Eusebius sees Constantine for the first time in Palestine as Constantine and Diocletian make their way toward Egypt to suppress a rebellion.

| |

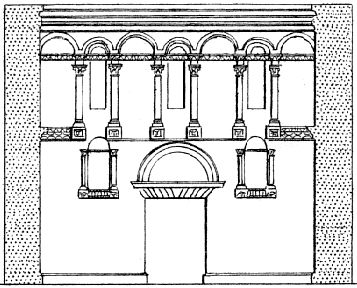

Elevation of the principal door of the Palace of Diocletian at Spaltro, called the golden door; the arcades and niches, enriched with columns and pilasters, supported by corbels; third century.

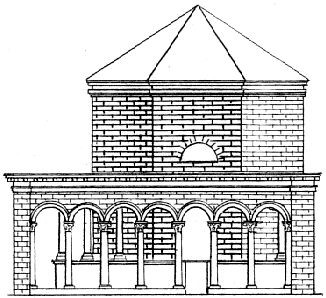

Side elevations of the octagonal Temple of Jupiter, within the enclosure of the Palace of Diocletian at Spalatro, the portico with niches supported by columns; third century.

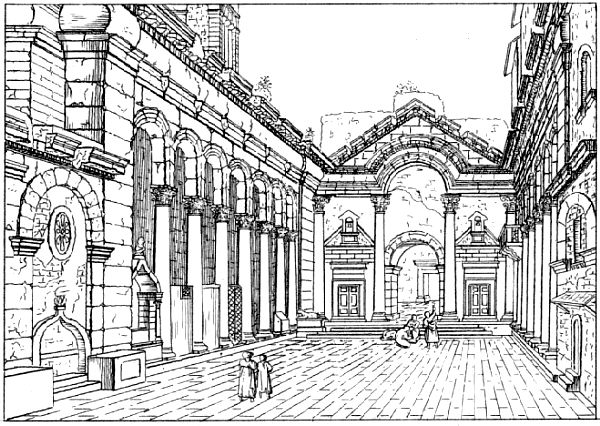

View of an interior court of the Palace of Diocletian at Spalatro; third century.

Seroux

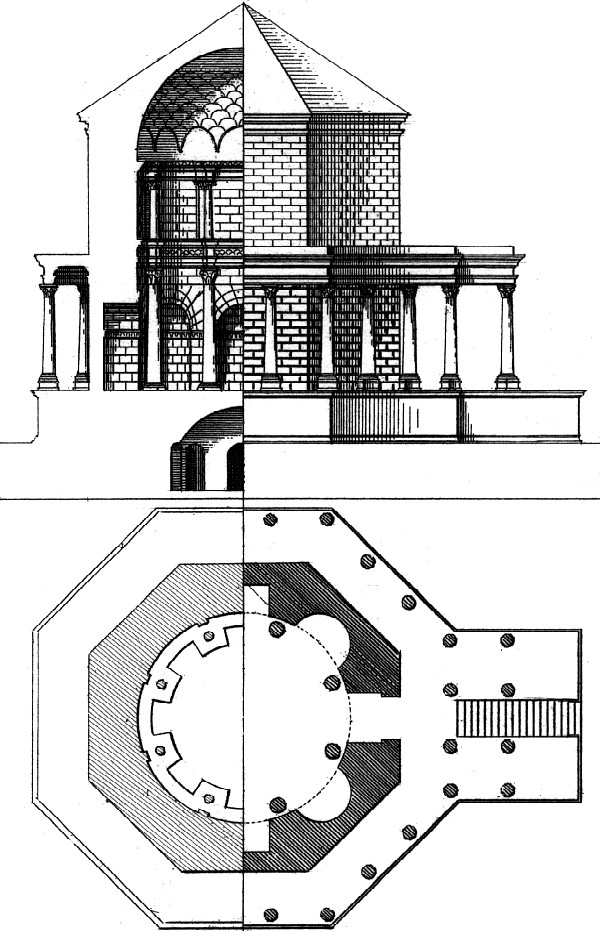

Side elevation, section, and plan of an antique Temple of Jupiter, within the enclosure of the palace of Diocletian at Spalatro. This building of the third century is given here to show the analogy which it presents to the principal baptisteries which were erected since that period.

Seroux

| |

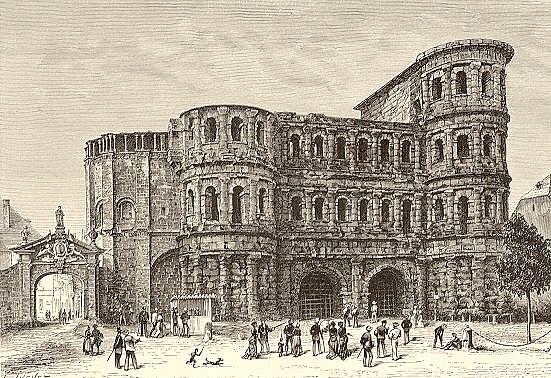

The Porta Nigra, Trier (Trèves) (c. A.D. 300) though ornamented with teirs of crudely-carved Tuscan attached columns, enframing arcades above the lowest stage, is truly a defensive gateway, with a double archway equipped with portcullises and leading to an unroofed court which could be defended against besiegers Flanking semicircular towers form part of the structure, which is 35.05 m (115 ft) wide and reaches 28.96 m (95 ft) at its highest part.

The Porta Nigra is the quintessential Roman gate, designed at all costs to impress the wayfarer with the might of Imperial Rome. Such unusual features as it possesses are due simply to the fact that, like many of the late antique monuments of Rome, it represents a deliberate return to earlier Imperial models. In this case the models were first-century buildings such as the Porta palatina at Turin, or, in Gaul itself, the Porte Saint-André at Autun, the only serious concession to contemporary military planning being the greater robustness and depth of the towers, which were carried backwards the full length of the square internal courtyard so as to flank the inner and the outer gates alike. The decoration too derives from the same models, from the arched openings and framing orders of the galleries directly over the carriageways of the earlier gates. In this case, however, the motif has been taken and applied, incongruously, but with a certain barbaric magnificence, to the whole structure, two rows of arches running right round the whole building and a third right round the towers, 144 arches in all. The extraordinary crude finish of the masonry, sometimes cited as analogous to the sophisticated rustication of the Porta Maggiore in Rome, is accidental: the building was never completed. There is no independent evidence to show exactly when in late antiquity this gate was put up. On historical grounds the most likely occasion would seem to be either when the town and its defenses were rebuilt after the disaster of 275-6 or else during the earlier years of Constantine's reign. The latter date would better explain why, like Constantine's bath-building, it was left unfinished.

J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), pp. 448-9.

|