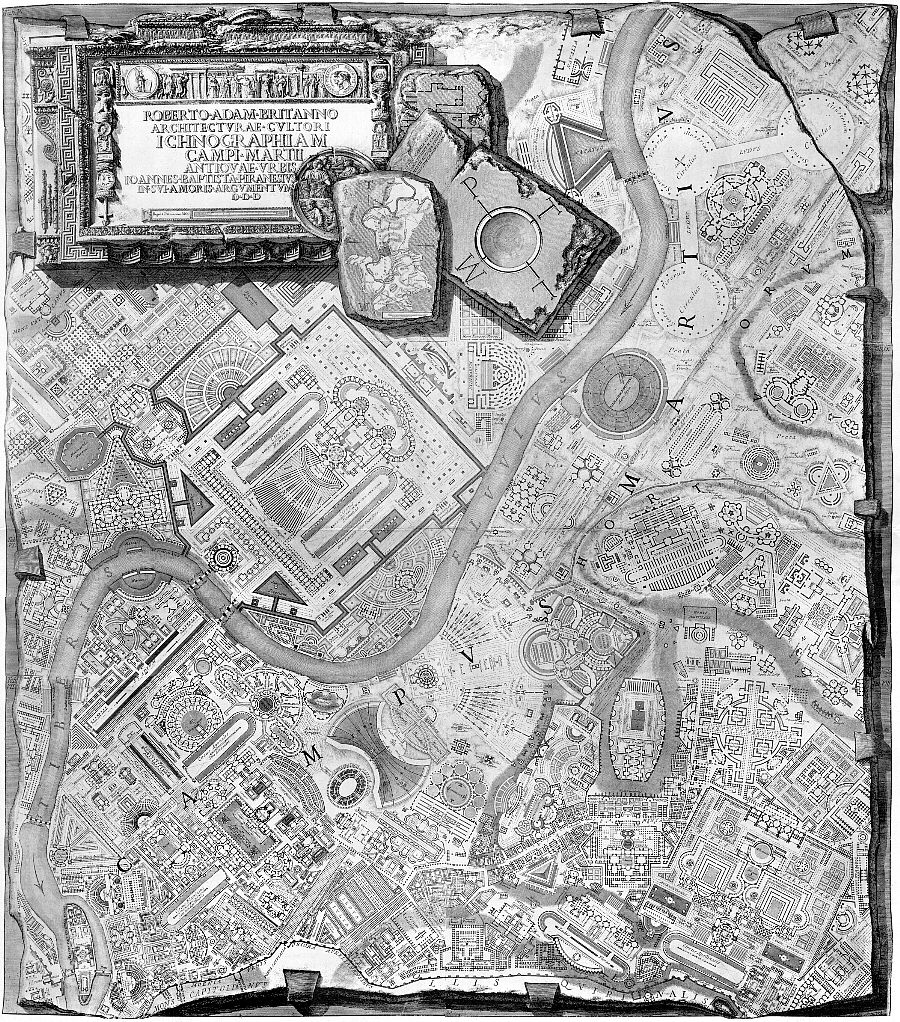

On this great page, one can say, the attention of scholars has always been completely distracted, and only the chronological ordering of the Piranesian opus revealed the dense dedicative frontispiece: Roberto Adam - britannico architecturae - cultori Ichnographiam Campi Martii antiquae Urbis - Johannes Baptista Piranesius - in sui amoris argomentatum.

There is nothing archeological in this plan. Only the curve of the Tiber and some generic indication tells us that the place is Rome. The designation of places appear here and there: "Horti Salustani", "Horti Luciliani", "Horti Neroniani", "Bustum Caesaris Augusti" and "Area Marti"; "Horti prius pompeiani dein Marci Antoni", "Forum M. Aureli", "Circus Agonalis sive Alexandri", "Horti Getae", "Horti Domitiae", which recall to us the Roman topography but for which our current knowledge can find no adequate correlation.

Archeological knowledge in Piranesi's time was just beginning. There was great interest in antiquities, but certain denominations, attributions, locations of monuments, were based only and prevalently on literary sources: the topographic inaccuracies should then not surprise us.

It is surprising, however, that monumental elements whose location, if not denomination, was certain, were subordinated, or moved, or in any case made the base for systemizations that are out of proportion to the spaces actually available or estimated in their original state by the expert eye of the architect.

Of the above we will shortly give an account, as we make an appraisal of the spirit and finality of the Piranesian creation through his Campomarzio. Which reveals to us, in the meantime, a mature knowledge in contact with the antique world and an intuition for how life was lived in the imperial city, its character, albeit somewhat exalted by admiration.

Piranesi captures the solemnity of the public buildings that are representative of public life: the forums, the sacred places of the Gods, the places consecrated to the memory of the emperors, the tombs.

He perceives that ancient Rome intertwined with the green areas of villas and gardens, and he inserts even in the heart of his designed city the arcades, the "promenades", and bodies of water, and fountains, and "swimming areas", and "places for mock naval battles"; in it he places the utilitarian and military buildings. His conception of the functionality of the ancient city based on literary and historical sources is thus a complete one, and not out of proportion, albeit poetically envisioned, to the reality that must have been the city at the end of the Empire.

How all this is composed into a building plan can be seen in the illustrations connected to this text. A more thorough examination will bring us further into the argument proposed at the beginning of the present considerations: that is, it reveals to us the quality of the architect.

More than a reconstruction with archeological intentions, this image of Rome is nothing if not a venting of architectural invention, stemming from an evident need to create.

All of the qualities that characterize the architect are manifested here, especially the ability to compose great complexes within fundamental regulating lines, which give unity to the variety of different orientations. In the complexes that are more tied to actual conditions and the knowledge, albeit limited, of existing archeological datums, the reconstruction (or recomposition), going beyond strictness and approximation towards historic reality, reveals original spatial connections and a resource of new and original forms, even with respect to the Roman typology.

These compositions, furthermore, bearing pseudo-archeological indications, assume an inventive character for solutions in which references to Roman characteristics are diluted or disappear, giving place to a unique architectural typology.

The great regulating lines typical of the Romans are amplified and are made the basis for complex frameworks to which are tied groups of constructions of exceptional form, which have no correlation to other realizations in the contemporary field of practice nor precedent, and, more importantly, anticipate conceptions which will later have major development. Precisely in these lines one grasps the introduction of an architectural personality.

| |

Fasolo's statement regarding the Ichnographia's lack of "archeology" was echoed when Tafuri said "the archeological mask of Piranesi's Campo Marzio fools no one." Tafuri goes on to say the Ichnograpia "is an experimental design and the city, therefore, remains an unknown."

Both Fasolo and Tafuri are here wrong. Anyone that has read Piranesi's Il Campo Marzio texts, (including the indexed evidence of 312 ruins within the Campo Marzio and the approximately 1000 literary references to 323 individual buildings, gardens, arches, obelisks, sepulchers, etc.), and redrawn the plan wall for wall and column for column will resolutely testify that Piranesi's Campo Marzio is not only a knowable city, but also an exceptional representation of Rome's Campo Marzio from Romulus to Honorius.

A fair share of the plans within the Ichnographia bear Piranesi's signature, of that there is no doubt. Remaining largely unrecognized, however, are the strict parameters within which Piranesi manifests his creativity, and even his "new ideas" aim to deliver clearer notions of the Imperial capital and its unique urban (design) narrative.

"Authenticity is one thing, veracity another."

--Marguerite Yourcenar

Fasolo here brings to mind the ideas regarding the philosophy of history found in Giambattista Vico's Scienza nuova.

"[V]ico was led to stress the differences rather than the analogies between historical and other forms of inquiry and laid emphasis upon the need for the historian to recreate imaginatively the spirit of the past ages and the outlook and attitudes of mind possessed by the men who lived in them, instead of trying to impose upon them inappropriate interpretive models--"Pseudomyths"--suggested by ways of thinking and feeling current in his own time."

--Patrick L. Gardiner

The ancient Campo Marzio (Fields of Mars), although a viable part of the city since the time Augustus (27 BC-14 AD), remained outside the Servian walls of the city proper, that is, until the time of Marcus Aurelius (169-177 AD) and his building of the Aurelian Wall which emcompassed the capital's entire built up area. Thus, since its beginnings, the Campo Marzio accommodated sub-urban activities, specifically military exercises in connection to Mars (the god of war) and the general burial of the dead in compliance with the Roman custom of interment outside the city walls. The proliferation of stadia and circusus, moreover, accommodated the growing demand for public spectacle and "entertainment," and the surrounding open country side naturally gave way to the gardens and estates of the aristocracy and the wealthy.

The individual plans within the Ichnographia depict all the Campus Martius structures once built, from the altar of Mars erected by Romulus to the Sepulcher of Empress Maria, wife of Honorius.

As to his "quality" as architect, is it not possible to consider Piranesi virtually among the very best of Imperial Rome's architects?

|