| |

75

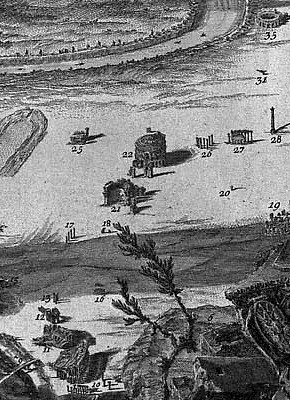

If the site plan is the result of an inversion, the city having been folded back upon itself, something analogous happens in Piranesi's representation of time. A second clue appears in a plate entitled Scenographia Campii Martii. The use of a theatrical term here is not insignificant. It inscribes this view within the whole problematic of Piranesi's relation to the theater and to scene design. But, paradoxically, this image, by the criteria of the traditional scena per angolo with which Piranesi is often identified, has none of the conventional scenographic elements or illusions. The point of view is from above; the horizon is excluded. The ruined fragments, covered with hieroglyphics, occupy the frontal plane and establish a barrier to the view of the site itself, marking out precisely on the image that they frame the extent of the Campo Marzio as it is rendered on the large plan.

Piranesi depicts the monuments themselves in ruins, indicated by trace or fragment. He accurately shows their locations and the surrounding topography, establishing a correspondence to the actual condition of the ruins in the mod-eighteenth century. In this way Piranesi's drawing acknowledges the passage of history. But the fiction of the drawing is to present these objects shorn from their actual context, as if the intervening years had passes without the occupation and transformation of this part of Rome, as if the level of the terrain had not risen, burying the colonnades up to their capitals. The Stadium of Domitian, for example, is indicated by a track in the earth and a solitary structural bay, the remains, perhaps, of the imperial box. Its figure is preserved, empty, in denial that a medieval town had grown up precisely in this area, that the form of the circus, while still preserved, exists as a densely built urban space created by the churches and houses constructed over the ruins of the stadium.

This selective erasure of history has a parallel in certain of Piranesi's vedute, where he repeats this operation by dismantling subsequent construction and presenting the view of the ancient structure as a spectral ruin9 This makes clear a fundamental ambivalence in Piranesi: the simultaneous negation and affirmation of the value of history.

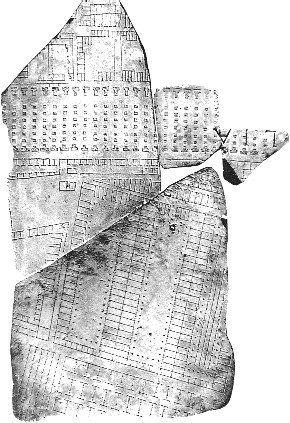

But, further, the equivalence established between the piled-up fragments in the foreground and the ruins on the site seems to undercut the importance of topography and precise location. Within the compressed space of the foreground, each fragment represents, through a metonymic operation, and entire monument, ready to be moved into place on the almost tabula rasa in the background. In this sense, Tafuri's characterization of the Campo Marzio as "a formless heap of fragments" does not seem exaggerated. And the actual displacement of monuments may be verified by comparing the Campo Marzio with the Severan marble plan of Rome. 10

76

5. Piranesi, Scenographia Campi Martii (aerial panorama of the Campo Marzio). Plate from the Campo Marzio.

The Scenographia signals the procedure of doubt to which Piranesi subjects the raw data. His is a violent act of distancing the project from the real historical continuity of Rome in order to reinvent that history. In ideological terms, this operation is highly ambivalent , in as much as it engages in the very manipulations it seeks to criticize. With history and memory brought into play in this equivocal manner, we are left to wonder, given the fiction of the starting point, whether the subsequent moves can be any less contingent.

9Plate XLIII, for example, is a view of the Tomb of Hadrian (later the Castel Sant'Angelo), depicted as though it had fallen into ruin and no further building had taken place.

10For example, Piranesi has accurately reproduced the Septa Julia from the fragment of the Severan marble plan (the forma urbis), but has relocated it to a site adjacent to the Servian wall. He has translated the figure of the septa to a site along the Via Lata and then accommodated the site to the idiosyncrasies of the figure represented in the marble plan. Other transpositions and departures are noted in the commentaries on the Campo Marzio in G. B. Piranesi: Drawings and Etchings at Columbia University, exhibition catalogue, ed. D. Nyberg (New York: Avery Architectural Library, 1972); Michael McCarthy, in "The Theoretical Imagination in Piranesi's Shaping of Architectural Reality," Impulse 13, no. 1 (1986-87), charts in detail Piranesi's "misreadings" of the archaeological record in the case of the tomb of Cecilia Metella.

| |

2013.12.28

It has always been my impression that Piranesi's Scenographia of the Campo Marzio is a perspicacious demonstration of how little actually remains of the ancient Roman architecture that once stood within the Campus Martius.

The Scenographia depiction of the 40 existent in situ architectural remains of the Campo Marzio is in stark contrast to the Catalogo list of 322 buildings mentioned by ancient authors to have once existed within the Campo Marzio.

2002.02.20 11:29

Re: paper architectures

B.'s wondering about text (on paper, etc.) architectures makes me want to relate something I found out about the architecture of ancient Rome (particularly the Campo Marzio). An index at the end of Piranesi's Il Campo Marzio publication entitled "Catalogo" lists all the buildings known to have existed in the ancient Campus Martius, and the name of each building is accompanied by the literary (i.e., textual) references within ancient writings where mention of the respective buildings occurs. What is interesting is that eventually I learned (via long assimilation, if not also osmosis) that the only 'real' evidence left of many ancient Roman buildings is their mention in texts. Even within today's archaeology there are no physical remains for lots of 'known' ancient Roman buildings. Of course, there is apparently a lot still buried under later buildings, but one can still (now) think of much of today's 'paper architectures' as the inverse reflection (in a 'quondam' mirror?) of much of ancient Rome's architectures.

A "formless heap of fragments" is what went into making the Ichnographia Campus Martius, not the Ichnographia itself.

1998.01.07

Points of Departure

...Piranesi's cribbing of the Porticus Aemilia for the Septa Julia may actually represent Piranesi's scale for the entire Ichnographia. It could be that Piranesi very purposefully installed the Forma Urbis fragment of the Porticus Aemilia into the Ichnographia for the precise purpose of demonstrating more of the actual scale (and gigantism) of ancient Rome (--it is as if Piranesi is here illustrating his own quote about how one just has to look around at Rome and Hadrian's Villa to see the examples he emulates.) Piranesi was not being deceptive or misleading, nor was he acting out of ignorance of the fragment's true identity. Piranesi used the Porticus Aemilia as evidence and example.

|