hejduk |

|

| John Hejduk and the Cult of Humanism Kenneth Frampton |

|

|

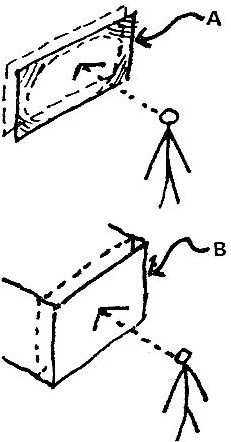

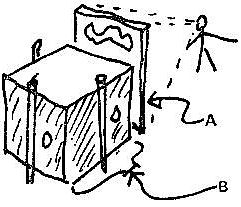

From the late 60's on, two basic motives informed Hejduk's formal invention--the one essentially external--the other internal. The first being the deliberate, perpendicular confrontation of the viewer/user with a shallow space field, into which he is implacably drawn by the primary object of his interest (i.e. the entrance to a house.) The second being the situation of the viewer/user within a fugal space sequence, where the identity of his particular situation at any moment is assured through variations in primary forms that

code the space like man-sized Froebel gifts.

|

|

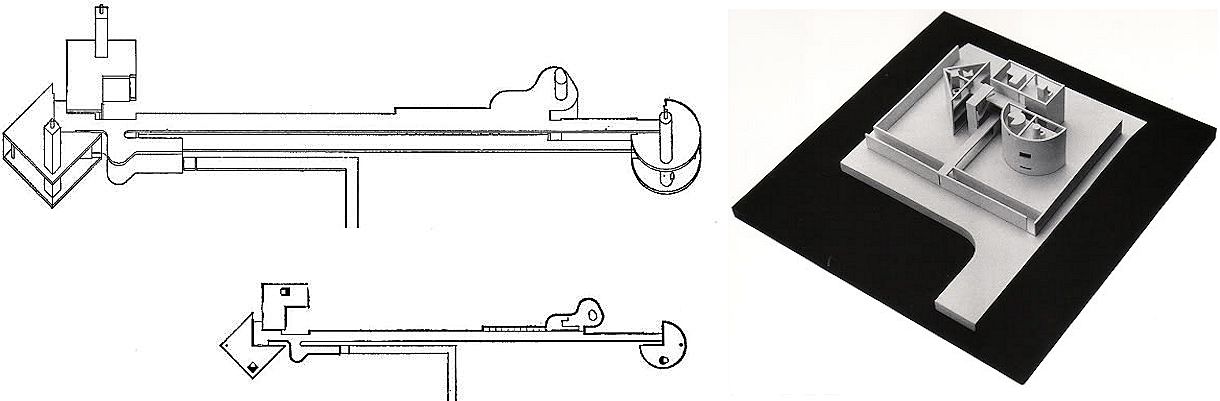

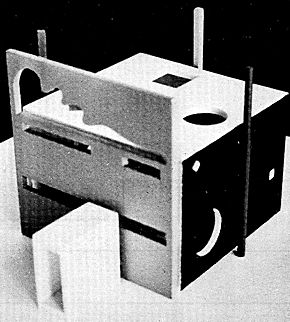

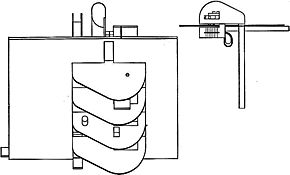

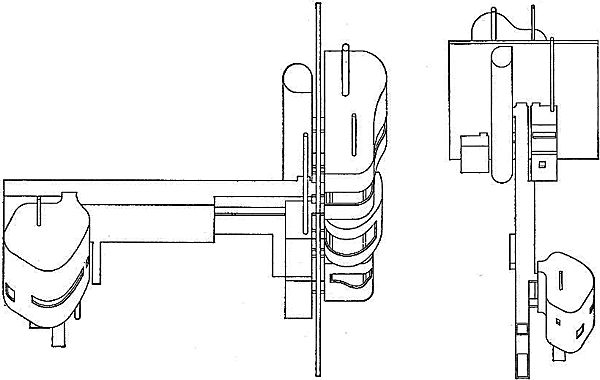

Two houses of 1966 exemplify the complementation and opposition of these basic motives. House No. 10 of that

year demonstrated the abrupt precipitation of the viewer into a 'shallow-space' field; a field that was first to be experienced as an inflection on the horizon and afterwards discovered as a narrow labyrinth comprised of three different terminal element; elements which were disposed about the ends of an attenuated 'picture-plane'. The contemporary One-Half House offered instead a clustered experience of

three very comparable elements within the confines of a walled patio. Where the one used 'three-quarter' elements (i.e. three-quarters of a square, a circle and a diamond respectively) situated at the extreme ends of an elevation, the other used 'half elements (i.e. half of a square, a circle and a diamond) in the center of an enclosed plan. Where the one was primarily an elevational idea that finally condensed

into a section, the other was largely a plan idea that was immediately experienced in terms of volume. Apart from these perceptual differences, the internal fugal space systems of these houses had much in common, each being 'coded' by free 'furniture'• elements, (e.g. chimney stacks) that reflected in their mass forms the volumes by which they were contained.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

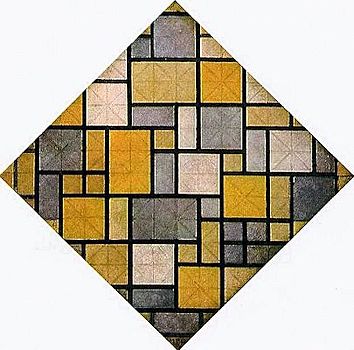

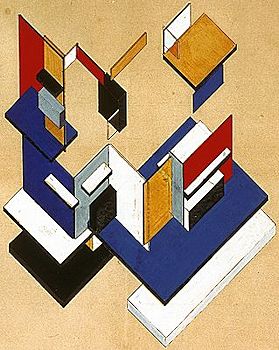

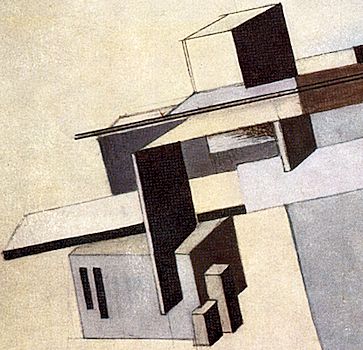

| Two interrelated questions arise at this point of impasse. The first concerns the respective limits of painting and architecture and questions the extent to which architecture may be legitimately derived from painting and vice versa. The second addresses the necessary interdependence of architecture and the city and challenges the urban relevance of Hejduk's work. The complex legacy of the Renaissance (always latent in architecture) is fatally linked to any answer we may attempt to these questions, as is the more modern and fragile tradition of Anti-Humanism, which outside of Cubism has been the essential contribution of Twentieth Century art. The achievements of Malevich, Lissitzky, Mondrian, Van Doesburg, Ozenfant and Le Corbusier come to mind not only for their intrinsic worth but also because each of these painters posited an architecture (some more elaborately than others) and the last, as the text of Vers Une Architecture makes clear, in terms that were entirely compatible with the traditions of Western Humanism. But the work of Malevich, Lissitzky and Van Doesburg was decidedly more complex since they projected an architecture that was as removed from classicism as it was from the vernacular. As Lissitzky's essay A and Pangeometry of 1923 makes clear, Suprematist-Elementarism posited an architecture that was the a-logical consequence of inverting the static pyramid of Renaissance perspective; while Van Doesburg in his Leonce Rosenberg projects of the same date, projected an architecture that was a direct exfoliation into three dimensions of the very essence of his abstract-planar painting. In first instance the generic four walls of architecture were obliterated through the illusory thrust of irrational perspective (c.f. Lissitzky's Prounraum), while in the second the most primal elements of architecture, such as a door or a window, were either eliminated wherever possible or systematically reduced. Both Suprematism and Neoplasticism thus posited a millennialistic anti-architecture in which an illusory painterly vision would invade and literally become the substance of the three dimensional world. On the other hand Le Corbusier's Purism, despite its dependence on distortion and free form, largely accepted the frontality of the Renaissance, however much its implicit perspectival pyramid had become flattened through the processes of Cubism. |

|

|

Piet Mondrian: Composition, 1919 |

|

|

|

|

www.quondam.com/57/5775k.htm | Quondam © 2020.11.17 |