| |

72

Site: The Fictional Present

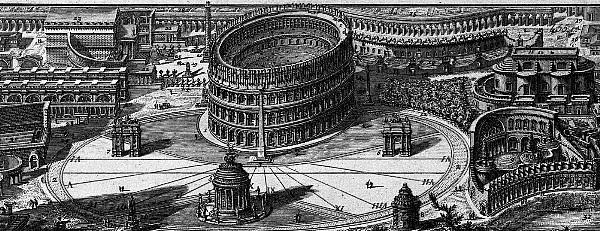

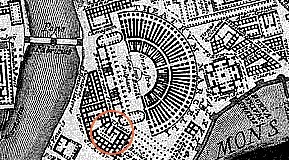

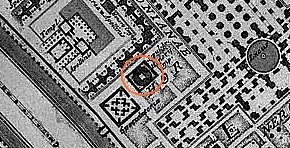

Now let us, by a flight of imagination, suppose that Rome is not a human habitation but a psychical entity with a similarly long and copious past--an entity, that is to say, in which nothing which has once come into existence will have passed away and all the earlier phases of development continue to exist alongside the latest one. This would mean that in Rome the palaces of the Caesars and the Septizonium of Septimius would still be rising to their old height on the Palatine and that castle of S. Angelo would still be carrying on its battlements the beautiful statues which graced it until the siege of the goths, and so on. But more than this. In the place occupied by the Palazzo Cafferelli would once more stand--without the Palazzo having been removed--the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus; and this not only in the latest shape, as the Romans of the Empire saw it, but also in its earliest one, when it still showed Etruscan forms and was ornamented with terra-cotta antefixes.

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontents, 1930.

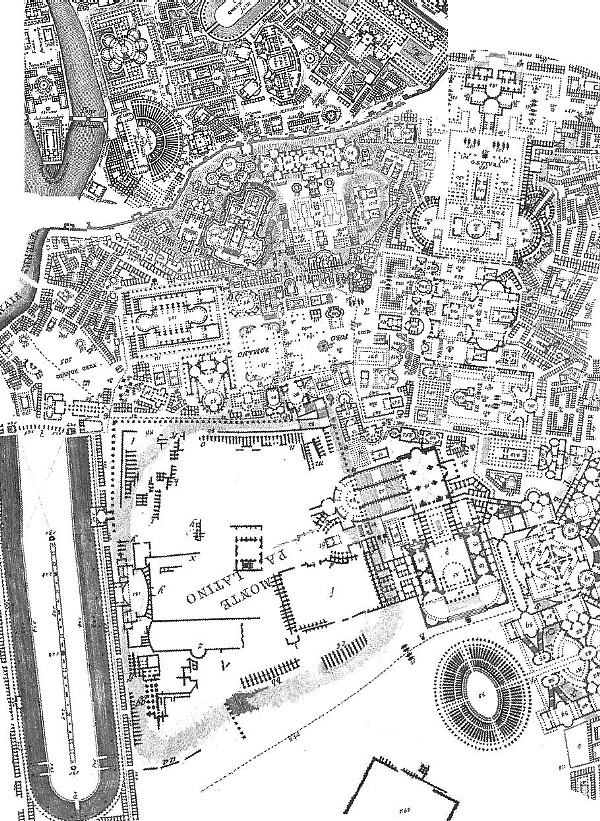

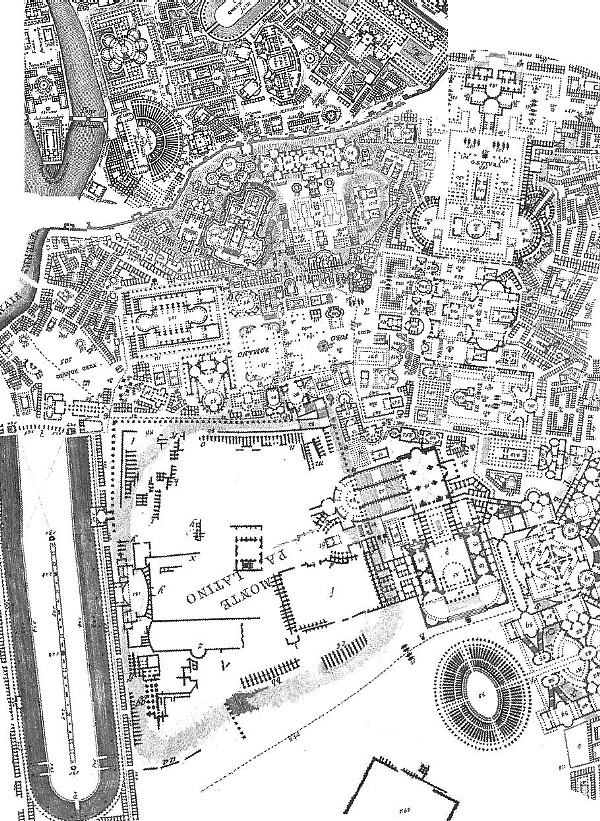

The problem of site is fundamental to Piranesi's project. "Before treating off the works of the Campo Marzio," he notes, "it must be said what place it was located, and what was its extent in ancient times." he defers here to the authority of classical texts: The Campo Marzio, therefore, according to these witnesses, was that level ground [pianura] of the City between the hills and the Tiber, situated at one time outside the walls."6 From here follow descriptions of the grandeur of the Campo Marzio and of its architecture. But what motives Piranesi in his choice of site? Why, in a project devoted to reconstructing ancient Rome, has he ignored the historical, monumental center of Rome, where the existing ruins were concentrated and stood more or less free of contemporary building? Certainly, in other volumes, such as the Antichitŕ romane, he had already described these monuments, but this still fails to explain the inordinate space given over to the Campo Marzio; nor in the other works do we find the topographic and planimetric preoccupations that characterize the Campo Marzio. What, then, is the basis for Piranesi's interest in this (literally) marginal zone, "outside of the city walls"? And, paradoxically, if this site is marginal with respect to ancient Rome, it coincides with the most densely built and crowded area of contemporary eighteenth-century Rome: the lowland marshes where, since the fall of imperial Rome, a crowded medieval city had grown up.

6G. B. Piranesi, Campus Martius antiquae Urbis (Rome, 1762); reprinted, with an introduction by Franco Borsi, as Il Campo Marzio dell'antica Roma (Florence: Colombo Ristampe, 1972), chap. 1, p. 3. It should be noted that the volume in which the project for the Campo Marzio is published is something of a mixed bag. Piranesi apparently began the large site plan, the grande pianta, in 1757. John Wilton-Ely suggests that the Campo Marzio should be understood as the final (fifth) volume of Le antichitŕ romane (Rome, 1756), and should thus be seen in continuity with the earlier archaeological investigations (Wilton-Ely, The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi [London: Thames and Hudson, 1978], 73). Like the earlier volumes, the Campo Marzio contains historical texts, reconstructed plans, and views of the "raw material"--the ruins, often with later accretions stripped away. But the detail and elaboration of the site plan, as well as the sequential maps of the historical development of this zone are all unique to this volume. Therefore, in this case, it makes sense to speak of the "project" for the Campo Marzio

| |

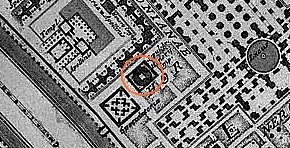

Similarly, the T[emplum] Pietatis and the Theatrum Marcelli are delineated together within the Ichnographia, yet the temple of Pietas was destroyed by Augustus in order to make room for the theater of Marcellus.

| |

|

Of more interest, however, is that Piranesi also omitted buildings that should have been delineated within the Ichnographia. While the Sepulchrum Honorij Imp., the mausoleum built by the emperor Honorius circa 400, is within the Ichnographia, the building that the mausoleum was in actuality attached to, the basilica of St. Peter built by the emperor Constantine circa 330, is not delineated within the Ichnographia.

| |

|

To: James Adam

From: Robert Adam

Date: 13 September 1755

[I] got [Piranesi] to finish the whole of Rome and to publish it alone without joining it in a book whose principal dedication was to my Lord Charlemont, which made mine less regarded, whereas mine being sold separate all the world will purchase it and have no other name to detract from the honour of the intention.

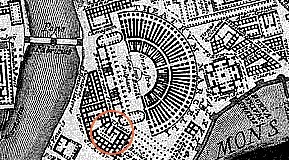

Within the first volume of Le Antichitŕ Romane are a series of plans of ancient Rome: baths of Titus, topographical map, barracks of Tiberius, baths of Caracalla, nymphaeum of Nero, baths of Diocletian, Forum Romanum, Capitoline Hill. When combined with the Ichnographia Campus Martius these plans constitute an almost complete plan of ancient Rome.

|