the past (MOD Architecture excepted) have architects so completely rejected previous architectural forms and now is perhaps the time to acknowledge our continuity and remember our cultural background, wherever we come from, and this must be more important than any attempt at outright historical revivalism.

James Stirling, "Introduction and Comments" (to the House for K. F. Schinkel Shinkenchiku Residential Design Competition) in The Japan Architect, February, 1980, p.50-1.

The sense of "oscillation," as ascertained from the trees and aedicule at Stuttgart, also plays a role in Stirling's design philosophy:

We are alas too well known for a small part of our output, namely the University buildings of the early 60s particularly at Leicester and Cambridge and recently I've heard the comment 'Why has our work changed so much?' Whilst I think change is healthy, I do not believe that our work has changed. Maybe what we do now is more like our earlier work, and that oscillating process is still continuing.

James Stirling, "Acceptance of the Royal Gold Medal in Architecture 1980" in Architectural Design, July/August, 1980, p.7.

Our work has oscillated between the most 'abstract' modern (even High-tech), such as the Olivetti training school, and the obviously 'representational', even traditional, for instance the Rice University School of Architecture. These extremes have characterized our work since we began, but significantly, in recent designs (particularly the Staatsgalerie), the extremes are being counter-balanced and expressed in the same building.

James Stirling, "Design Philosophy and Recent Work" in Architectural Design, July/August, 1990, p.7.

| |

| |

12[W]e might well read Stirling's "empty center," with its ruined columns, as an ironic gesture that explodes the monumental focus of the building to the city, to imply the inhabitation of an already ruined monument or at least the establishment of a cemetery at its heart. And with the heart exposed and dead, the dismantling of all the other organs followed, culminating in the loss of face.

Anthony Vidler, "Losing Face" in The Architectural Uncanny - Essays in the Modern Unhomely (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992), p.95.

|