2012.12.13 12:42

13 December

within the last twelve hours:

Writing Rome: Textual approaches to the city (again) . . . All Over the Map . . . "New Inquisitions on Architecture: From pluralism to narrative" . . . By leaving ideologies behind, architecture may fall into nihilism or else dissolve into a narrative dimension. Only through the mediation of a mythographic interpretation will the treatise and Utopia return to become part of the novel of architecture. . . . "Surrender: Ville Nouvelle Melun-Senart" . . . another, this time closer, look at Patent Office

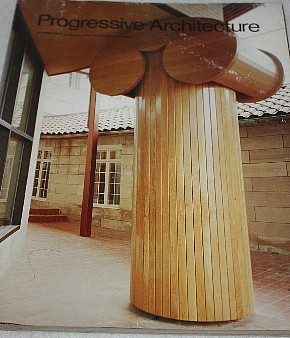

Found out this morning I successfully bid on this...

October 1977

| |

2013.01.26 18:29

Rem Koolhaas announces "Fundamentals" to be 2014's Venice Biennale theme

Perhaps underlying the theme is a wave of de-territorialization and re-territorialization that hasn't been registered yet.

I'd say a de-territorialized critic is even more dangerous.

2007.06.03

Not so much outside, rather, more beyond inside. Very much in the territory, but not within the normal restraints of the territory.

If you're in the fourth dimension, does that mean you can have your cake and eat it too?

2007.06.04

2013.01.25

Rem Koolhaas has stated: "Fundamentals will be a Biennale about architecture, not architects. After several Biennales dedicated to the celebration of the contemporary, Fundamentals will focus on histories – on the inevitable elements of all architecture used by any architect, anywhere, anytime (the door, the floor, the ceiling etc.) and on the evolution of national architectures in the last 100 years. In three complementary manifestations – taking place in the Central Pavilion, the Arsenale, and the National Pavilions – this retrospective will generate a fresh understanding of the richness of architecture's fundamental repertoire, apparently so exhausted today.

In 1914, it made sense to talk about a "Chinese" architecture, a "Swiss" architecture, an "Indian" architecture. One hundred years later, under the influence of wars, diverse political regimes, different states of development, national and international architectural movements, individual talents, friendships, random personal trajectories and technological developments, architectures that were once specific and local have become interchangeable and global. National identity has seemingly been sacrificed to modernity. ..."

And not Koolhaas:

2001.01.26

I'm trying to come to grips with the notion of why European colonials didn't simply accept the architectures that were indigenous to the lands that they (the Europeans) colonized. I see this as a negative action because I think a case can be made that many of this planets indigenous architectures are now virtually extinct because of Western colonialism/imperialism. During the first half of the 20th century, while large parts of the world were still colonies of Europe, Western modern architecture or the International Style (again a term used more for convenience) continued the global domination of Western style and furthered the extinction of indigenous architectures.

As much as I like Classical Greek and Roman architecture and Modern architecture, I nonetheless see it as a tremendous lose to architecture in general that these styles are now so global at what seems to be the expense of so many other architectures.

2003.09.01

...may indeed be right about there being a lack in architectural history when it comes to explaining shifts from style to style (and this interests me greatly), but I'm not convinced so far that evolutionary theory (which ever one that may be) is the best(?) way to explain shifts from style to style.

Up until (more or less) the "International Style", architectures where very much linked to geography/locale and the politics(/religion) that comes with geography. Of course, European colonialism can be seen as an "internationalization" (or is it "globalization"?) of European/Western architecture precursing the "International Style," as well as the beginning of the eradication of many indigenous architectural styles throughout the world. Is this history best explained as evolutionary? Is the shift from Mayan architecture to Baroque architecture in Mexico, for example, something evolutionary? Not exactly survival of the fittest; more like survival of the one's with the guns and the greed, and, oh yes, the holy mission to spread the Christian faith.

Personally, I sometimes wonder whether Mayan architecture may have sometime/somehow played an influencing/inspiring role in terms of (particularly) Spanish Renaissance and Baroque architecture.

2005.12.02

I agree that there is a kind of hegemony operating within architecture today (and definitely since the Modern Movement/International Style), but architecture wasn't always that way. Most of architectures' histories are like languages' histories in that they were all tied/related to specific places on the planet and reflected the culture of those places.

Reflecting on what presently constitutes architectural "history," perhaps architecture is now a world trade commodity more than anything else.

Is the next big thing to mix up the fashion brands? Wear your Foster pants with Woods belt over Eisenman panties?

Check out 1914.

And regarding architecture's "Fundamentals," compare and contrast Hamlin's Forms & Functions of 20th Century Architecture, volume 1 (1952). Chapters:

1. The Elements of Building: Introduction

2. The Use Elements of Building: Rooms for Public Use

3. The Use Elements of Building: Rooms for Private Use

4. The Use Elements of Building: Service Areas

5. The Use Elements of Building: Horizontal Circulation

6. The Use Elements of Building: Vertical Circulation

7. Mechanical Equipment

8. The Use Elements of Structure: Bearing Walls

9. The Use Elements of Structure: Non-Bearing Walls

10. The Use Elements of Structure: Doors and Doorways

11. The Use Elements of Structure: Windows

12. The Use Elements of Structure: Columns and Piers

13. The Use Elements of Structure: Beams, Girders, Ceilings, and Floors

14. Arches and Vaults I: Arches

15. Arches and Vaults II: Vaults

16. Roofs, Gutters, and Flashing

17. The Site in Relation to Building

18. Gardens and Buildings

19. Elements of the Modern Interior

20. Ornament

I'm interested to see if and/or how 'Ornament' will be present[ed] in 2014.

| |

2013.05.22 11:28

What are the cultural ingredients of architecture today?

$ is a perennial ingredient of architecture. Is China building so much because now they have lots of money? Yes. Does Dubai exist because of lots of money? Yes.

Just did a google search koolhaas yes culture.

"Junkspace pretends to unite, but it actually splinters. It creates communities not of shared interest or free association, but of identical statistics and unavoidable demographics, an opportunistic weave of vested interests. … Its financing is a deliberate haze, clouding opaque deals, dubious tax breaks, unusual incentives, exemptions, tenuous legalities, transferred air rights, joined properties, special zoning districts, public-private complicities. Funded by bonds, lottery, subsidy, charity, grant: an erratic flow of yen, euros, and dollars (¥€$)."

and

Let me ask you about your quote about the need to "accept the world in all it's sloppiness and somehow make that into a culture." Does this still reflect your current thinking?

Rem Koolhaas: Well, yes and no. Of course, behind every project we do there is a kind of vast critical apparatus of doing better. We're not trying to emulate the current mess. We are just as interested in the sublime. Actually, that is why I'm talking about the other buildings we are doing, because they are really exceptionally ambitious in terms of not emulating confusion or something, but ambitious as architectural works in and of themselves.

on architecture and capitalism . . .

Rem Koolhaas: I think what Mies tried to do is find a way to make the sublime compatible with capitalism . . . extract from capitalism the kind of elements that are sublime. . . . I think that the first real engagement with the aesthetics of capitalism is a kind of transcending it.

I think that after that, perhaps (Robert) Venturi and (Denise) Scott Brown were the second wave of looking at capitalism, perhaps with a greater sense of realism. The presence of capitalism and the results of capitalism were much more blatantly present, making it clear that you could almost not transcend it anymore, and you needed to find some accommodation with its aesthetics.

And I think that if you place Mies in the late 40's or early 50's, and if you place the beginning of the Venturi's thing in the late 60's or early 70's, then 20 years later of course globalization and the market euphoria become even more unfettered, and that is why I had to begin to look, with the Harvard project, at shopping, because I think that at that point almost all architectural production had contracted and focused on this one program, which in itself had morphed in such a way that it now included everything, all components. So for me, it was very important to address that, and also to see whether those demands had actually fundamentally changed the kind of spaces that we produce and the spaces that we need.

So you could say that the Venturi's are in the middle in terms of having a kind of positive relationship with the iconography of capitalism. Mies in a way stood above it, and Junkspace was a more internal look, when the positive attitude of the Venturi's was no longer tenable and where we had to admit and realize it was actually a much more ominous development. So, in a way, Junkspace is a theory, and what for me is very important about this building (the IIT Student Center) is that it tried to really work not so much within the same vocabulary but see what an architect could still do within that syndrome or within that regime.

You're so good at defining the reality of the world - the good things and the horrible things - that sometimes when I read your writings, it's very hard for me to see what you actually think about the things you're describing.

Rem Koolhaas: There are so many opinions in architecture. I think in the beginning it was just kind of exciting to describe and not to give so many opinions. If you read them (Koolhaas's writings), you also feel that you are in the presence of a very critical mind, or at least I hope so. Certainly in the case of Junkspace I think that should be overwhelming. But at the same time, I don't want to simplify things and say I'm against them when they have a degree of inevitability, but I would say our buildings are more and more able to really disconnect from those realities, or try to make the best out of them.

Is Bjarke "Yes is More" Ingels architecture's leading hipster?

Is "Design like you don't give a damn" implicit?

In perspective then: a monster[ous] grand tour[ism of] the real taboo domain.

Is Network Culture ever going to be a book?

"Look Bullwinkle, a message in a bottle!"

"Fan-mail from some flounder?"

Scripting. 3D printing. Ride the wave into the future?

"Architects inherently want to make the world a better place."

I attended a Denise Scott Brown lecture back in the (early-mid) 90s. She used the word 'boring" several times, as in, "Here's another boring plan." During the Q&A I wanted to ask, "So, are you trying to tell us that a bore is more?"

|