2013.12.23 19:47

23 December

I'm now wondering whether the above image of Castle Howard from Vitruvius Britannicus (published 1715-1725) somehow inspired the architecture of Piranesi as delineated within Il Campo Marzio (1762). Remember the...

I was prompted by the "what is experimental architecture" thread to look again at "Piranesi's Campo Marzio: An Experimental Design." After reading a few pages it became evident that the essay/project could be 'rewritten' to deliver a whole other set of results, a whole other 'history.'

By covertly publishing the Ichnographia in a second state was Piranesi himself conducting an experiment to see who would ultimately discover the two different plans?

Piranesi's language of the plans relates back to the origins of Rom(ulus and Remus) itself.

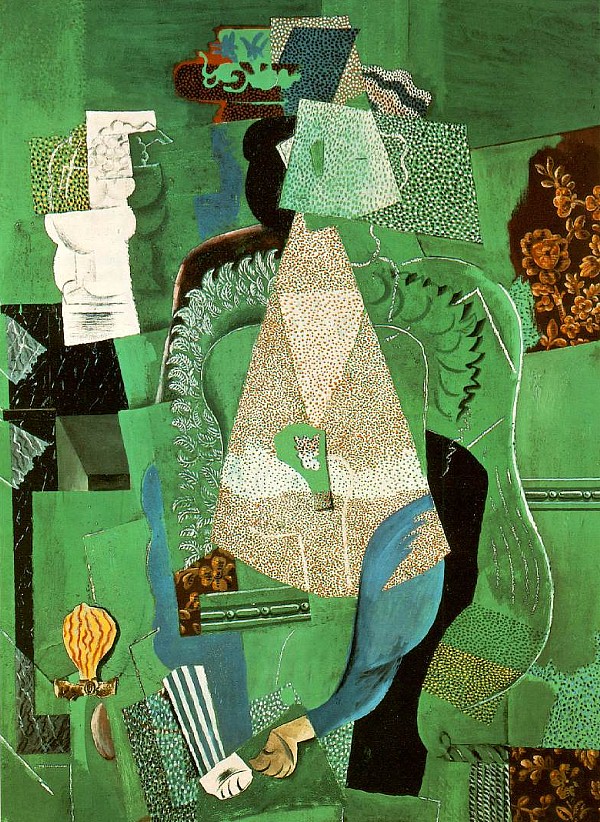

"Both Piranesi's Campo Marzio and Picasso's Dame au violon are "projects," though the former organizes an architectural dimension and the latter a human mode of behavior. Both use the technique of shock, even if Piranesi's etching adopts preformed historical material and Picasso's painting artificial material (just as later Duchamp, Hausmann and Schwitter were to do even more pointedly). Both discover the reality of a machine-universe: even if the eighteenth century urban project renders that universe as an abstraction and reacts to the discovery with terror, and the Picasso painting is conceived completely within this reality.

But more importantly, both Piranesi and Picasso, by means of the excess of truth acquired through their intensely critical formal elaborations, make "universal" a reality which could otherwise be considered completely particular."

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development, p. 90.

There is no Picasso painting with the title Dame au violon, but it is possible that Tafuri is referring to Portrait of a Girl (1914):

Project: redraw the Ichnographia Campus Martius following the principles of Picasso's (Synthetic) Cubism.

| |

2014.01.01 14:15

1 January

4711z

Tafuri's account of the operative tradition commenced with Giovanni Pietro Bellori's Le Vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni (The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects, 1672), in which he presents the "most important" artists of the time as a series of art-biographical accounts in the tradition of Vasari, introduced by a treatise on classical art. Tafuri describes the text as instrumental because Bellori's choice of the very best artists is limited by a set of values that he seeks to instill as lessons for artists and patrons of the present and future. Among Le Vite's twelve biographies are Annibali and Agostino Carracci, Caravaggio (but provisionally), Nicolas Poussin, Antoon van Dyck and Pieter Paul Rubens: the principal exponents of a "pure" classicism. The painters, sculptors and architects of the baroque fail to rate a mention, with Gianlorenzo Bernini, Borromini and Pietro da Cortona conspicuously absent. In promoting the classical tradition and setting aside the baroque as a forgettable interruption, Bellori's history sets up a dichotomy among his contemporaries, dividing them into heroes and reprobates. But more than this: in judging the present and recent part according to a preconceived idea of what the future should hold--the unconditional reinstatement of Renaissance classicism, in this case--Bellori, as Tafuri's archetypal operative historian, distorts his account of the past in order to shape the future, colouring the opinions of patrons spending money in the present. Bellori does not explicitly reject the baroque. He negates it, discounting its very existence. If his pretense of erasing from cultural memory that which actually happened--evidence, especially in Rome, being far from invisible--influences the future of art, then his historiography succeeds under the thesis against which Tafuri reads it. He 'does not take history for granted [nor] accept reality as it is,' writes Tafuri. The operative critic does not 'simply influence the course of history, but must also, and mainly, change it, because its approval or rejection have as much real value as the work of the artists.' Thus Tafuri distinguishes a more forgivable ignorance from operativity: an historian might write a biased account that reflects his or her social status, education, life experience, and so on; yet the instrumental historian's informed judgments precede the very selection of that which he or she represents as an account of the past, saying of that past which fails to conform to that figure's values: "it never happened. and nor should it ever". Historical authority therefore impinges upon the production of art at a grander instrumental level. While Tafuri cites Blear as an extreme case--and by doing so unambiguously casts Blear as a villain, a judgment that we also ought to regard as somewhat instrumental, not readily supported by later historiography--the endurance of baroque art indicates the relative power of the historian's authority. As a model, though, Bellori illustrates for Tafuri the complicity between historiographical distortions and the operative's capacity to imagine the future.

Andrew Leach, Manfredo Tafuri Choosing History (2007), pp. 122-23.

What are the "forgettable interruptions" of today's (operative) architectural 'history?' Who are the heroes and the reprobates of today's (operative) architectural 'history?'

What "preconceived idea of what the future should hold" does today's (operative) architectural 'history' espouse?

| |

2014.01.01 18:59

1 January

I like your answers, but they imply operative architectural practices more than operative architectural history, or, perhaps more precisely, architectural practice as operative architectural history. That's interesting, in that the architect acts as both practitioner and operative historian. I'm not sure how Tafuri relates to that (because I have to read further to understand more fully the whole operative criticism idea anyway), but your answers sure seem to put a contemporary twist on the subject.

2014.01.02 17:26

1 January

I know where my uncertainty comes from. Tafuri's argument against operative criticism is against architectural historians that (operatively) used history (incorrectly according to Tafuri) to set a (correct according to the historians) agenda for architecture's future. Your two answers have architects utilizing current operative socio-political 'histories' (not operative architectural histories) to form their respective agendas for architecture's present/future. That's not to say your answers are thus incorrect, just that there is a slight disconnect between your answers and where my question(s) came from.

Tafuri ultimately becomes clear as to how architectural historians should utilize history (the past) in their criticism of architecture's present/future, but he does not come to the same clarity as to how architects should utilize history (the past) in their architectural projects.

Koolhaas's and Schmacher's texts do comprise fairly pervasive (architectural) historiographic currents, so their respective architectural projects are not completely rely on (outside) socio-political operative histories.

Regarding sustainability/localization/critical regionalism it seems that those "projects" would naturally benefit from a critical focus on architecture's history (the past).

2014.01.02 20:04

1 January

t a m m u z, I agree that both "an operative utilization of architectural history as well as socio-cultural one" is present within the respective Koolhaas/OMA and Schumacher/ZHA 'projects'. Like I said in the beginning, I agree with your original answers, and I subsequently (oddly just I woke up this morning) came to realize how it was the "operative utilization of architectural history" that was missing. Anyway, between our last two posts the architectural and socio-cultural are now comfortably combined.

As a consequence of all of the above thread, I'm much more concerned/interested in how practice utilizes the architectural history/historiography. The type of architectural historian that Tafuri was against seems to no longer exist, and I'm not really sure who the correct (per Tafuri) architectural historians might even be today. The real 'operating' (historiography and practice) of today seems to be in the hands of architects themselves. (And whatever uncertainty I may still have is whether this assertion is true, and whether Tafuri ever anticipated such a development, but that's minor at this point).

Regarding Gehry, like you're now seeing the Seattle Library as critical regionalism (which sounds quite fine to me), I'm now interested in searching out "an operative utilization of architectural history" in his work. Gehry's early work does indeed comprise critical regionalism. And there's something about the initial designs (early 1990s) of the Disney Concert Hall's swooping forms/shapes first being conceived as stone that (I think perhaps) offers a key to the evolutionary unraveling of Gehry's operative utilization of architectural history. (These are very preliminary thoughts, and definitely nothing concrete).

| |

2014.01.15 19:51

15 January

...Tafuri teaches nonlinear history, its irreducibility into overly simplistic explanations--in whose name the universe of architectural discourse pretends to provide a presumed disciplinary autonomy; he teaches "knowing through signs and conjectures . . . not bases and certitudes." He teaches the intrisic contradictoriness of history, or rather, the coexistence of a multiplicity of tensions within it; but he also shows how such a system of contradictions--even the historian's procedure itself--far from dissolving into an infinite series of centerless motifs and discourses, are rooted in certain values. ...

Research and unease turn out to be one and the same, then, for those who manage to make their own the innate risk within a history that is really a construction--a project--rather than a simple reconstruction of events exactly as they happened.

Marco Biraghi, Project of Crisis: Manfredo Tafuri and Contemporary Architecture (2013), pp. 172-3, 175.

2014.01.19 19:25

19 January

Since its arrival on Friday, I've been spot-reading from ANY 25/26: Being Manfredo Tafuri (2000). Very early this morning I read Kurt Forster's "No Escape from History, No Reprieve from Utopia, No Nothing: An addio to the anxious historian Manfredo Tafuri," and one passage peaked my interest:

"Apart from Aldo Rossi and Carlo Aymonino, Tafuri proposed Vittorio De Feo's buildings and projects as "among the most remarkable of recent Italian work." What he gave in praise with one hand, he withdrew (dialectically) with the other, when he cautioned that "neither De Feo nor Manieri-Elia are able to link their choice of reference code to a suitable act of engagement." The projects and buildings of De Feo that Tafuri chose to illustrate are mostly megastructures resembling nothing so much as the contemporary American projects of a Kevin Roche or, later Arquitectonica."

I found it very odd that Forster relates the work of De Feo to that of Kevin Roche and (later) Arquitectonica, as he seems to have completely missed the connection of De Feo's work to that of The Philadelphia School. In any case, I now have to see exactly what it was that Tafuri wrote about De Feo:

"In writing about De Feo, Francesco Dal Co speaks of a "suspended architecture." And in fact, the works of De Feo--among the most remarkable of recent Italian work--oscillate between the creation of entirely virtual spaces and typological research at the level of the organism. The experimentation with the deformation of geometric elements is predominant, as seen in the project for the new House of Representatives in Rome, planned with the Stass group (1967); the Technical School at Terni (1968-74); and the competition for an Esso service station (1971). Here, De Feo treats geometry as a primary element, to be juxtaposed with the chosen functional order. Compared to the purism of Rossi, the architecture of De Feo, or for that matter of Georgio Ciucci and Mario Manieri-Elia, appears more empirical and casual. However, within its search for the pure and the intrinsic qualities of form, it possesses qualities at once self-critical and self-ironic, which are revealed as a disenchanted pop image (and wherein the exasperated geometric play of the Esso station is resolved). It is possible here to find a warning: once the "form is made free;" the geometric universe becomes an uncontrollable "adventure."* Without doubt, similar studies are historically born upon reflections on themes introduced by Kahn; yet, for Italians in particular, each study of linguistic tools loses the mystic aura and simple faith in the charismatic power of institutions. We are therefore faced with an apparent paradox. Those who concentrate on linguistic experimentation have lost the old illusions about the innovative powers of communication. Yet by accepting the relative independence of syntactic research, we are then confronted with the arbitrary qualities of the reference code. Thus neither De Feo nor Manieri-Elia are able to link their choice of reference code to a suitable act of engagement (which in itself may have other means of self-expression)."

Manfredo Tafuri, "L'Architecture dans le Boudoir: The language of criticism and the criticism of language") in Oppositions 3 (1974), pp. 46-48.

And the images presented along with this text are:

Regional offices competition, Trieste. Vittorio De Feo and Associates, architects, 1974.

Technical school, Terni. Vittorio De Feo and Errico Ascione, architects, 1968-74.

Esso Service Station, project, Vittorio De Feo and Associates, 1971.

|