2013.07.07 16:48

7 July

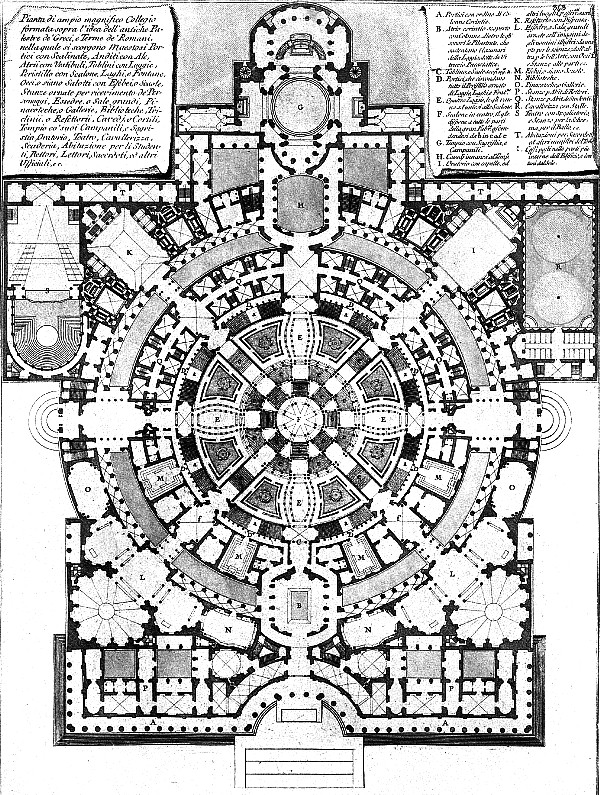

1998 ...since Piranesi came to live at the top of the Spanish Steps, he may then have placed the Horti Luciliani purposefully in the same location within the Ichnographia. If this is so, then Piranesi deliberately places himself (figuratively) within the garden of the father of Roman satire. ...find the exact location of Piranesi's home, check its location on the Nolli map, and then find the exact location within the Ichnographia. ...not sure if the exact spot will be significant, but it will be good to know nonetheless. ..find out if Piranesi has in other cases made a direct connection between himself, his work and satire. There is one engraving called Satirical vignette against Bertrand Chaupy something where an island(?) is made to look like a turd.

1999.05.24 11:24

interview 1

Most recently, I have become fond of the notion that "space" within cyberspace is always readily abundant, and, via hyperlinks, movement and circulation from "space" to "space" is easily facilitated. Moreover, hyperlink transitions within cyberspace offer the same abundant possibilities as the "space" itself since any channel or passage is instantly creatable. Because of this abundance, I do not regret cyberspace's basic lack of the third dimension. Indeed, generating a real cyber space and a real virtual place utilizing only two dimensions is our time's greatest architectural challenge.

The quest for a real two-dimensional architecture sheds new light upon the work of G.B. Piranesi, whose two-dimensional architectural oeuvre vastly outnumbers his three-dimensional manifestations. Nonetheless, Piranesi was a master of both two-dimensional and three-dimensional architectures. It is, however, Piranesi's two-dimensional work that is particularly poignant today -- albeit non-digital, all of Piranesi's architectural engravings reflect the work of the first consummate virtual architect. Above all, Piranesi's Carceri (Prisons) reveal the "torture" that a quest for real two-dimensional architecture engenders.

| |

1999.05.30 10:18

architectural theory

...I am now also thinking about 'Piranesi and the torture of two-dimensional space' as a topic to investigate.

2001.07.23 10:15

aesthetic correction

I'm almost finished reading Gerhard Kopf's Piranesi's Dream...

...a excerpt I thought this list might find inducing:

"But even worse was to come. I was assused of reveling in the ugly. What humbug! The theory of the fine arts, the legislation of good taste, the science of aesthetics were already highly developed and thoroughly refined in my time. Only the concept of the ugly, although they touched upon it everywhere, had remained behind. And actually what is ugly exists insofar as what is beautiful does. What is ugly comes into being from and with the beautiful. It is indignant at what is beautiful and likes to form an alliance with what is comical. In Nature what is ugly exists as little as what is beautiful or straight lines do, and it is a mistake to consider disease a cause of what is ugly. The realm of the ugly is much larger than the realm of sensual phenomena in general. Beautiful and ugly are not value opposites, rather at best opposites of stimulation. Concerning anything that is ugly it must be said that the relationship to what is beautiful that is neglected by it is included. Only what is ugly guarentees the aesthetic correction of tradition."

Just think about how true (and perhaps even axiomatic) that last sentence really is.

2001.07.23 17:17

for the love of email or ...

...Piranesi redux

I was hoping to send an email today to Professor John Wilton-Ely, the long standing Piranesi scholar. I am postponing my letter however, because he is today on his way to spending the rest of the summer at his Tuscany home, and I don't think he has access to email there. The reason for my email is to tell him I received the copy of his 1983 article on Piranesi, and to thank him for sending it to me. Wilton-Ely's package arrived at my house today, and I was surprised that he too finds fault with Tafuri's interpretation of Piranesi's Campo Marzio.

The correspondence between Wilton-Ely and myself began about a month ago. I recently found his webpage and email address through a series of fortuitous events. I took a change and sent him an email asking him if he knew that Piranesi's Ichnographia of the Campo Marzio exists in two printed states. About a week later Wilton-Ely replied by email and said he did not know that the Ichnographia was in two states, and that I appear to have made a remarkable discovery. In a subsequent email I supplied him with the data I have 'published' (via design-l and quondam) so far, and he in turn promised to send me a copy of his 1983 paper. A note Wilton-Ely sent along with the paper said he looked forward to 'continuing things' in September.

As you might well imagine, I'm very pleased with having made such a positive connection, and the reason I'm sharing all this here is because Design-L is one of the few (cyber)places where the "remarkable" Piranesi discovery was first (and immediately!) published. Of course, it can be well argued that cyber publishing lacks peer review, and is therefore not to be altogether trusted, but, then again, cyber publishing, especially via email lists that automatically archive, offers the satisfying aspect of verifiable and timely public record, as well as the invitation for (peer) review.

2001.12.04 11:36

Piranesi Prison dates, etc.

In "Notes From Underground" Berman incorrectly dates the Imaginary Prisons of Piranesi. Instead of 1745 for the first state and 1761 for the second state, 1749-50 is the correct date for the first state, as is 1761 for the second state. Thus Piranesi was between 29 and 30 years old when he first published the Invenzioni Capric. Di Carceri (Fanciful Images of Prisons).

Relative to Piranesi's other publications up to 1749, it is interesting to note that the Carceri are not dedicated and/or not commissioned, meaning they are works executed of Piranesi's own volition (a relative rarity in Piranesi's complete oeuvre). Moreover, it is worth comparing the Carceri with Piranesi's first published work, the Prima Parte Di Architetture (Part One of Architecture and Perspectives: Imagined and Etched by Gio. Batt.a Piranesi). The Prima Parte, published in 1743 when Piranesi was 23 years old, can easily be considered Piranesi's initial design portfolio.

Observed together the Prima Parte and the Carceri manifest a double theater where the first "play" is inversely reflected in the second "play". (Note too that the second "play" comes with two "acts".)

| |

2001.12.04 11:36

Piranesi Prison dates, etc.

In "Notes From Underground" Berman incorrectly dates the Imaginary Prisons of Piranesi. Instead of 1745 for the first state and 1761 for the second state, 1749-50 is the correct date for the first state, as is 1761 for the second state. Thus Piranesi was between 29 and 30 years old when he first published the Invenzioni Capric. Di Carceri (Fanciful Images of Prisons).

Relative to Piranesi's other publications up to 1749, it is interesting to note that the Carceri are not dedicated and/or not commissioned, meaning they are works executed of Piranesi's own volition (a relative rarity in Piranesi's complete oeuvre). Moreover, it is worth comparing the Carceri with Piranesi's first published work, the Prima Parte Di Architetture (Part One of Architecture and Perspectives: Imagined and Etched by Gio. Batt.a Piranesi). The Prima Parte, published in 1743 when Piranesi was 23 years old, can easily be considered Piranesi's initial design portfolio.

Observed together the Prima Parte and the Carceri manifest a double theater where the first "play" is inversely reflected in the second "play". (Note too that the second "play" comes with two "acts".)

I don't like having to do this (because it implies that some editor is not really doing their job), but it must be pointed out that Joseph Rykwert made (at least) one factual mistake within The Seduction of Place (2000). On page 150, Rykwert states:

"The attempt to provide a mimetic "condensation" of another place and time is not new. Centuries ago pilgrimages to remote and sacred places were replicated for those who could not afford to leave home. The fourteen [S]tations of the [C]ross, which you may find in any Roman Catholic church, are a miniaturized and atrophied version of the pilgrimage around holy places in Jerusalem."

The above is complete misinformation. The Stations of the Cross do not represent a "pilgrimage around holy places in Jerusalem." The Stations of the Cross are a ritual reenactment of what Christ experienced on the day of His crucifixion.

Interestingly, the example that Rykwert should have put forth is that of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, the church in Rome built within the Sessorian Palace, the imperial home of Helena Augusta, which today houses Christianity's most valuable relics (of the "Stations of the Cross"). Additionally, Santa Croce (which means Holy Cross) is built upon ground brought back by Helena from Golgotha, site of Christ's crucifixion. Santa Croce is indeed one of Rome's primal pilgrimage churches.

|