There is always a catch, the secret seeming to offer how to catch Lequeu's work, but this work only offers secrets on how to catch fish, Lequeu's "As fishing is an agreeable pastime, here is how to catch fish by hand." This fishing, however, is not agreeable to art historical interpretation, such interpretation caught by its own recipes of how to keep birds from flying away, its own strategies of how to catch fish. Interpretation reaches a limit in trying to de-limit Lequeu's work, having to put it at the limit, as a limit to the history of art and architecture, Lequeu's work always exceeding the limits of history, writing his own history, re-writing history. A history of art and architecture would like to wipe its hands clean of Lequeu's work, putting his work in the sanitary confines of the sanitarium, but Lequeu is the one who offers up theories of cleaning, his treatise "Letter on the fine soaping which might be called Paris Soaping, addressed to Mother's Families...."

Interpretation labors at these points, but it does not work, Lequeu's work working on the blind spot of interpretation, casting doubt on the object of interpretation, not offering an object for interpretation, or, rather, offering objects that object to interpretation, the intrusion of interpretation, objects that hold secrets that are cryptic, buried in crypts, the history of art and architecture unwilling to leave this work buried, breaking into the crypt, but burying the rotting corpus that is found there, burying Lequeu's work into the margins, and failing to address Lequeu's problematization of the crypt, his use of the cryptic, cryptic marginalia such as "[t]he flesh eater, firmly divided in three graves, is covered by slabs of marble," written above the tombs in Elevation of Tombs in the Field of Physical Recreation.

It is language that is "cryptic": not only as a totality that is exceeded and untheorizable, but inasmuch as it contains pockets, cavernous places where words become things, where the inside is out and thus inaccessible to any cryptanalysis whatever- for deciphering is required to keep the secret secret. The code no longer suffices. The translation is infinite. And yet we have to find the key word that opens and does not open. At that juncture something gets away safely, something which frees loss and refuses the gift of it. (Maurice Blanchot)

The secret is encrypted into Lequeu's work, but any means of de-ciphering the code was buried into the cryptic vault that Lequeu refers to in his donation to the Bibliothéque Royale, Lequeu always ciphering his work, and his name always serving as a cipher....

Lequeu's work holds the attention of interpretation, inviting interpretation, inciting interpretation, but failing to be interpreted, only existing through this failure of interpretation, refusing interpretation, re-fusing to be fused to interpretation, with interpretation, only confusing interpretation. Lequeu is not revealed through his work, his work only revealing "Lequeu," whatever that may mean. I have suggested a scaffolding that provides terms with which I have tried to describe something that for lack of a better name I have called "Lequeu," but such a scaffolding must be thrown away, a scaffolding that only exists outside of the work, which only serves to make the façade more fetching. Lequeu's far-fetched explanation throws interpretation for a loop, leaving interpretation caught within circular arguments that fail to ground Lequeu's work. One cannot try to approach Lequeu's work from the outside. One has to try to live within Lequeu's work, even if that space, that work is not for the living. One must be inside the work herself. A self, however, is never simply either inside or outside, always both and neither. The scaffolding obstructs as much as it repairs, leaving marks, leaving traces, leaving scars. Lequeu's work in turn scars, de-faces all scaffolding, leaving all scaffolding in ruins, as ruins. While one tradition of the history of art and architecture does not see how Lequeu's negation affirms, another tradition does not see how his affirmation negates. All the while Lequeu leaves these interpretations in ruins. I can neither offer a synthesis, nor simply a new negation or affirmation. The self never synthesizes and is only ever synthetic, my interpretation just as much ruined by Lequeu's ruinous runes.

| |

A tradition of the history of art and architecture has withdrawn Lequeu's name from among the most important architects of his time, and such a gesture may be justified. Lequeu may not be an architect, if such a designation matters. In terms of his impact on the events of his time, such a withdrawal is deserved. As long as history wants to be a story of those who did, who accomplished, who had a direct impact, who produced, then Lequeu has no place within such a story of the progress and triumph of agency. But, if we wish to look at a history in terms of those impacted by events, responding to events, critiquing the results of events, providing critique, Lequeu is useful in having left behind and leaving beyond his frivolous archaeology. Neither completely in his time, nor out of his time, Lequeu's work is suffused with questions of temporality and space, the visible and the invisible, mind and matter. In other words, Lequeu's work is not just engaged in questions pertinent to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, but is also engaged in issues that will be taken up by philosophy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, or rather these issues may be addressed in and through Lequeu's work....

In a sense, Lequeu provides the best list of terms that are used in his œuvre in his "Alphabetical summary of terms used in this work," a list that has no terms, no terms being used by Lequeu, Lequeu trying to arrive at possible terms, terms for gender as possibility, a body as possibility, a self as possibility, a negotiation that is an on-going process. This is just another blank within Lequeu's work, more literal than others, and also more ephemeral, a blank that exists in a chain with the unstated promise, his frivolous secrets that he reveals, his proclamations, his complaints, his notices, his explanations, all of these mobilizations of guerrilla forces whose battle never seems to end, except in a draw, a chain of images and writings that offer no way of enchaining Lequeu's work, of binding Lequeu's work, Lequeu's work always leaving interpretation in a double-bind, bound to fail....

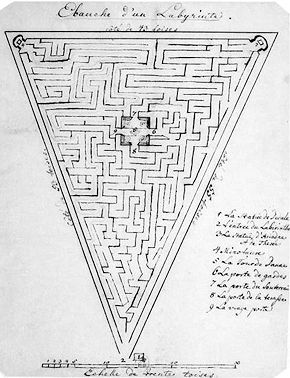

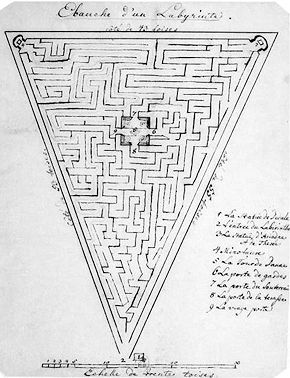

Sketch of Labyrinth

| |

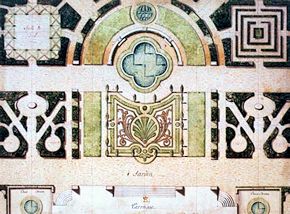

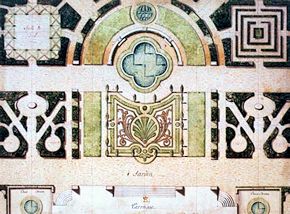

Plan for a Garden

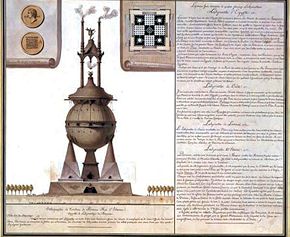

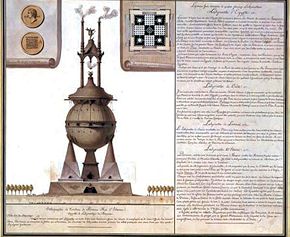

Elevation of the tomb of Porsenna, king of Etruria, known as the Tuscan Labyrinth, 1792

Drawing, a Weapon

In Lequeu's courtship, in his attempted address, all his advertisements, all his warnings, all his complaints, there is an engagement with the issues and ideas of his period. Lequeu draws on many of the sources and people of the late eighteenth century. In a very literal, frank way, Lequeu's work draws upon the images and plates that may be found in other books of the eighteenth century. His far-fetched explanation declares as much in its emphasis on imitation but at a distance. This appropriation on Lequeu's part has been well documented by others, although this has been done as a way of disparaging Lequeu's work as being "merely imitative," and not "imaginative." There are several examples of Lequeu's appropriation that may be cited/sighted. Lequeu's Monument to Athena comes from Le Lorrain's Chinea of 1746. Lequeu's Chinese drawing room is based on plate 10 of Sir William Chamber's Designs for Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils. Lequeu takes the image of the windmill used in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, a windmill that has been abstracted from its physical location, and Lequeu re-inscribes this windmill into its actual location in his Vertical section of the Mill at Les Verdiers.

| |

Lequeu draws not only on visual sources, but literary sources throughout his Architecture Civile. He draws not only on Ancient sources such as Pliny and Horace, but also on more modern sources such as Jean Doubdan's Voyage de la terre sainte and Eugène Roger's La Terre Sainte for his depictions of Nazareth. Lequeu's Nouvelle Methode draws on Caspar Lavater's theory of physiognomy for much of its text dealing with identifying attitudes and personality from the features of the face. Metken links Lequeu's Subterranean Labyrinth for a Gothic House to Abbé Terrasson's novel Séthos. Lequeu's process of cross referencing and detailed marginalia may be seen in relation to the Encyclopédie and the culture and writers surrounding this project. Lequeu's work, in its annotation, deals with issues of air circulation, clean water supplies, sanitation, functionality, and issues of an agrarian society raised by many of the treatises on health concerns, city planning concerns, and the ideology of the physiocrats, concerns that may also be seen in the work of Ledoux, among others. In these senses, Lequeu's work may be seen as addressing the issues of his age, as being very much a part of it, representing common concerns shared by others.

This is a process of imitation, an imitation of his fellow artists, a laying fallow from his fellow artists, which Lequeu carries over to the type of subject matter he approaches and the way he organizes this subject matter. Lequeu writes on the back of some of his drawings and proposes in his Architecture Civile to depict '[b]uildings of different peoples scattered throughout the world. Architectural compositions, regular and irregular, Etruscan, Tuscan, Flemish, European, Egyptian, Chinese, Persian, Indian, Gothic, and others," repeating a popular theme for books of architectural plates during this period, and participating in an orientalism common to architecture during the eighteenth century. This occurs in the midst of his treatise whose original stated aim, an aim that is repeated on nearly every page of the first 46 plates, reads, "Drawings which represent with figures the colors and means for the tinting of plans, sections, and elevations of opaque bodies." In this concern for shading, the concern with shadows throughout his work, Lequeu may be seen repeating a concern with shades and shadows that plays such a prominent role in the work of Boullée.

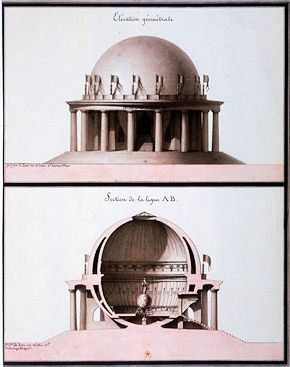

Lequeu's drawings Temple of the Earth and Temple to Sacred Equality (1793) may and has been compared with Boullée's Cenotaph to Newton, and Ledoux's Plan of the Cemetery at Chaux. In other plans, such as Second entrance to the infernal cavern of the Chinese garden and Temple embedded in mountain, Lequeu may and has been concerned with issues of constructing buildings directly out of the earth that is being worked upon, a thematics of the rock and the column, a natural architecture that is repeated in Ledoux's Entrance Door to the Salines at Chaux, Auguste Chevalle de Saint-Hebert's Elevation du projet de château d'eau, François-Joseph Bélanger's Quatre états successifs du premier projet pour le "rocher," Neuilly's La Folie Sainte-James, and Boullée's Temple Dedicated to Nature/Reason, an architecture that engages Rousseau's notion of naturalism, while Lequeu's Place of Persian prayer... may be seen as being wrapped up in Masonic symbolism and Zoroastrian imagery. This is all to say that there is a narrative that may show Lequeu as being very much a part of his time, but such a narrative only detects the sources that Lequeu draws upon, failing to take into account the distance in Lequeu's imitation, the critical distance of Lequeu's imitation, his imitation at a distance, which distances him from his contemporaries, which critiques his contemporaries, which addresses his contemporaries otherwise, sending their work away, turning their work away, making their work other. Lequeu's work draws upon the work of his contemporaries deeper than is usually acknowledged and provides a deeper critique of their work than is usually addressed, Lequeu's work always addressing in a cryptic way, through the crypt and in the crypt, at a distance, in imitation.

| |

In addressing Lequeu's address, in trying to locate Lequeu's address, a tradition of art history and architectural history has failed to address how Lequeu problematizes the address, of how he warns that he has changed addresses and that he is little known in the neighborhood in which he now resides. There is a whole problematics of drawing, addressing, and appropriating that has yet to be broached. I am offering only a few suggestions, suggestions around the address, on how to possibly address Lequeu's work, work which has been ab-sent, sent poorly, failed to be sent. These are problems tied up in the problems of address that Lequeu's work partakes in, as well as the problems raised by his accusations. While his drawings engage the visual thematics, while the form of his presentation mimics the ways of framing material during the period, Lequeu does this all at a distance, on the margins, belatedly, and through his content, through his writing, through very subtle maneuvers and repetitions, through not so subtle maneuvers and repetitions, Lequeu resides within the architecture of knowledge of his age as a parasitic termite, weakening the structures within which he resides by consuming voraciously these various structures.

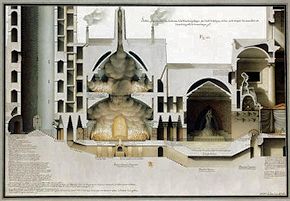

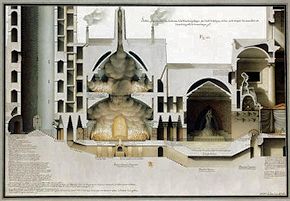

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Section perpendiculaire d'un souterrain de la maison gothique

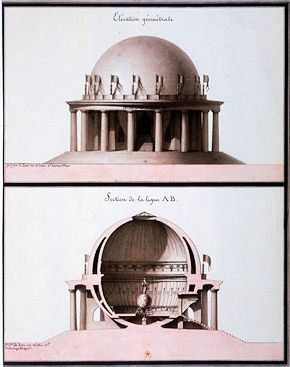

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Plan géométral d'un temple consacré à l'Egalité ; Pour le jardin du philosophe P***, 1794

|