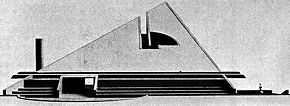

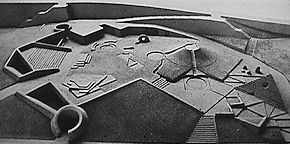

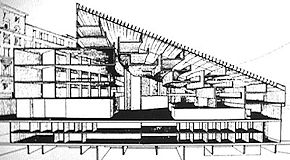

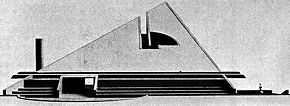

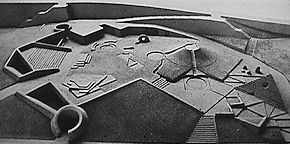

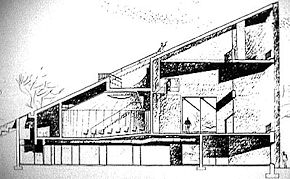

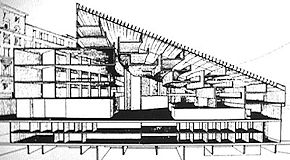

The Technical school, in particuler, owes a debt to Mitchell/Giurgola's Acadia National Park Headquarters Building (1965),

which, in turn, owes a debt to Kahn and Noguchi's Levy Memorial Playground (1963) and Kahn's Council of Islamic Ideology (1965).

Mitchell/Giurgola's Acadia National Park Headquarters Building was featured within (the Italian publication) Zodiac 17 (September 1967),

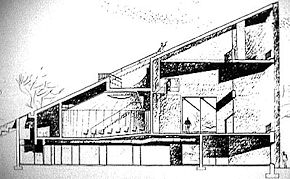

where the section drawing of the Acadia National Park Headquarters Building

bears a striking resemblence to a section drawing De Feo's new House of Representatives in Rome [actually the New Office Building for the Chamber of Deputies of the Italian Parliament], 1967.

| |

2014.01.25 15:15

25 January

Finished reading Manfredo Tafuri: Choosing History this morning, and Leach is quite a good analyst and writer. I'd like to relate two passages, one from the beginning and one from the end. On page seven: "Beginning his studies in October 1953, Tafuri faced the disconcerting reality that the University [of Rome] remained stocked with professors appointed under the Fascist regime. Over the duration of his diploma studies, he came to openly oppose several of these. His "hit-list" included Enrico Del Debbio, Ballio Morpurgo, Vincenzo Fasolo and, most explicitly, Saverio Muratori. He complained of their lack of interest in teaching, their distance from the classroom and their reliance on assistants to deliver the curriculum. He begrudged their prejudice against modern architecture: "The operative principal was that contemporary architecture must not enter the curriculum. It was considered a heresy." It thus is now easy to speculate that Tafuri specifically set out to "modernize" Fasolo's analysis of Piranesi's Campo Marzio. If such is the case, then Tafuri also just continued Fasolo's mistakes. On pages 269-270: "In "The loneliness of the Project", Groys argues that the work practices of artists, philosophers, writers, scientists, and so on assume a fundamentally existentialist stance in the relation to their project to the external conditions of day to day life. He conceives of the project as intellectual work that is isolated and independent; its manifestations represent the project, but remain distinct from it. The very notion of the project, as Groys portrays it, invokes a fine balance between a common scale of time shared by all and a temporal field inhabited by an artist. In each instance that an artist proposes a project--to an ethical panel, funding committee, gallery, etc.--he or she advances a scheme for the future. To begin the project is to commence the realization of that programme. Anchored not to the vicissitudes of the present world, their vision is imbued with critique, hope of the anticipation of consequence. It is thus fundamentally utopian, an expression of the need to surpass the present: 'each project in fast represents a draft for a particular view of the future, and each case can be fascinating and instructive.' Despite the completeness with which the artist might conceive of this future, from the outside one may simple engage with its "evidence"." Choosing to "build" a virtual museum of architecture is definitely a project.

2014.02.03 13:48

3 February

1994.02.03 death of Manfredo Tafuri.

Still in the process of reading Theories and History of Architecture (again). Now over a week ago, one of the illustrations collected toward the end of the book struck a new register of recognition.

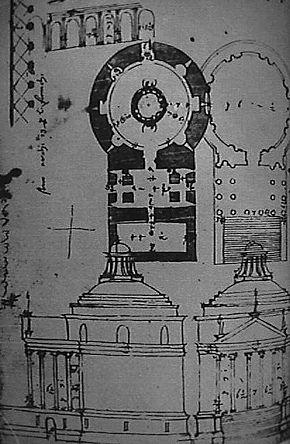

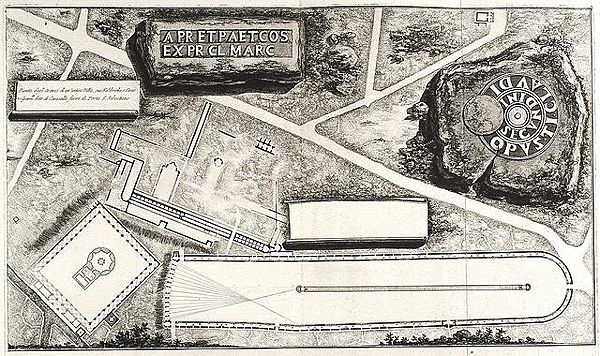

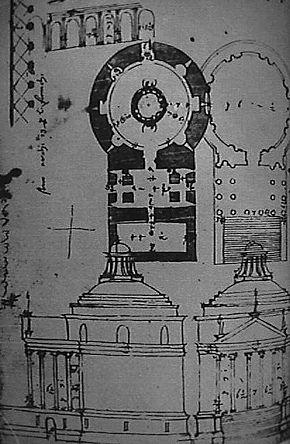

caption: Andrea Palladio, Existing and ideal reconstruction of the Romulus temple. R.I.B.A, London

This is the third illustration corresponding to Chapter 1: Modern Architecture and the Eclipse of History, and I'm sure I've seen the image many times before (since I've owned a copy of the book since 1980), but never before did it register any significance for me. There is no explicit reference to the Palladio reconstruction drawing within Chapter 1, and the only possible reason for the inclusion of the illustration lies within a passage from page 19:

"One of the main features of Borromini's architecture is that he sees himself as the heir of the troubled Mannerist issues, of their uneasy symbolic world, of their ethical criticism. It is for this very reason that Borromini gives first place to the problem of history. For Borromini, architecture must not follow a programme imposed from outside, but has to find its own motives in the independent shaping of its programmes, must fold on itself to show its structure as a renewed instrument of communication, has to stratify itself in a complex system of images and geometric-symbolic matrixes. Therefore the spatial synthesis that will unify such a tangle of problems van only tend to a multi-valence and to a simultaneity of meanings. In the typological syntheses constantly adopted by Borromini as a method of configuring space, there always seeps through a bricolage of modulations, of memories, of objects derived from Classical Antiquity, from Late Antiqity, from Paleo-Christian, from Gothic, from Albertian and utopistic-romantic Humanism, from the most varied models of sixteenth-century architecture. They span from the spatial permeations of Perruzi to the anamorphic contractions of Michelangelo and Montano, to the anthropomorphic decorativism of Pelligrini, to the attempts at linguistic renewal by Vignola and Palladio."

| |

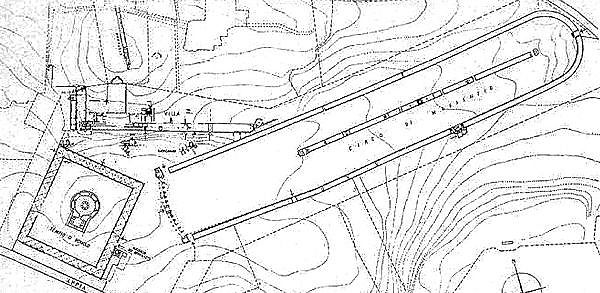

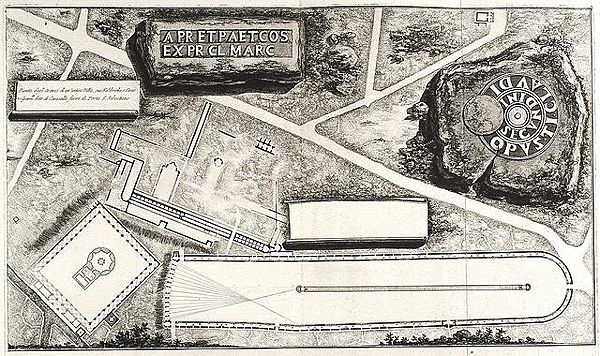

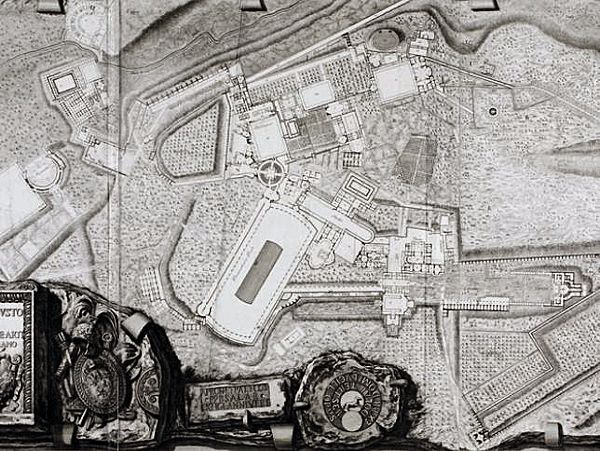

Palladio's reconstution is of the temple that once stood atop the mausoleum of Romulus (son of Maxentius), which forms part of the Imperial (munus) complex along the Appian Way.

Thanks to Palladio's drawing, I can more accuratly draw the plan of the mausoleum/temple. The plan I had been using (from an image found online) was not clear enough to make a definitive rendition of the plan.

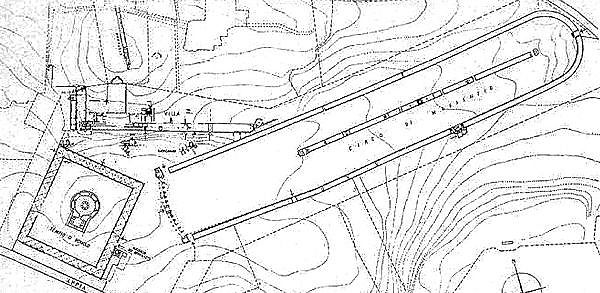

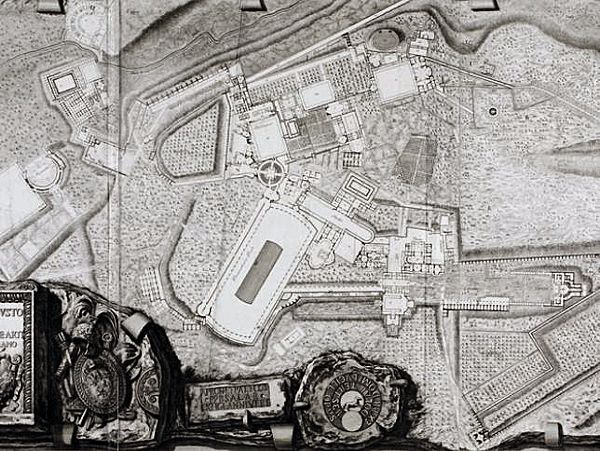

Coincidentally, and now also over a week ago, I found a detailed eighteenth-century engraving of the Maxentian complex plan, incorrectly placed within a wiki collection of G.B. Piranesi's images from Le antichit� Romane:

Since this engraving is not by Piranesi, it is difficult to discern who the real engraver is. My guess it that it is by Piranesi's son, Francesco, based on the engravings similarity to Francesco's plan of Hadrian's Villa.

On 3 February 1544, the sarcophagus of Maria was discovered (very likely while the old basilica was being demolished to make way for the new/present one). The sarcophagus of Maria may well be the last substantial imperial artifact of (the city of) Rome, and after an illustrious title page and a frontispiece, it is an image of the sarcophagus of Maria that Piranesi uses to begin his Campo Marzio publication. In a most elegantly covert way, Piranesi began the 'history' of the Campo Marzio with what is really it's ending, and what is probably the world's greatest designed architectural inversionary double theater goes on from there. But there is a strange fabrication going on there too.

...my theory/methodology is best described as appositional.

Architecture reenacts human imagination, and human imagination reenacts the way the human body is and operates. The human body and the design thereof is THE enactment. The human imagination then reenacts corporal morphology and physiology, and architecture then reenacts our reenacting imaginations.

I can still remember how it was difficult (for me) to find a definition of bricolage back in the late 1970's. It's not at all difficult now, however:

"In the practical arts and the fine arts, bricolage (French for "tinkering") is the construction or creation of a work from a diverse range of things that happen to be available, or a work created by such a process. The term bricolage has also been used in many other fields, including intellectual pursuits, education, computer software, and business."

"Bricolage is considered the jumbled effect produced by the close proximity of buildings from different periods and in different architectural styles. It is also a term that is admiringly applied to the architectural work of Le Corbusier, by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter in their book Collage City, suggesting that he assembled ideas from found objects of the history of architecture. This, in contrast to someone like Mies van der Rohe, whom they called a "hedgehog", for being overly focused on a narrow concept."

While appositions are not always bricolage, it might well be true thought, that bricolage is always a form of apposition.

| |

2014.02.13 21:55

13 February

"By that time I had begun to understand architecture, and we were ready to stage the first faculty occupation of the department. There had been earlier demonstrations all over Italy. In any case, the first was in 1958. It was deeply flawed, because our pretext for demonstrating was the introduction of the state exam for architects. We were a bit cynical, and we thought we needed to come up with arguments that would stir our ignorant colleagues to action, to stage something that would violently shake up the entire department.

The most important thing is that we were looking for pretexts, weak links in a chain, in order to effect disruption. We used to say that we had a little bit of the whole world concentrated within the department. But that whole world was conceived, as Antonio Cederna taught, as a protest against corrupt building practices from which emerged a political comprehension of the situation. All of us followed the trial of Salvatore Rebecchini/L'Espresso with tremendous anxiety, not least because it was our bible. And we found that we had in front of us at a certain point Saverio Muratori, a figure who taught fourth- and fifth-year design studios. He had just arrrived in Rome from Venice, and was a well known personality. Muratori was the architect of the Christian Democrat office at the EUR. He was someone unique, someone who had strong intellectual resonance, someone who could really think. He proposed a rather tragic vision of history, because for him the crisis began at least inthe 18th century. It seemed like one didn't need to think so much about [Hans] Sedlmayer, but rather about someone who had contemplated the crises in isolation and suffered considerably; suffered for the world. These crises seemed to be the crises of European science, of Husserl. Muratori, advocating an extreme reductive culture, was against everything that was modern. This is the point. He thought that true modernity meant that everything should start all over again. This was a facinating point of view.

We could not allow ourselves to think about these things because they were minor in relation to certain much larger problems. But Muratori was the person we wanted to confront because he was invulnerable. He refused to talk with us because his way of thinking only functioned if it remained closed to dialogue. At this point he realized that he was just another weak link, so we organized the operative concept of "libera d'insegnamento" [freedom of teaching]. And then there also had to be "freedom of learning.""

Manfredo Tafuri, "History as Project: An Interview with Manfredo Tafuri" (1992).

2014.02.17 18:34

17 February

It might just be worthwhile to reread what Kahn said about the Pantheon with respect to the Parliament Building design and with respect to Coarelli's theory that the Pantheon marks the spot of Romulus' "ascension into godhood" (hence the oculus). Plus Tafuri's many citings of Kahn within Theories and History of Architecture and Biraghi's "Kahn as Destroyer" come into play as well.

|