Encyclopedia Ichnographica

| Tafuri, Manfredo

| 6/6

|

It rocked Eisenman in his chair...

2005.11.10 10:38

My opinion of Bloomer's book, as far as it relates specifically to reading Piranesi's Ichnographia of the Campo Marzio, is that it is indeed wrong and [somewhat] trite--almost all of what Bloomer writes about the Ichnographia is taken virtually verbatim from Tafuri; she does, however, include some original material relative to the "pit of the underworld" citing it as the entry way into understanding the Ichnographia as a labyrinth, but she misses the real key to the large plan (the tiny intercourse building) which is directly across the Tiber from the pit. Bloomer's book may be fun, but it is not good scholarship in that she really did not come to read and understand the whole plan at all--she went on to seek meaning "underneath" the plan while what she really did was avoid the actual plan itself. Can you honestly say that you now know what the Ichnographia is about after reading Bloomer's book?

It rocked Eisenman in his chair...

2005.11.10 15:03

To be honest, I care very little about what Bloomer wrote or how she intellectually operates. What I do care about is what Piranesi delineated via the two versions of the Ichnographia of Il Campo Marzio.... All I have ever done is analyze the Ichnographia itself, which is exactly what virtually all other contemporary writers on the Ichnographia have not done! I have never been interested in spreading some current/trendy intellectual "thought" by troping Piranesi and the Ichnographia, a course of action begun by Tafuri. What I am interested in is to find out what Piranesi did himself.

Eisenman was rocked in his socks!

2005.11.15 13:17

[Eisenman] mentions in "The Wicked Critic" (2000) that "This document [the Ichnographia], then, is a useful example for Tafuri for two principal reasons: first, in his montage of actual buildings, fantasy buildings, and buildings moved from their actual site..." It's worthwhile noting that no where does Tafuri ever mention that some buildings within the Ichnographia are moved from their actual site, yet within the Encyclopedia Ichnographica as published at www.quondam.com 1998-2000 there is much note of buildings within the Ichnographia that Piranesi moved from their actual site. Moreover, that Piranesi moved some buildings from their actual site is indeed part of the original material within the analysis of the Ichnographia at www.quondam.com.

| |

UPenn M.Arch Summer Reading List

2006.06.15 13:30

Using the Kwinter quotation, "the effect of unforeseeable complexity that arises from multiple interfering structures blindly pursuing their own clockwork logic," as a case in point, one only has to compare it to the following Tafuri quotation, "The clash of the formal organisms, immersed in a sea of formal fragments, dissolves even the remotest memory of the city as a place of Form, and the whole organism seems to be a clockwork mechanism."

| |

Theory Part II - Doing What I Said I Would Do...

2007.03.28 15:18

If anyone here thinks that I am opposed to or think lowly of "getting ideas from misreading a text," then you have jumped to a wrong conclusion.

What I do find fault in is Tafuri's interpretation of Piranesi's Campo Marzio. And since this faulty interpretation is a crucial element of Tafuri's "historical-critical project"/research, I then see the need to re-evaluate Tafuri's overall theory. Moreover, that what Piranesi actually did with the Campo Marzio is indeed the opposite of Tafuri's interpretation of what Piranesi did with the Campo Marzio can well suggest that Piranesi's Campo Marzio shouldn't even be within Tafuri's overall theory.

And then there is Peter Eisenman utilizing and teaching Piranesi's Campo Marzio based on (really just repeating) Tafuri's misinterpretation of Piranesi's Campo Marzio. Furthermore, Eisenman has not contributed any new insight regarding Piranesi's Campo Marzio, and, if anything, more just tailors Tafuri's misinterpretation to suit his own design methodology. What I see fault in here is Eisenman's suggestion that his method is based on what Piranesi did within the Campo Marzio, where, in fact, Eisenman's method is based on Tafuri's misinterpretation of what Piranesi did. Again, it is more the case that what Piranesi did within the Campo Marzio has very little to do with Eisenman's method.

Theory Part II - Doing What I Said I Would Do...

2007.03.28 16:17

Eisenman doesn't misread Tafuri at all. And judging by Tafuri's interpretation, he didn't even bother to read Piranesi's Latin labels within the Ichnographia Campi Martii. Misreading [Piranesi] isn't even the issue here. It's more the lack of reading [Piranesi] altogether.

2016.11.11 09:54

7 November

"...remember that the problematic of allegories, and even of parables, is that what they allegorize is always viewed retrospectively, the fable or allegorical narrative coming after an experience or theme that is conveyed by the subsequent performance, so to speak, in a different, more attenuated, and coded form."

Said

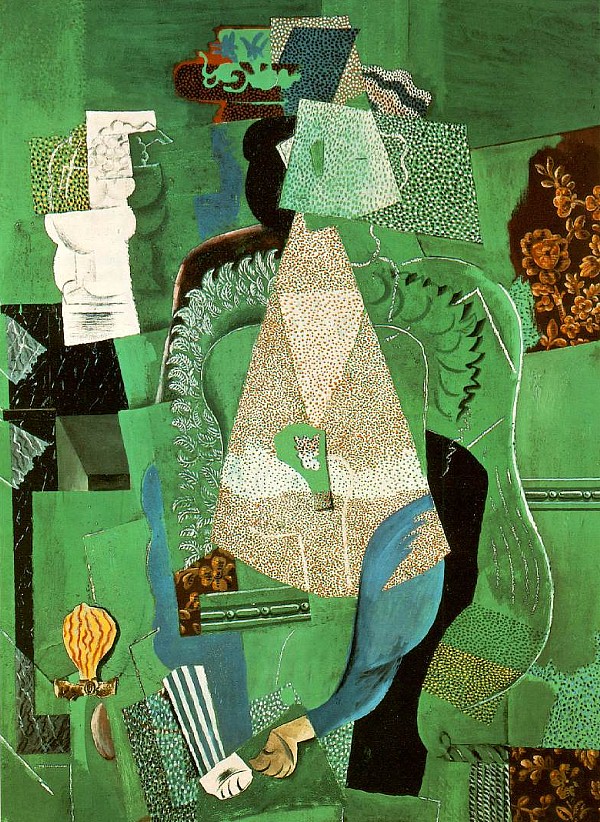

"Both Piranesi's Campo Marzio and Picasso's Dame au violon are "projects," though the former organizes an architectural dimension and the latter a human mode of behavior. Both use the technique of shock, even if Piranesi's etching adopts preformed historical material and Picasso's painting artificial material (just as later Duchamp, Hausmann and Schwitter were to do even more pointedly). Both discover the reality of a machine-universe: even if the eighteenth century urban project renders that universe as an abstraction and reacts to the discovery with terror, and the Picasso painting is conceived completely within this reality.

But more importantly, both Piranesi and Picasso, by means of the excess of truth acquired through their intensely critical formal elaborations, make "universal" a reality which could otherwise be considered completely particular."

Tafuri

beside the point and next to the point are the same thing [as tafuri said]?

|

www.quondam.com/e30/3016e.htm

|

Quondam © 2014.08.01

|

| |

2013.12.13 19:48

12 December

Also, I'm currently re-reading Tafuri's Architecture and Utopia, and I have a heightened awareness of the avant-garde architectural lineage that Tafuri sees the Ichnographia Campus Martius as the protogenitor of. I think it's now possible, however, to 'fabricate' a whole other avant-garde architectural lineage once one understands what the Ichnographia Campus Martius is really all about.

2013.12.23 19:47

23 December

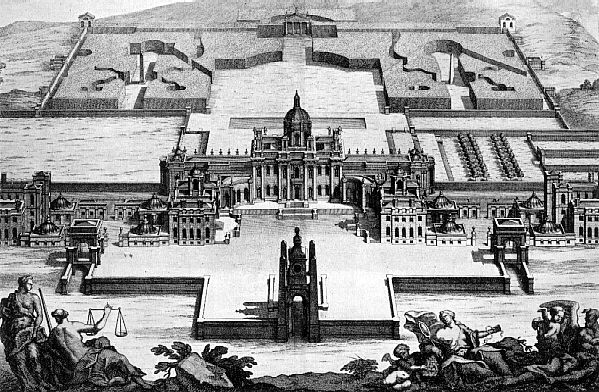

I'm now wondering whether the above image of Castle Howard from Vitruvius Britannicus (published 1715-1725) somehow inspired the architecture of Piranesi as delineated within Il Campo Marzio (1762). Remember the...

I was prompted by the "what is experimental architecture" thread to look again at "Piranesi's Campo Marzio: An Experimental Design." After reading a few pages it became evident that the essay/project could be 'rewritten' to deliver a whole other set of results, a whole other 'history.'

By covertly publishing the Ichnographia in a second state was Piranesi himself conducting an experiment to see who would ultimately discover the two different plans?

Piranesi's language of the plans relates back to the origins of Rom(ulus and Remus) itself.

"Both Piranesi's Campo Marzio and Picasso's Dame au violon are "projects," though the former organizes an architectural dimension and the latter a human mode of behavior. Both use the technique of shock, even if Piranesi's etching adopts preformed historical material and Picasso's painting artificial material (just as later Duchamp, Hausmann and Schwitter were to do even more pointedly). Both discover the reality of a machine-universe: even if the eighteenth century urban project renders that universe as an abstraction and reacts to the discovery with terror, and the Picasso painting is conceived completely within this reality.

But more importantly, both Piranesi and Picasso, by means of the excess of truth acquired through their intensely critical formal elaborations, make "universal" a reality which could otherwise be considered completely particular."

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development, p. 90.

There is no Picasso painting with the title Dame au violon, but it is possible that Tafuri is referring to Portrait of a Girl (1914):

Project: redraw the Ichnographia Campus Martius following the principles of Picasso's (Synthetic) Cubism.

2014.01.25 15:15

25 January

Finished reading Manfredo Tafuri: Choosing History this morning, and Leach is quite a good analyst and writer. I'd like to relate two passages, one from the beginning and one from the end. On page seven: "Beginning his studies in October 1953, Tafuri faced the disconcerting reality that the University [of Rome] remained stocked with professors appointed under the Fascist regime. Over the duration of his diploma studies, he came to openly oppose several of these. His "hit-list" included Enrico Del Debbio, Ballio Morpurgo, Vincenzo Fasolo and, most explicitly, Saverio Muratori. He complained of their lack of interest in teaching, their distance from the classroom and their reliance on assistants to deliver the curriculum. He begrudged their prejudice against modern architecture: "The operative principal was that contemporary architecture must not enter the curriculum. It was considered a heresy." It thus is now easy to speculate that Tafuri specifically set out to "modernize" Fasolo's analysis of Piranesi's Campo Marzio. If such is the case, then Tafuri also just continued Fasolo's mistakes. On pages 269-270: "In "The loneliness of the Project", Groys argues that the work practices of artists, philosophers, writers, scientists, and so on assume a fundamentally existentialist stance in the relation to their project to the external conditions of day to day life. He conceives of the project as intellectual work that is isolated and independent; its manifestations represent the project, but remain distinct from it. The very notion of the project, as Groys portrays it, invokes a fine balance between a common scale of time shared by all and a temporal field inhabited by an artist. In each instance that an artist proposes a project--to an ethical panel, funding committee, gallery, etc.--he or she advances a scheme for the future. To begin the project is to commence the realization of that programme. Anchored not to the vicissitudes of the present world, their vision is imbued with critique, hope of the anticipation of consequence. It is thus fundamentally utopian, an expression of the need to surpass the present: 'each project in fast represents a draft for a particular view of the future, and each case can be fascinating and instructive.' Despite the completeness with which the artist might conceive of this future, from the outside one may simple engage with its "evidence"." Choosing to "build" a virtual museum of architecture is definitely a project.

2014.02.18 19:01

18 February

Last night I read all of the 27 indexed citings of Kahn, L. within Tafuri's Theories and History of Architecture (1976), and [wouldn't it be neat when all texts are availble as ebooks you could then customize the order of the texts by order of index because] a somewhat revealing subtext manifest itself, like a strong, contiguous thread of thought came more and more into full focus. This will be further analyzed once all the passages are compiled and pieced 'chronologically' together.

This morning I read (again) a good bit of Biraghi's "Kahn as Destroyer" which begins with an analysis/interpretation of Tafuri's first published critique of Kahn's work--"Storicita di Louis Kahn" (1964)--which, from what I can gather, is a critique of Kahn's work via a review of Vincent Scully's Louis I. Kahn. One would hope that Tafuri could read English, but there was certainly nothing stopping him from scrutinizing all the numerous images that chronical Kahn's work up to that point along with some examples of historical context and/or inspiration. Thus, while looking at the images within Scully's Louis I. Kahn now, and at the same time being well aware of Tafuri's writings on Kahn, you can see what is the greater inspiration behind Tafuri's whole critique of contemporary architecture and 'history', even to the point where it was indeed Kahn that lead Tafuri to his 'analysis' of Piranesi's Campo Marzio. I'm still in the process of absorbing all this myself, but it turns out Kahn wasn't the 'destroyer', rather he was the inspiration to Tafuri's counterpoint. Basically, without Kahn the counterpoint would never have happened.

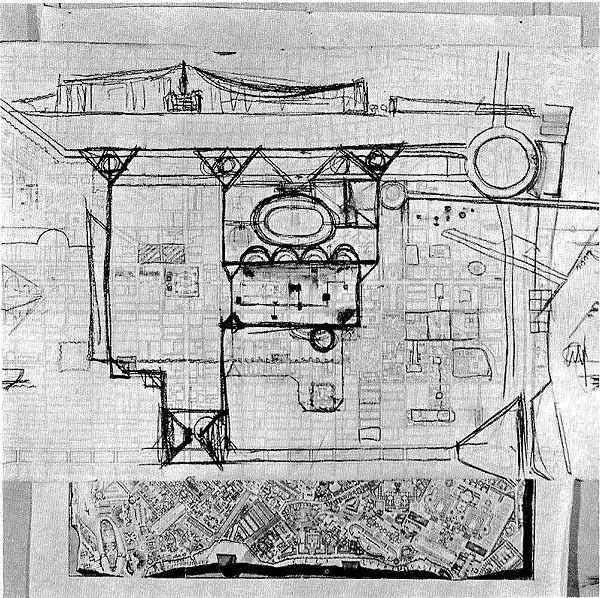

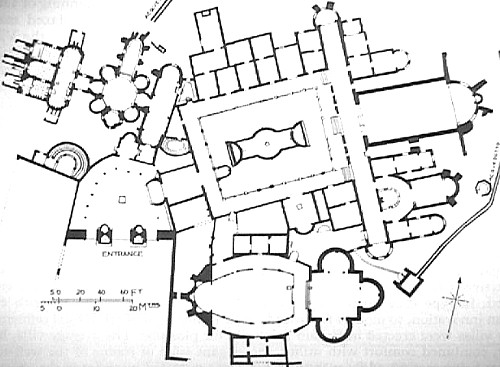

Two images of Piranesi's Campo Marzio appear within Scully's Louis I. Kahn: first the plan on its own, and second the plan with a Kahn sketch of Market Street East Redevelopment Project hanging over it.

"More directly, the shapes used by Kahn can be found not only in Choisy but also infinitely repeated in the composite photostat of Giovanni Battista Piranesi's map of Rome, drawn by him for his book on the Campus Martius, probably of 1762, which now hangs in front of Kahn's desk."

Vincent Scully, Jr., Louis I. Kahn (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1962). p. 37

Tafuri first presented the paper "Giovan Battista Piranesi. L'Architettura come 'utopia negativa' in 1970.

2014.02.21 18:32

21 February

The last mention of Louis Kahn within Tafuri's Theories and History of Architecture (1968) occurs on page 231, just six pages short of the textual end of the book:

"...let us try to re-state our initial proposition: criticism sets limitations to the ambiguity of architecture.

This means that the historian has to oppose the 'camouflaged anti-historicism' of present architecture. By writing past events into a field of meanings, the historian gives sense to the ambiguity of history: from abstract and completely available the ambiguity is rendered concrete and instrumentalizable. He will refuse to read in late-Antique architecture the premises of Kahn or Wright, in Mannerism those of Expressionism or of the present moment, in the pre-historical remains the premises of organicism and of some abstract experiences. And this refusal is a precise contestation of the mythologies of the pseudo-avant-garde."

As already cited earlier in the book, "late-Antique architecture" is short-hand for Hadrian's Villa and Piazza Armerina--"many late-Antique architectures from Villa Adriana to Piazza Armerina" (p. 110)--but it is also a veiled reference to Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius:

"The disarticulation of the spatial successions, in the Villa Adriana or in the Piazza Armerina, are so coherent with the premises that justify them--the test of the autonomy range of the single spatial fragment, modulated, contracted or made elastic, to emphasize its absoluteness and to increase its ambiguity within the entire context--as to make these works a sort of anthology, not only for successive studies, but also as sources to draw from: not by chance was a whole number of Perspecta taken up by the Villa Adriana [sic], and Kahn often showed his interest for this singular group of architectural objects.

What is of value in those exceptional late-antique monuments is the series of differentiated spaces that join and clash with one another: Piranesi's Campo Marzio, that owes so much to the study of the Villa Adriana, takes to the limit its formal bricolage, moving its search for a semantic polyvalency to another scale and to another historical context." (p. 113)

It's not clear why Tafuri considers Hadrian's Villa as an example of late antique architecture, since it was built almost two centuries before what is considered the late antique period. The Piazza Armerina is late antique, even possibly connected to Maximian and Eutropia, and it is quite possible that Tafuri uses the Paizza Armerina as an historiographical link between Hadrian's Villa and Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius.

So, in re-phrasing Tafuri's last mention of Kahn within Theories and History of Architecture we have:

"He [the historian] will refuse to read in [the] architecture [of Hadrian's Villa, the Piazza Armerina, and of Piranesi's Campo Marzio] the premises of Kahn or Wright..."

Tafuri's "refusal to read" is a direct rebuttal to a key passage within Vincent Scully's Louis I. Kahn (1962):

"Not so in the studies between the laboratories; their problem demanded a more complicated sequence of Form and Design, and its solution was again characteristic of Kahn. Early shapes used were pure derivations from the fanning pattern of the lower peristyle of Domitian's palace on the Palatine or from the "Teatro Marittimo" of Hadrian's Villa. It will be recalled that Wright had long before adapted the plan of the Villa as a whole for his Florida Southern College of 1939, and had used shapes from or related to it in later projects, while Le Corbusier had supplemented his sculptural Hellenic impulses with a series of drawings of the Villa's spaces which culminated in his top-lit megara at Ronchamp. More directly, the shapes used by Kahn can be found not only in Choisy but also infinitely repeated in the composite photostat of Giovanni Battista Piranesi's maps of Rome, drawn by him for his book on the Campus Martius, probably of 1762, which now hangs in front of Kahn's desk. Nervi, too, has used this curvilinear pattern in some of his ribbed slabs. Kahn had intended to support the studies on columns which arose from the associated garden at the lower level to grasp them about at the thirds of their arcs; but a further stage of Design intervened: the scientists could not see the sea from these shapes. Thus they were modified and the present simpler forms grew out of them.

Patterns from Rome and, most particularly, from Ancient Rome as imagined by Piranesi at the very beginning of the modern age, have played a part in the process at the Meeting House as well . An early sketch had been traced by a draftsman, partly as a joke, from a plan of one of the units of Hadrian's Villa itself. "That's it," said Kahn." (p. 37)

I never before imagined the prospect of considering Tafuri's Theories and History of Architecture a deliberate deterritorialization of the Philadelphia School.

2016.09.20 12:13

20 September

Whatever he was writing about--Rome in the 15th century, Venice in the 16th century, Piranesi in the 18th century--he was always looking for a battle. If there were two powers he was happy, because the notion of the dialectic was preserved. It was always the opposition between one and another, like Borromini and Bernini. When he was trying to write about an event, he tended to look not so much for a good guy or a bad guy, as for a red and a green, or a black and a white. In a way, then, Tafuri was interested in history because in it he could discover an opposition of characters, a clash of interests, or a war between social groups. It made, by the way, for very good writing. Up to a certain point, by shifting the attention onto this as against that, he could himself create the plot; that of a conflict in the Venice of the 16th century between families, parties, groups, interests. Today we are probably more aware of the meaninglessness of the chain of events, of the effect of chance on history, that time per se doesn't have any more meaning than the one we attribute to it. I often feel we are in this kind of chance-filled period nowadays…

Georges Teyssot, 1999

More directly, the shapes used by Kahn can be found not only in Choisy but also infinitely repeated in the composite photostat of Giovanni Battista Piranesi's map of Rome, drawn by him for his book on the Campus Martius, probably of 1762, which now hangs in front of Kahn's desk.

Vincent Scully, Jr., Louis I. Kahn (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1962). p. 37.

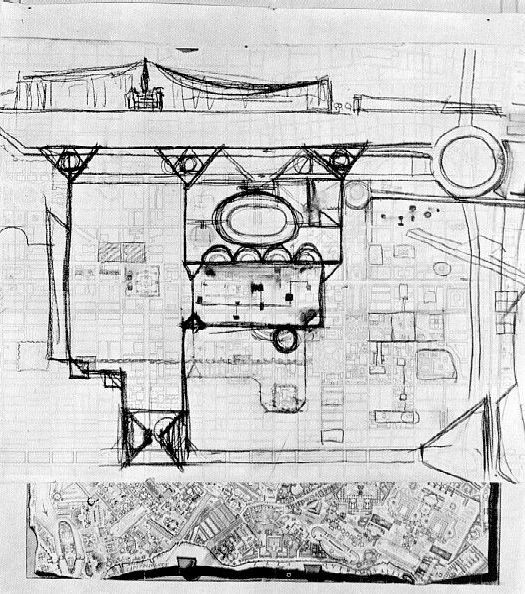

Viaduct architecture for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1962. Louis I. Kahn. Plan drawn over Piranesi's plan of the Campus Martius.

Did Kahn first see the Ichnographia Campus Martius within Hegemann/Peets' Civic Art?

Is it indeed the Ichnographia Campus Martius that is behind the change (of style/plan) from Kahn's 1956-57 Civic Forum to 1961-62 Market Street East?

|