munus

2001.01.29

It is becoming more and more clear that Piranesi was well aware of Tertullian's De Spectaculis text, and indeed utilized it while planning out the Ichnographia Campus Martius. First it was the passage regarding the Equiria, and now there are passages regarding "munus", a death rite, where death games accompanied the funeral day. It is this new knowledge that explains the two circuses within the Bustum Hadriani.

2001.07.18

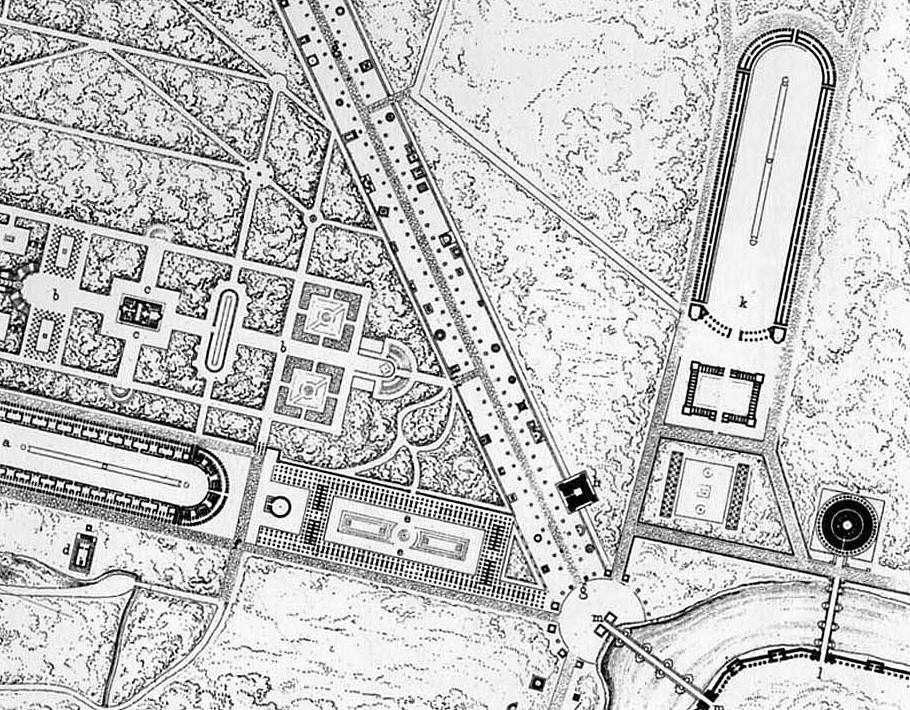

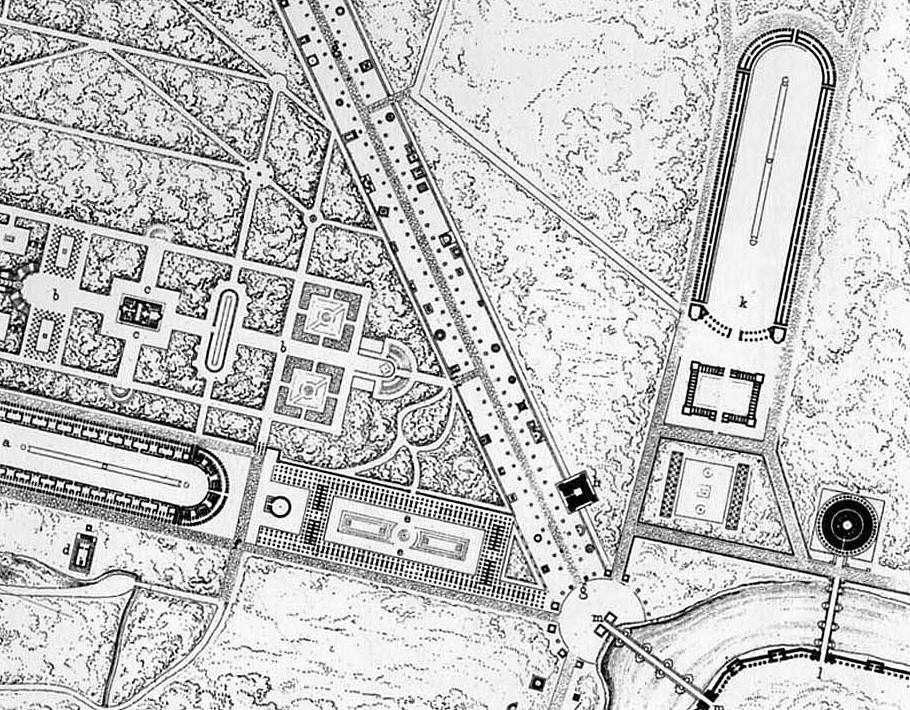

The Bustum Hadriani of the Ichnographia Campus Martius comprises two circuses flanking an enormous funerary complex, all on axis with the gigantic Sepulchum Hadriani. This design by Piranesi perfectly reenacts the ancient Roman 'munus'.

munus : a service, office, post, employment, function, duty : a work : the last service, office to the dead, i. e. burial : a public show, spectacle, entertainment, exhibition

For formerly, in the belief that the souls of the departed were appeased by human blood, they were in the habit of buying captives or slaves of wicked disposition, and immolating them in their funeral obsequies. Afterwards they thought good to throw the veil of pleasure over their iniquity. Those, therefore, whom they had provided for the combat, and then trained in arms as best they could, only that they might learn to die, they, on the funeral day, killed at the places of sepulture. They alleviated death by murders. Such is the origin of the "Munus."

Tertullian, De Spectaculis

By its very name, the Bustum Hadriani indicates a place of ritual involving death -- 'bustum' is the Latin for the place where the bodies of the dead were burned and buried. Piranesi integrates the Roman bustum with the Roman tradition of munus, and thus creates an architectural complex that is both bombastic mortuary and public arena.

Enframing the Bustum Hadriani is a succession of sepulchers for free men and slaves -- Sepulchra Libertorum et Servorum. These sepulchers, which follow an alternating repeated pattern of facing outside and inside, define the munus precinct, while at the same time serve as the place of interment for those of common or lower social standing. Note also that the pattern of inversion is again exercised in Piranesi's delineation.

There is archaeological evidence that a street lined with tombs was once in this area of Rome during the Empire's latter centuries, and perhaps that is why Piranesi positions the sepulchers here. Beyond that reasoning, however, it could well be that the physical evidence of Hadrian's Tomb and Circus plus a street of sepulchers in the same area inspired Piranesi to here reenact a grand place of munus.

2005.07.07 15:23

Krautheimer and Johnson

It just never occurred to him before that the Mausoleum of Romulus/Circus of Maxentius complex (which reenacts the almost two hundred years earlier Mausoleum of Hadrian/Circus of Hadrian complex) became the paradigm, albeit inverted, for all the Roman Christian "church" architecture immediately after the Basilica Constantiniani (St. John Lateran) and the Basilica San Pietro Vaticano. That aerial shot of the Mausoleum of Constantina (Santa Costanza) adjacent the circus-like dining hall first "basilica" of St. Agnes made it all so clear. If only the circus-like dining hall first "basilica" of Sts. Pietro and Marcellinus adjacent the Mausoleum of Helena were still to be seen from the air. How clever of Eutropia and Helena to invert the pagan 'munus' architecture into Christian 'munus' architecture, and how very clever of Piranesi to secretly hide all this architectural history information within the ever quaestio abstrusa Ichnographia Campi Martii.

2005.07.09 15:34

Re: NeoClassical Chili

Krautheimer published an essay, "Mensa-Coemeterium-Martyrium" 1960, where he earnestly speculates about the very real possibility that the early "Constantinian" basilicas (aside from St. John Lateran and St. Peter's Vatican) acted as covered graveyards where funeral banquets were held. He also noted how the shape of these basilicas was circus-like. When I read this essay (early 2005), I immediately though of the connection to the 'munus' ritual as related by Tertullian. And, after finding out more about the Mausoleum of Romulus/Circus of Maxentius complex (also early 2005), the "pieces" quickly fell together, particularly the connection of Eutropia to all this.

The Circus of Maxentius has been an unanswered question in my mind for a few years now, and now I think I know why Piranesi 'secretly' printed two different version of the Ichnographia Campi Martii--the Circus of Maxentius is the 'key' to the inversion of the pagan Roman Circus into the Early Christian 'basilica'.

[Piranesi, in La Anticitŕ Romane II (which predates the Campo Marzio publication by four years or so), delineated a "reconstruction" of the Basilica of St. Agnes--compare this with a present aerial view.]

What led me to Krautheimer's essay above was a footnote in R. Ross Holloway, Constantine and Rome, 2004.

2013.10.28 18:59

28 October

28 October 306: the Senate and the Praetorian Guard in Rome proclaim Maxentius as emperor princeps.

It could easily be said that the architecture of Rome (the city) under Maxentius represents the last flourish of genuine Classical in its true pagan milieu.

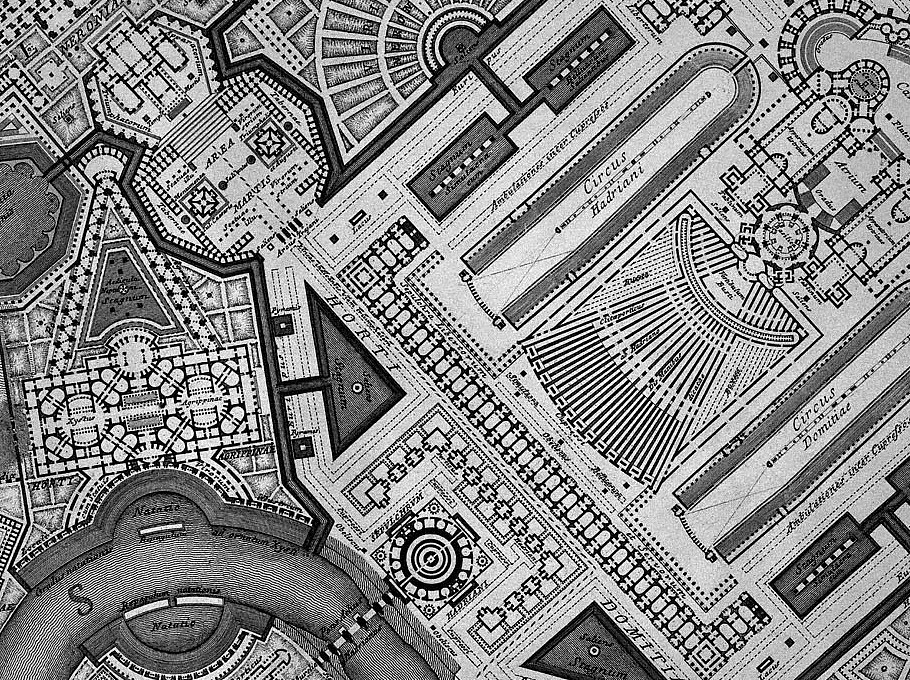

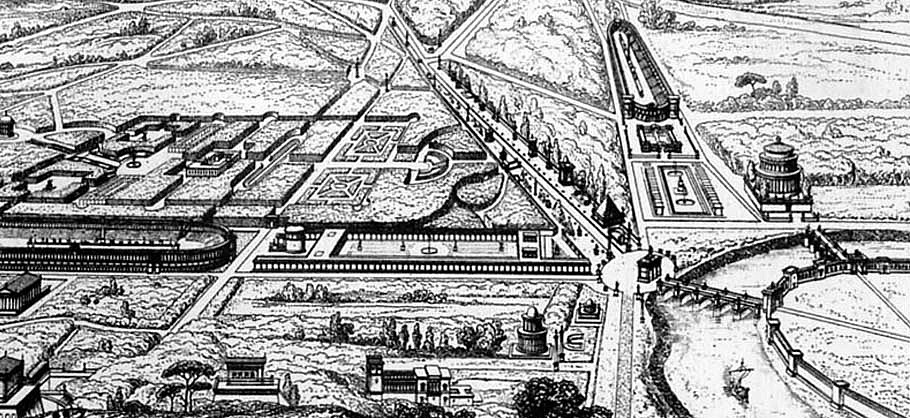

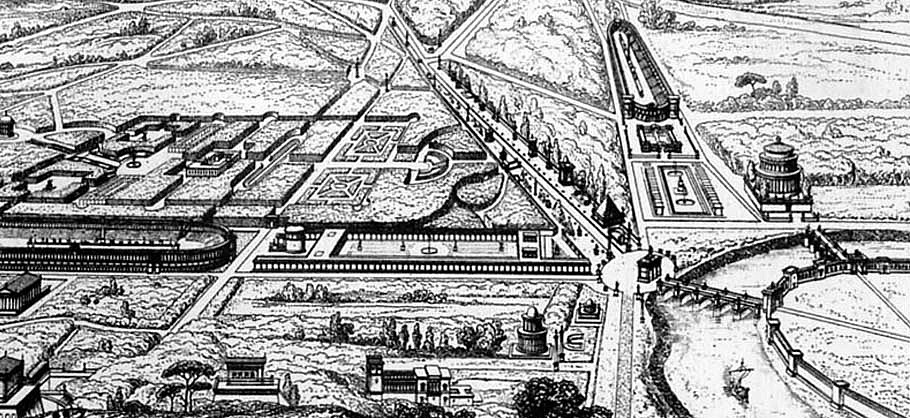

left: The Circus of Hadrian and the Mausoleum of Hadrian (135 AD), after Piranesi.

right: The Circus of Maxentius and the Mausoleum of Romulus (son of Maxentius) (c. 310 AD), on the Appian Way.

Both complexes, displayed here at the same scale with true north up, comprise the 'classic' Roman funereal paradigm of tomb, circus and dining hall, facilitating the "munus", a death rite, where death games and feasts accompanied the funeral day.

28 October 312: Maxentius offers battle with Constantine outside the gates of Rome near the Milvian Bridge. Maxentius suffers total defeat, himself drowning in the Tiber.

It is at this point that the architecture of Rome (the city) begins to represent a pagan/Christian hybrid, with stylistic influence coming from the North (Treves Augustum [today's Trier, Germany]), Constantine's Imperial capital, and from the East (Nicomedia [today's Izmet, Turkey]), the Roman Empire's power center since c. 280 AD.

left: The Circus of Maxentius and the Mausoleum of Romulus (son of Maxentius) (c. 310 AD), on the Appian Way.

center: The 'basilica' of Sts. Peter and Marcellinus (c. 314 AD) and the Mausoleum of Helena (mother of Constantine) (326 AD).

right: The 'basilica' of St. Agnes (c. 314 AD) and the Mausoleum of Constantina (daughter of Constantine) (c. 345 AD).

The three complexes, displayed here at the same scale with true north up, demonstrate how the tombs remained more or less the same, i.e., substantial round, domed structures, but the pagan funereal circus has morphed into a circus-shaped covered graveyard where feasts were held on the respective saint's death ('feast') day.

It is on record that the yearly commemorative feasts of saintly death days quickly evolved into quite exorbitant, if not all out drunken, several-day-long affairs, thus, by the beginning of the fifth century, Rome's somewhat unique circus-shaped basilica/graveyards were deemed inappropriate for 'church' architecture, closely coinciding with (St.) Augustine's writing of The City of God Against the Pagans.

| |

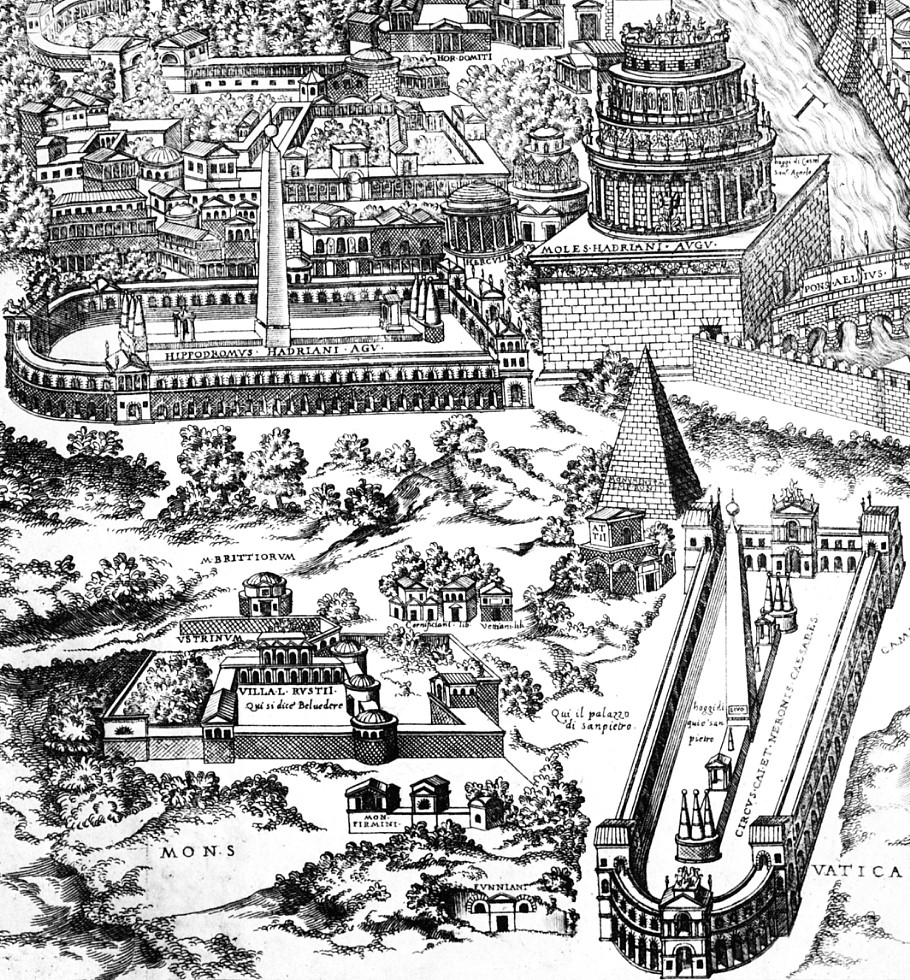

General view of the ancient quarter of the Vatican in the 2nd century.

from Paul-Marie Letarouilly, Le Vatican (1882).

14020101 PSAoCRI composite plans in situ, detail view

|