2015.03.09 15:03

Orange County legislators fail to save Paul Rudolph's Government Center

Albeit "forward the discipline" is not a term I used, I'll repeat what I just wrote:

Although the "classical" work is the best of the office's output, it is still just average when compared to the vast amount of very good classical architecture to learn from. My main critique of the American classical architecture designed today is it's timid, textbook style.

The fact that "classical" architectural design has elaborately evolved over the years from 500BC to the nineteenth century is not at all evident in the (American) classical architecture being built and designed today. The ongoing innovation that classical design once was is simply absent now.

2015.03.09 17:29

Orange County legislators fail to save Paul Rudolph's Government Center

Seems that an actual criticism is being conveniently ignored.

Albeit "forward the discipline" is not a term I used, I'll repeat what I just wrote:

Although the "classical" work is the best of [David Schwarz's] office's output, it is still just average when compared to the vast amount of very good classical architecture to learn from. My main critique of the American classical architecture designed today is it's timid textbook style.

The fact that "classical" architectural design has elaborately evolved over the years from 500BC to the first half of the 20th century is not at all evident in the (American) classical architecture being built and designed today. The ongoing innovation that classical design once was is simply absent now.

If you want today's "classical" architecture to be professionally respected, you need to step up the game. Otherwise, why should what is really just average architectural design be getting high praise?

2015.03.09 20:44

The Battle of the Ancients and the Moderns (sequel #______ )

If you think I believe that "modern technology=modern design," then you are mistaken. As the 20th century progressed, all architectural design became more and more an expression of newly developed technologies. For example, the existence of skyscrapers is largely dependent on elevators, and, even though most of the early skyscrapers are done in a classical style, their design is modern where the classical aspect is only a styling. The Tuscaloosa Court House is not a genuine classical building--for a start, the plan is a modern/classical hybrid, at best. And, like classical skyscrapers, the Court House is only classical in styling (and a very average deployment of classical styling at that).

And to clarify a big mistake you made, architecture was not the main technology for the storage and dissemination of information prior to the printing press. For example, much of the knowledge of the ancient world that fueled the Italian Renaissance came from Byzantine manuscripts brought to Italy by monks, etc. fleeing the Turkish invasion of Constantinople in the mid 15th century. Gothic cathedrals were 'texts' for illiterates, while literate people were reading and writing manuscripts.

| |

2015.03.09 21:45

Orange County legislators fail to save Paul Rudolph's Government Center

I am not superimposing a modernist value structure on classical architecture. I am merely looking at the history of Classical architecture itself. In broad terms, each generation (and 'nationality') strove to make improvements on what was done before--sometimes in the form of refinements, and sometimes in unprecedented innovations, like the introduction of the arch and dome into the classical lexicon. The Roman circus, for example, finally reached its point of highest refinement with the Circus of Maxentius (c.309AD) which is very late considering that Rome was founded c.750BC. Come the Renaissance, when classical architecture became both a practical and academic exercise, we see all the architects trying to out do each other in style and design. Michelangelo stands out as he almost exclusively focused on the design of moldings, and the results of his constant experimentation remain unparalleled in their classical innovations, which, in turn fuelled Mannerism and the Baroque. Neo-classical architecture is due largely to the 'rediscovery' of ancient Greek architecture and the publication of their details and measurements.

Classical architectural design today just doesn't seem to have any that aliveness, rather more like rigor mortis set in.

ps. A couple of weeks ago I was looking through all the HABS collection drawings featuring architecture in Philadelphia. EKE, I thought of you and wondered whether you knew about this online resource, as there are so many measured drawings of all kinds of America architecture, full of plans, elevations and details, and how all this information could really aid in making American classical architecture more innovative if not even more American, again.

pss. Check out Gunston Hall, Virginia. I did the 'Chinese' Dining Room drawings.

2015.03.29 11:51

The Architect as Totalitarian

EKE, the point of your last post doesn't follow logically. Describing classical architecture as "the architecture of European colonial repression" or Southern Colonial architecture as "the architecture of slavery" is a criticism of the Classical style, particularly pointing out that Classical Architecture is not a universal sign of rightful order and beauty. Again, the criticism is of the style of architecture, but not of the architects of classical architecture themselves. Yes, one can be critical of Le Corbusier's words, but in no way is his style of architecture rightly considered fascist or Nazi.

2015.03.30 09:57

The Architect as Totalitarian

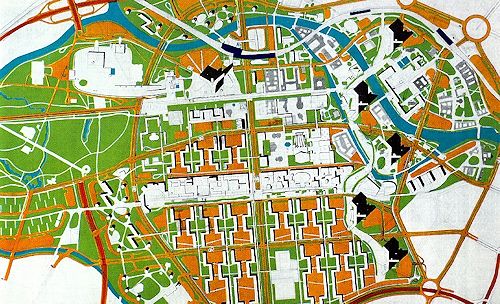

EKE, the game you're trying to play is beginning to be childish and bratty. If you want to call out Le Corbusier's style of architecture, at least use examples of Le Corbusier's architecture. For example, there is Le Corbusier's International Planning Competition for Berlin, 1958.

You can maybe start by calling out veiled Nazi references in the plan. (Ha!)

Otherwise, you might actually learn something (about style and design) by actually looking at the project.

| |

2015.04.26 11:16

what is 'beauty' in Architecture?

Sinclair Gaudlie's Architecture: the appreciation of the arts/1 (1969) comes to mind.

Contents

1. The Nature of the Art

2. Communication and Interpretation

3. The Roots of Ugliness

4. The Source of Delight

5. Scale, Order, and Rhythm

6. Weight, Force, and Mass

7. The Awareness of Space

8. The Dialogue of Space and Structure

9. The Dialogue Continued

10. The Play of Shape

11. The Enrichment of Form

12. The Play of Light

13. Judgment and Design

14. Eloquence, Aptness, and Style

15. Place, Time, and Society

The first footnote in "The Roots of Ugliness" reads:

By 'critic', here and elsewhere, I do not, of course, mean a professional fault-finder but rather the kind of observer who can voice opinions which command respect because the assumptions on which they are based are clearly more than unthinking prejudices. And I assume it to be a characteristic of the good critic that he is perpetually testing his assumptions against new experience.

Now, if only there was a way to quiet the non-professional fault-finders.

2015.05.27 11:40

New photos of E. Fay Jones' Thorncrown Chapel unveiled to mark 35th anniversary

The notion of "whether imitating Frank Lloyd Wright's style in a quite direct way, especially now in the 21st century, qualifies as a viable and productive pursuit in and for architectural design" was not the issue. You said "imitating Frank Lloyd Wright is invariably not productive at all," and I asked for evidence of that supposition. Your reply offered no real evidence and a loose justification of your supposition, and that is what I have issue with.

I can more readily agree with the notion that FLW's architecture has so far 'proven' to be an uneasy paradigm for other architects to follow. Yet such a supposition would necessitate a study of FLW's designs more so than the designs of the 'imitators' to see where the difficulties lie. Your language--imitating Frank Lloyd Wright is invariably not productive at all--comes off more as an ongoing deterrent for designers to even try as opposed to an accurate assessment of the situation.

Regarding Thorncrown Chapel, it looks to me that whole lower zone, where people are in direct contact with the building, is all imitation FLW, and the whole upper zone doesn't necessarily evoke FLW at all.

2015.06.01 21:22

Why do Americans love this style of architecture so much?

Look at the work of Charles Moore from the late 1970s through the 1980s; that's the real precedent for this "style". It's all really a side-effect of Charles Moore's post-modern style. It was/is extremely easy for commercial architects to copy, and it fell in perfectly with then-newly popular building products like Dry-Vit/EIFS. The late 1970s-1980s designs of Michael Graves were also a strong influence. Perhaps call it the Post-Modern Side-Effect Style.

Venturi usually gets blamed for this stuff, but really, look at the work of Charles Moore because that's where you'll see near identical detailing.

| |

2015.06.01 21:34

Why do Americans love this style of architecture so much?

In many ways, you can describe Charles Moore's post-modern style as neo-vernacular craft.

2015.06.01 21:55

Why do Americans love this style of architecture so much?

neo-vernacular craft in style

I live in a developer built house from 1975. It's all an easily repeated kit of parts with very little craft involved at all. Craft in construction since the mid-1970s is more a rare occurrence than the norm.

2015.07.02 12:40

Why are people so fascinated with classical architecture?

Volunteer, all you're doing is confusing the issue, which, as far as I'm concerned, is architectural design manifestations of the Classical Ideal in the 21st century.

Read your Harbeson to see/learn how size, scale and proportion need to work in tandem.

Generally, I agree with tintt and Miller in calling out historical examples of architecture in terms of their respective periods and styles, instead of naming anything with a classical order, pediment or some moldings as 'classical'. Antique classical architecture pretty much ended with the reign of Maxentius in Rome. And, while Maxentius was ruling in Rome, Constantine was ruling in Treves (today's Trier, Germany), and we see there the beginnings of 'Roman' architecture exhibiting a strong influence from the eastern half of the Empire (you can even say the very roots of Romanesque). The first half of the 4th century comprised a huge paradigm shift in 'Roman' architecture, not least of which was the moving of the Imperial capital to Constantinople. This is where Seroux d'Agincourt's The History of Art through Its Monuments from Its Decline in the Fourth Century to Its Renewal in the Sixteenth starts off--'middle-aged' European architecture is remarkably exuberant.

And for a concise overview of 'size, scale and proportion' see the Grande Durand, where all the plans are at the same scale and all the elevations are at the same scale (but all the elevations are twice the scale of their respective plans).

2015.07.03 10:22

Why are people so fascinated with classical architecture?

Did lots of reading last night.

Started with Demetri Porphyrios' "Classicism is Not a Style" (1982)--"Classical architecture constructs a tectonic fiction out of the productive level of building. The artifice of constructing this fictitious world is seen as analogous to the artifice of constructing the human world. In its turn, myth allows for a convergence of the real and the fictive so that the real is redeemed. By rendering construction mythically fictive, classical thought posits reality in a contemplative state, wins over the depredations of petty life and, in a moment of rare disinterestedness, rejoices in the sacramental power it has over contingent life and nature."

Then read DP's "Cities in Stone" (1984)--"The locus classicus for the conviction that there exists a universal and rational certainty about architecture and the city has been, of course, Vitruvius, Filarte or Alberti. But whereas for the classical world this foundation of certainty was God's divinity, for the post-Enlightenment world of modernity human reason was to take the place of God. Descartes' Meditations stand as the great rationalist treatise of modern times and his demand that we should rely only upon the authority of reason itself has been at the very center of modern life. And in his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant describes 'the domain [of pure reason] as an island, enclosed by nature itself within unalterable limits. It is the land of truth--enchanting name!--surrounded by a wide and stormy ocean, the native home of illusion...'"

I'm beginning to think that if I found DP's successive writings, I'd also find the evolution of whole new 'philosophy of classicism', one that parallels a small group of contemporary architect's straight imitation/copying of late 19th century Beaux-Arts stylings.

Then I remembered Joseph Rykwert's "Classic and Neo-Classic" (1977), and, while looking for that on my bookshelf, I also found Porphyrios's "The 'End' of Style" (also 1977 but after Rykwert)--"Thus, the nineteenth century produced no theory of origins--unlike Classical and Enlightenment architectural thought." I think this marks the beginning of DP's own "theory of origins".

Alas, it is within Rykwert's "Classic and Neo-Classic" that the history of "classic" is found: "the word [classic] refers to an ancient tradition. The sixth king of Rome, Servius Tullius, graded all Roman society into six groups called classes according to their income; all were expected to contribute money to the defense of the state, except the lowest, the proletarii, who had no money to contribute and therefore could only give their children, their proles. Ancient writers derived the word classicus from calare, "to call" (classicus was a contracted form of calassicus); the word was even applied to the trumpets with which Romans assemblies were summoned, and this meaning was retained throughout the Middle Ages. By the time of the late Rebuplic, however, the word classicus was no longer used for the members of any class but the first, or the richest. ... By the seventeenth century, classicus, "classic" meant not only excellent and choice, or first-class, but also antique, the antique had by then assumed the role of an unquestioned and unquestionable model of excellence. Not only writers, painters, and architects, but also statesmen and religious reformers based their practice or policy on the emulation of the antique."

Also did some reading in Samir Younes' The True, the Fictive, and the Real" The Historical Dictionary of Architecture of Quartremere de Quincy (1999) which provided a somewhat unique interpretation of how architects are to employ the history of architecture, and this morning found Bruno Foucart's "The modernity of neo-greeks" (1982) which starts with a most provocative statement: "In fact, the liberation of Greece and its opening up to the Western World coincided with the end of the Neo-Classical period."

|