2012.09.03 16:52

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

2026 Vision?

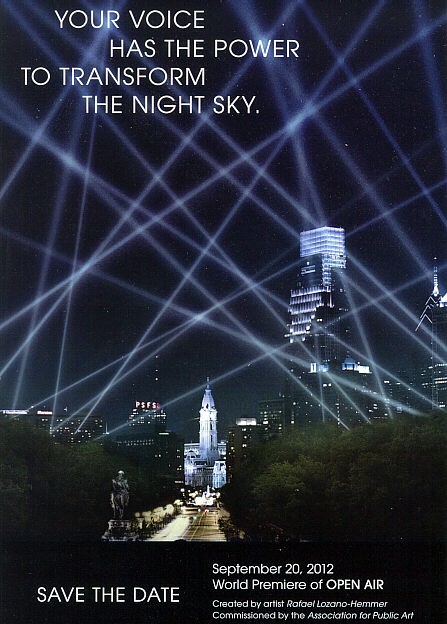

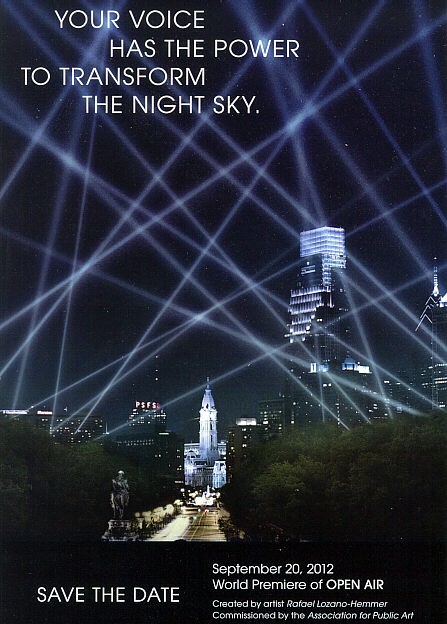

This past Saturday I received a postcard inviting me to the world premiere of Open Air:

This fall, head to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and take part in the largest crowd-sourced public art experience ever seen in Philadelphia. Open Air will employ 24 searchlights, a free mobile app, and your voice and GPS position to transform the night sky. Created for Philadelphia by internationally acclaimed artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer.

I was immediately reminded of Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 (1 December 1972).

Today I went online to see if Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 is anywhere mentioned as inspiration for Open Air, and there is no 'official' mention of Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 in conjunction with Open Air except a commentor to one of the Open Air news posts, Andy Blanka, did mention that Venturi & Rauch had already designed something similar. In any case and forty years later, Open Air will be an un-official tribute to the ideas of Venturi, Rauch, Scott Brown and Izenour (who did the above drawings).

Ideas for the Bicentennial were first published within the October 1969 issue of The Architectural Forum--"The Bicentennial Commemoration 1976"--a rare piece of writing where Denise Scott Brown precedes Robert Venturi as co-author. Seen now in retrospect, many of the ideas proposed were ground-breaking and indeed influential in the long run, and still relevant today with regard to current notions of architecture and advocacy. To offer one flavor of the piece I parsed out the sentences that contain the words 'little' and then the sentences that contain the word 'big':

"It is significant that Expo 67, hailed as a triumph, produced little innovation in architecture or structure."

"Still very much employed and perhaps even more challenged, since now their ingenuity would be taxed to make much out of the little available for building, to make meaningful in built structures the serious aims of the nation, and on top of this to make our show fun, seductive and delightful."

"The Commemoration should serve, starting now, as a major aid to economic development of the black community, otherwise we shall have little to celebrate in 1976."

"Why should Little Upper Begonia strive to show us its plastic factory when it has so much to say on the harnessing of teen-age revolt or on the housing of rural migrants?"

"An Expo based on interaction of people in meeting places spread over several cities could look a little low."

"We recommend, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

"We advocate, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

There is an authors' note at the end of the piece:

We owe much in the development of our ideas to Mr. Tom Wolfe (who coined the phrase "electrographic architecture"), to Mr. David A. Crane, to members of the Philadelphia Bicentennial International Exposition Planning Group, and to the Philadelphia Citizens' Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community, and all their advisors.

This brings to mind a curious footnote within Charles Jencks' The Story of Post-Modernism (2011):

Tom Wolfe lampooned architects' inability to reach the exuberance of Las Vegas sign artists, or 'Electrographic Architecture', in many articles. One key essay, republished in his collection Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1965, was written in his neo-hysterical style--'Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas!!!' Tim Vreeland has told me that when Venturi and Scott Brown were visiting Albuquerque circa 1968, he put a copy of Wolfe's book on the bedside table, and the couple were so impressed they drove off to see Las Vegas the next day. Their own shift in taste-culture towards commercial vernacular and Route 66, culminated first in an article, 'A Significance for A&P Parking Lots' (1968) and then the whole argument, Learning from Las Vegas, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA/London), 1972. Thus the Las Vegas polemic may date from Wolfe's humorous assault on professional taste, and that he too was to carry on with another attack on Minimalist Modernism, From Bauhaus to Our House, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1981. Reyner Banham took the Las Vegas sign artists in another direction, towards the dematerialized city of electronics, light, and environmental control. His The Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment, Architectural Press (London), 1969, inverts the Corbusian definition of architecture--'pure forms seen in sunlight'--to 'coloured light seen in impure forms'.

To clear up some of the chronology suggested above:

1965: On her way to California to teach in the School of Environmental Design at Berkeley for the spring semester, Scott Brown stops off in Las Vegas. That summer she travels in the southwest [including Albuquerque?]. In September, Scott Brown moves to Los Angeles and accepts the position of co-chair of the Urban Design Program at UCLA, where she remains through 1967. She recruits Venturi to act as a visiting critic.

1966: Scott Brown invites Venturi to visit Las Vegas with her for a four-day trip. In November the two travel the Las Vegas strip, from casino to casino, being alternately "appalled and fascinated" by what they see. ["Next I was taken to Las Vegas in 1966 by Denise Scott Brown--prepared a little by Tom Wolfe and a lot by Baroque Rome. Out of that trip came our studio at Yale and then our book Learning from Las Vegas."]

Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture is published by the Museum of Modern Art as the first in an intended series of occasional papers addressing issues of architecture and design (actual distribution is not until March 1967).

I doubt very much I'll actually see Open Air in person, but I could easily make a virtual model of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976. Or better yet, I should start publishing my ideas for the Semiquincentennial!

| |

2012.10.31 11:43

atemporality at work?

Do precedents and/or antecedents work against the notion of atemporality?

As much as I like the collages of Archive of Affinities, I am, at the same time, not prepared to fully explain why I like them nor what it is exactly about the collages that I like so much. Varnelis' description of the collages as "atemporality at work" is indeed intriguing, and I want to know more. Consequently thinking for myself, it is the search for and research of the precedents and antecedents that provide a context for a better understanding of the collages of Archive of Affinities.

Anecha, a fellow admirer of the collages of Archive of Affinities, feels the "recent work may not be postmodern in the design sense, in the sense of a particular style, it is explicitly postmodern in methodology and ideology. Postmodernism didn't stop because people stopped believing in it: as Lethem notes, 'the tools that postmodernism left us have entered mainstream usage, they are free to become distinct from any style.' Ultimately postmodernism is the framework in which creators have been, and are still operating." I suppose the question is: How do these new collages from Archive of Affinities operate? And from what context do they operate?

Interestingly, the words a-temporality and a-temporal make an appearance within the text of Collage City:

"Presented with Marinetti's chronolatry and Picasso's a-temporality; presented with Popper's critique of historicism (which is also Futurism/futurism); presented with the difficulties of both utopia and tradition, with the problems of both violence and atrophy; presented with alleged libertarian impulse and alleged need for the security of order; presented with the sectarian tightness of the architect's ethical corset and with more reasonable visions of catholicity; presented with contraction and expansion; we ask what other resolution of social problems is possible outside the, admitted, limitations of collage. Limitations which should be obvious enough; but limitations which still prescribe and assure an open territory."

"Excursus: We append an abridged list of stimulants, a-temporal and necessarily transcultural, as possible objets trouvés in the urbanistic collage."

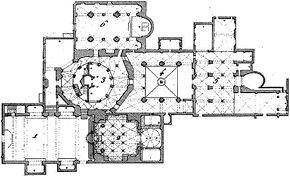

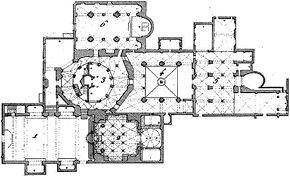

...the Basilica of St. Stefano, Bologna, thirteenth century, a religious compound where the Court of Pilate and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Jerusalem were/are specifically reenacted.

1. The six churches of which the plans are here given, nos. 1 to 6, are thus grouped at Bologna, under the title St. Stephen, the church no. 1, however, being more particularly dedicated to the saint.

2. Subterranean Church of S. Lorenzo, beneath that of St. Stephen, and serving as the Confession.

3. Church of the Holy Sepulchre; according to tradition the baptistery of St. Peter and St. Paul, no. 6, the first cathedral built at Bologna.

4. Another church, called the Court of Pilate.

5. Church of the Trinity.

6. Church of St. Peter and St. Paul.

| |

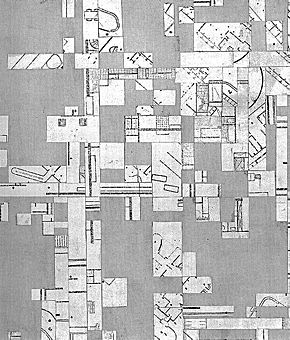

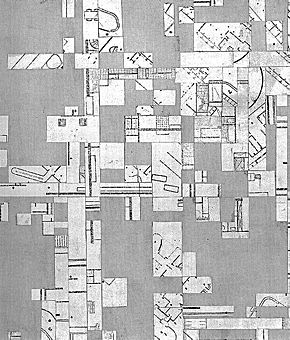

COLLAGE/DANIEL LIBESKIND. Collage challenges the notion of architecture as a synthetic construct--a mixture of various creative disciplines. The idea of achieving such a synthesis by a hollow manipulation of heterogeneous elements can result only in 'synthetic flaws'. Architecture cannot compete with film, total theater, technology, psychology, or sociology, to achieve relevance. By drawing from these motley disciplines it constructs only hybrid conglomerations without integral syntactic necessity or organic unity. The expedient definition of architecture as a 'total environmental system' is popular among designers, users, producers, critics, etc., because it allows the concurrence of all these points of view without provoking a conflict between them. The theory that architecture is a synthesis along Wagner's theory of the theater, allows and in turn justifies, the complete exploitation of any devise; be it plastic, programmatic, or technical, in order to achieve a superficial stimulation of our sensibilities. In this way the accidental and arbitrary parade in the guise of a new methodology. The attempt at incorporating these foreign technologies or sophisticated mechanizations does not lead to dynamism of thought but rather to enervating physical mobility. Progress in this direction is therefore futile from the conceptual view, for no matter how much architecture exploits these resources, it will always remain inferior to a discipline such as film, for its ability to manipulate sequences, control speed, or create instantaneousness. The analytic approach, devoid of multiple means, limited to the existing materials, determined by historical realities, can fashion a new framework for concepts and ideas by releasing us from the determinism in both syntactic and semantic domains. It is a kind of poverty that is being proposed. A poverty of matter to be compensated by the development of the conceptual ideal. The use of 'garbage' reveals a possible method which can penetrate beyond the surface appearance of meaning and form, and strike at the very depth of conditioned relations; generating through a new grammar radically different ways of perceiving, thinking, and ultimately perhaps acting. [c 1969]

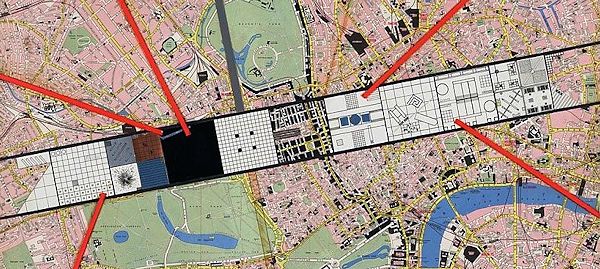

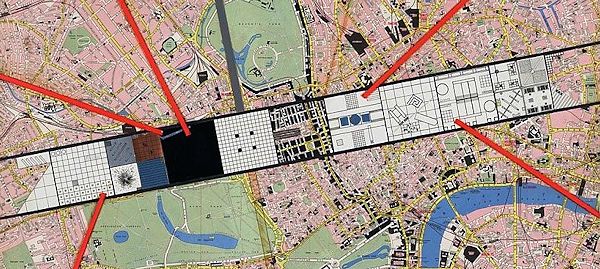

Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture

This study describes the steps that will have to be taken to establish an architectural oasis in the behavioral sink of London.

Suddenly, a strip of intense metropolitan desirability runs through the center of London. This strip is like a runway, a landing strip for the new architecture of collective monuments. Two walls enclose and protect this zone to retain its integrity and to prevent any contamination of its surface by the cancerous organism that threatens to engulf it.

Soon, the first inmates beg for admission. Their number rapidly swells into an unstoppable flow.

We witness the Exodus of London.

The physical structure of the old town will not be able to stand the continuing competition of this new architectural presence. London as we know it will become a pack of ruins.

Rem Koolhaas, Madelon Vreisendorp, Elia Zenghelis, Zoe Zenghelis, 1971.

|