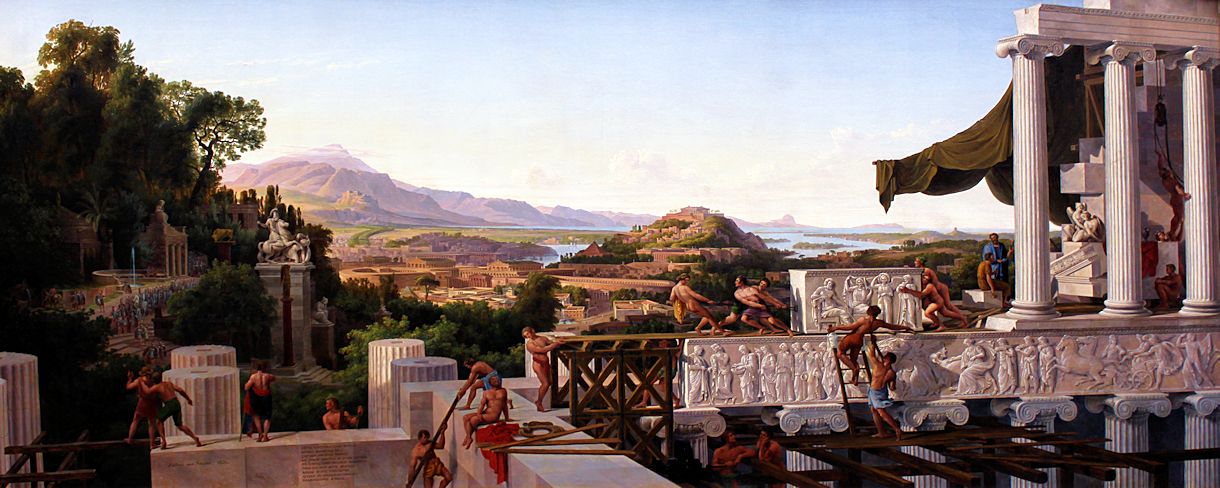

schinkel | Palace on the Acropolis Athens 1834 |

Just what in Schinkel's earlier career would have prepared him for a project of this scope and setting?12 While Schinkel's

architectural practice up to this moment had been limited to a northern European climate and topography, the classical villa--and more especially its Italian version--was already well known to him as an architectural prototype. During his Italian trips of 1803-1804 and 1824 he had examined it both in its ancient Roman form at Pompeii and as it had continued somewhat modified to his own day as a vernacular tradition throughout rural Italy and Sicily.13 The exquisite Charlottenhof in the park at Potsdam that Schinkel had remodelled for the Prussian crown prince in 1826-1827 was a Neoclassical maison de plaisance. The crown prince later proposed that Charlottenhof might be complemented by a spacious villa in the authentic antique manner. While making the plans, he attempted with Schinkel's help to reconstruct the two villas of Pliny the Younger--Laurentinum on the Sea and Tuscum--based on descriptions in Pliny's letters.14 Many had attempted to reconstruct these long-vanished villas for which Pliny had expressed such affection, beginning with the Venetian Scamozzi in 1615 in his L'Idea dell' architettura uniuersale15 In 1818, students at the French Academy had been invited to submit reconstructions of Pliny's Laurentinum as part of the Prix de Rome competition. The surviving entries observe a strict symmetry in keeping with the design principles of academic classicism. Schinkel's reconstructions from the difficult Latin text are freer and more picturesque in their asymmetry and have less of the abstractness of academic exercises. Here as on the Acropolis, Schinkel recognized that no authentic antique monument paralleled the rigidity of the modern academic approach, or as he put it in his earlier letter to Maximilian of Bavaria, "den lang abgenutzen neuitalienischen und neufranzosichen Maximen . . . worin besonders ein Missverstand in dem Begriff von Symmetrie soviel Heuchelei and Langeweile erzeugt hat und eine ertörende Herrschaft errange."16 By deviating from the prevailing criteria for classicism, Schinkel probably came closer to the spirit of the original.

|

|

|

|

www.quondam.com/54/5427d.htm | Quondam © 2017.01.13 |