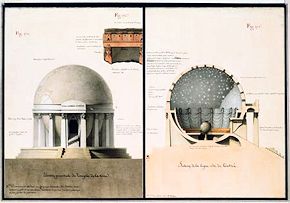

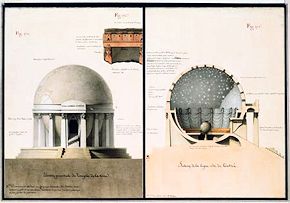

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Elévation géométrale du temple de la Terre

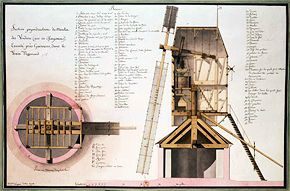

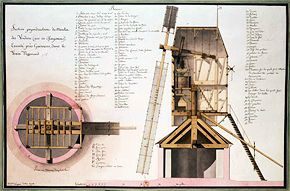

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Section perpendiculaire du moulin des Verdiers (avec des changemens [sic]), exécuté près Guiseniers, dans la Vexin Normand, 1778

Withdrawing/Undressing

In the process of with-drawing, Lequeu will address a withdrawal of the body that he perceives within and through the framing devices of his contemporaries, a withdrawal of desire posited by a new objectivity, a withdrawal that tries to cover over the body and desire, to cover up the desire in and of the body, in order to not (ex)pose how the body and desire have always been lost, incomplete, how desire is structured around this lack, and how desire and the body's lack are tied up together, even within the gaze of a new objectivity. Lequeu will posit a return to the body, an un-dressing of the body, but an un-dressing that does not carry a self back to an originary sight/site of plenitude, but to a site/sight of lack, of frustrated desire, desire that surrounds the body's lack. Lequeu will draw with desire to counter a withdrawal of desire, un-dressing a desire within this withdrawal, a desire to stave off loss, frustration. But the body always frustrates, its desires unsatisfied, unfulfilled. Lequeu will undress the body in order to (ex)pose the body as a site/sight of battle, where the lines are drawn, lines of desire, lines that desire to encircle the body, draw the body into a circle, a circle of knowledge, in order to with-draw one image of the body, an image of the body of desire, the sexual body, and replace it with a body of knowledge, a body of ideas, a body of ideals, a body of science, a body that can be known, a satisfactory body, a factory of production.

| |

In producing his imitation, but at a distance, Lequeu will repeat the gestures of scholar, by tracing out histories, drawing out histories with the body firmly drawn in, undressing elements of desire, of the sexual, un-dressing the distance of the scholar who tries to with-draw the body from study, her body from a study, un-dressing this distance as always being implicated in desire. Lequeu repeats the distancing gesture of a new objectivity, of a writer of the Encyclopédie, but he does this at a distance, in imitation, bringing the distancing voice of the scholar into intimate contact with the affairs of the body. To his drawings of maisons de campagne ou de plaisance, Lequeu adds this "scholarly" note on pleasure.

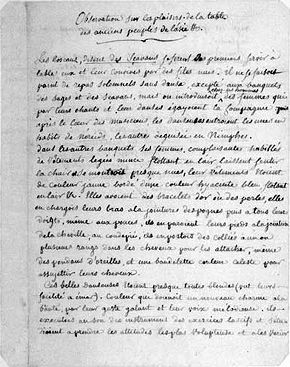

Observations on the Pleasures of the Table among the Ancient Peoples of Asia etc.

Scholars affirm that the Tuscans were among the first to have themselves and their guests served at table by naked girls. No solemn feasts- except those held by scholars and sages- were held without dancing, but (among those men) women were brought in to cheer the Company with songs and dances, and after the Choir of musicians, female dancers appeared, some in the costume of nereids, some disguised as Nymphs.

At other banquets amenable young women, clad in diaphanous garments that seemed to float on the air, so that one sensed their flesh, showed themselves almost naked. Their apparel was yellow in color, trimmed with hyacinth blue, floating on the air etc. They wore bracelets of gold or pearls on their arms and wrist joints, on their fingers and even thumbs, and on their ankles and insteps, as well as necklaces of the same in one or several strands to hold their hair, dangling ear-rings, and their hair in a sky-blue band.

These exquisite dancers were almost always fair-haired (because of their amorous nature). A hue that added a fresher charm to their beauty, through their amorous gestures and melodious voices. They performed lascivious motions to the sound of instruments and used all their art to achieve the most voluptuous postures which they varied to please the no doubt avid onlookers, all fired with pleasure's flame.

Such diversions were presented not only at banquets, but also on the public stage, where female Singers divested themselves of their garments and made free with the same languorous gestures and poses, and obscene words.

At refined parties, where there were no such dancers, the ladies attended the banquet modestly Dressed, but as the feast proceeded they began shedding their outer garments, and towards the end, all heated with the wine, they undressed completely: not only courtesans, but matrons and virgin maids did this in order to make themselves more agreeable and give more pleasure, although they still insisted upon all delicacy and propriety, of which they were extremely jealous.

It is a question of dressing and undressing, of shedding garments, of being heated, of getting heated, of becoming agreeable, a question of the feast, of eating, of eating the other. Lequeu is undressing the scholar, undressing the Encyclopédie. This is a question of affirmation. Scholars affirm. Moreover, scholars affirm what they know nothing about, for their banquets, the banquets of scholars and sages, involve no dancing, scholars and sages not knowing how to dance (and Nietzsche is never far away from Lequeu, the theme of dancing, of birds, of water, of song resounding in both their œuvre.).

Yet we may have to start from the title of this note. Lequeu states that it is a question about the pleasures of the table of among the Ancient people of Asia. However, Lequeu only writes about the Tuscans. This misdirection, mis-categorization plays throughout Lequeu's plates that claim to depict the buildings of all ages and all peoples. There is something more going on here than a simple case of mislabeling. Whether Lequeu intends it or not, (and this is precisely the case with Lequeu's work, a removal of all questions about intentionality, auto-biography, "Truth,") Lequeu's mislabeling undresses part of a process of addressing the other, of addressing the other in terms of the same, in terms the same does not wish to attribute to itself. Lequeu addresses this as a question of the East, of the manners of the East, the customs of the East, the exotic rituals of the East, and, yet, he talks about the West, about the "immorality," the drunkenness, the sexuality, the promiscuity of the West, an "immorality," drunkenness, sexuality, promiscuity, that the West would like to pass off as belonging to, being proper to the East. This will be a whole process of Romantic Orientalism that will be carried out in Delacroix, Ingres, Gerome, and others, and that has already been at work in the eighteenth-century. Lequeu, through mislabeling, whether he is aware of it or not, undresses this Orientalism as a displacement of characteristics that the West does not want to attribute to itself, a displacement onto the other of what resided in the same, a displacement that surrounds the (dis)avowal of the body.

| |

Moreover, Lequeu undresses a displacement within this displacement, undressing scholars' fascination with undressing, a fascination that is displaced by claiming that scholars and sages did not participate in these types of things. It is a question of distancing, of distancing what is least desirable about the self, the same, onto the other, of (dis)placing lack onto the other, of solidifying and marking out the boundaries between same and other. It is a process of trying to know oneself, of knowing what constitutes the same from the inside, and claiming to remain inside while stepping outside, claiming to know what lies beyond one's borders. It is a process of both undressing and withdrawing in the face of a nakedness that the scholar cannot keep her eyes off of, a question of knowing what cannot be known if her identity is to remain the same. This distance suggests a space of knowledge, a sight/site of knowledge, that remains outside of the space being studied, but the scholar is already there, too intimate with the materials at play, too intimate with the body, the sensual aspects of the scene/seen, a scene/seen to which the scholar remains at one level blind.

Lequeu (ex)poses this blindness, stages this blindness, a blindness of knowledge that is either feigned or withdrawn, and Lequeu (en)counters the withdrawal of the body by drawing the body into the scene/seen throughout his work. In this not(e) Lequeu repeats an emphasis on ornament, the feminine, the material, sound, and obscene that characterize many of his architectural and figural drawings. All the while Lequeu maintains an address with his age, this description of a refined party that ends in drunken, orgiastic revelry mirroring an account of an Ancient banquet staged by the artist Vigée-Lebrun. This movement, the movement of his far-fetched explanation, of imitation, but at a distance, a movement echoed by the lascivious movements of the dancers, the bacchic revelries, is part of a process of revelation that Lequeu repeats elsewhere, revelation in the sense that it allows insight by holding together in tension divergent elements of his culture, and revelation because it (ex)poses part of the procedural maneuvers of his age, maneuvers that with-draw the body, but a body that was never there in the first place.

Lequeu (en)counters this by drawing with the body, by discussing drawing the body, by imitating the steps of distancing, but always at a distance, always showing how a space of objectivity fails to be constructed, and can only be a construct, showing how a space of objectivity cannot with-draw the body, cannot disembody the eye/"I," the eye/"I" always embodied in a body that desires, that lacks, that lusts, that is sexual. In the Nouvelle Methode, Lequeu addresses and undresses the topic of drawing the undressed body. He writes,

However, although I ought not to enlarge the charming forms which contribute to the perfect beauty of the virginal body of the fair sex in all its nakedness, and so that no one may imagine that the nakedness of this living temple of our souls is the cause of licentiousness; I suggest that the charms of the unclothed female must, on the contrary, excite less lust than when she is clothed; it is true that if this were one of the beautiful bodies that Nature has created, then this nudity would at once strike the eye of the inexperienced draughtsmen who study its bewitching forms; but one quickly grows accustomed to all that, and one loses the coolness of chastity much faster than people imagine, however agreeable the attitude which it presents.

Again Lequeu imitates a thematics of morality, of the body as not sexual, the pure body as not inciting lust, a thematics of distance, of a studied distance. In fact, studying the undressed body, especially the undressed female body, like the banquets about undressing, really is not that exciting. Dressing is in some ways more exciting, more likely to cause desire, to allow for a play of desire, to allow for a fantasy of wholeness, of there not being a lack on the body of the Other, the impossible body of the Other. Really, there is nothing exciting about the naked body, and if one were before an example of a beautiful body of nature, the inexperienced draughtsman would be struck by the immediate presence of this naked body, the plenitude of this naked body. There would be no possibility for distance.

| |

All the while Lequeu writes this at a distance, to imitate a distance, a distance where again a question of agreeableness, of the sexually attractive, becomes not a question of reminding the viewer of her body, but of forgetting her body, both the body of the subject and the object of the gaze. Desire and lack are not an issue and are not at issue. With time there is distance, and the viewer transcends the body and forgets everything about the body. There is forgetfulness. The viewer becomes blind to the body, and, in becoming blind to the body is finally able to see the body, knowledge concerning the body always involving a certain blindness, a passage through questioning the blind Tiresisas, of the fatality of self-knowledge, of knowledge about one's own body, one's own image, of Narcissus. Lequeu, as with his note on table etiquette, reveals a certain blindness that is necessary for a gaze, at least the gaze being posited in Diderot and d'Alembert's work, to take place, a gaze that is not enmeshed with anxiety about lack. This is beneficial. If there were not this blindness, if one did not become blind after time, the naked body, when confronted, when presented before the gaze, would strike this gaze immediately, freeze this gaze, medusalize this gaze. Castration would occur. Better to be castrated from the start, to be a eunuch when gazing upon the female body.

The site/sight of drawing is riddled with dangers, dangers of looking, of being Acteonized, of the necessity for a certain blindness, but, for Lequeu, this blindness does not quite take place, opening up to another blindness, a blindness to the viewers implication within a network of gazes, of gazes that return a self all too quickly to the body, to the body as lack, the scene/seen of Acteon not quite lasting long enough. And yet always lasting. It is this tension, a tension between a disembodied gaze and a gaze that never leaves the body, that Lequeu is staging in his imitation of a type of objective gaze being offered by science, medicine, art, and the culture of the Encyclopédie, a gaze that replaces the body, a body that is a lack, that is always lacking, always missing, with an idea, a moral purpose, a moral purpose that always seems to repress a certain immorality within its own dynamics of looking, within its own origin, repressing its origin within the act of copulation, in the act of the copula, the "is" that allows this gaze to affirm what it "is" to be.

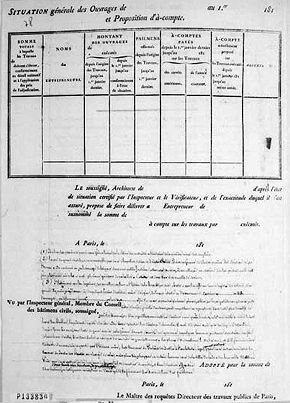

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Observations sur les plaisirs de la table des anciens peuples de l'Asie

| |

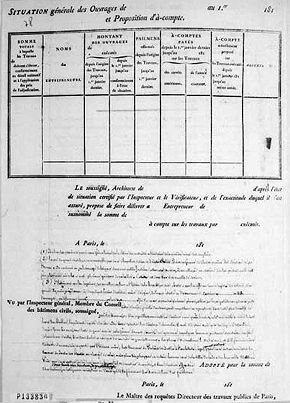

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Explication très forcée pour imiter aussi de ses compagnons d'arts, mais de bien loin, chacun faisant comme il lui plait son personnage industrieux

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Sommaire alphabétique des termes usités dans cet ouvrage

|