8 August 1778

"I believe only him. I have no confidence in anyone but him."

8 August 1977

Fully packed for Rome. Luggage weighs 33 lbs. I weigh 172 lbs. Leaving for New York with $107.00.

8 August 1997

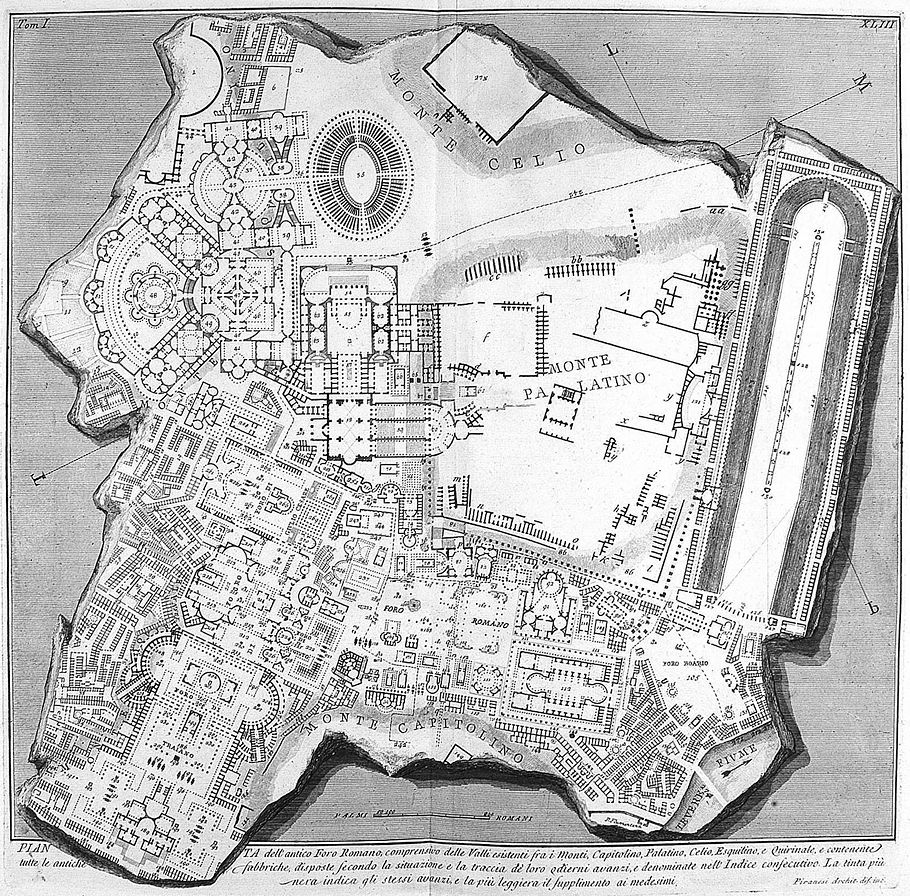

redrawing the Campo Marzio

After rereading some of Tafuri's text on the Campo Marzio, for some reason it dawned on me that my redrawing of the Campo Marzio is an attempt to walk in Piranesi's own footsteps, with the best of my ability, meaning, I am trying to learn how Piranesi's imagination operated by doing the same thing that he did--literally redrawing the plan. I am trying to get as close to Piranesi's own drawing/designing procedure.

I then thought of what Collingwood said about not being able to truly learn from history because we are not able to actually experience history. In this sense I am trying to re-experience a specific historic occurrance, albeit over 200 years later and with a radically different drawing technology. Besides the use of CAD, which is actually related to engraving in that it is a type of "drawing" that is readily reproducible, the major difference between what Piranesi did and what I am doing is that Piranesi was designing the plan(s) as he was drawing them, he was producing with his imagination and with his graphic dexterity. Whereas I am only measuring his work and then digitally inputting the data. I am learning through osmosis, however.

This here is the beginning of my personal story/essay about my own redrawing experience. Besides my initial incentive for starting the project in the first place, (which I believe I have some notes on already). I will also relate the stages along the way. I will demonstrate the process by actually recalling the order in which the drawing was produced (and the times I did the drawing, as well). For example, I can tell the story about how I discovered the long axis because of the pervasive orthogonality of the Bustum Hadriani sector. This is only one of the examples of where I learned something because of and during the redrawing process--there are many more and I will have to document them by going through my notes and time sheets, and start a timeline web page.

The title of my essay (which I just thought of) is "Redrawing History: G.B.Piranesi's Campo Marzio in the Present," and, in fact, the whole book project may take on that name. This is another breakthrough for me because I am witnessing this whole Campo Marzio project coming together in ways that I didn't even expect. I will just keep plugging right along, and I now have even more reason to read about the philosophy of history. So as not to forget, I also have the opportunity to delve into the virtual realm and how reality and the virtual very much cross paths in the Campo Marzio.

8 August 2022

I was going to start the day writing 'a footnote and Paulette Singley,' an email regarding Mario Bevilacqua, Heather Hyde Minor, Davide Tommaso Ferrando, Cynthia Davidson, Andrew Kovacs, Orhan AyyŁce, Chris Teeter, and Paulette Singley being invited as voluntary, albeit autonomous co-authors of "The Discovery of Piranesi's Final Project." The email was never written, but the notion of co-authorship remains viable. Instead, I collected textual passages pertaining to Piranesi's longtime bladder ailment which may well have precipitated his ultimate demise:

Late in 1777 or in the spring of the following year, he set off for Naples, accompanied by Francesco, by his veteran assistance Benedetto Mori, and by August Rosa, an unsuccessful architect who made a precarious living from the sale of cork models of antiquities. It was a tiring journey that would have taken three or four days and when they arrived he turned down Francesco's suggestion that he ought to take a rest; they pressed on south to Paestum, and immediately set to work sketching the ruins.

Jonathan Scott, Piranesi (1975), p. 251.

He [Piranesi] returned to Rome a dying man, but he insisted on continuing with his etching. When a doctor was suggested, he called for his volumes of Livy: "I have no confidence in anyone but him." Towards the end, despite acute pain, he refused to stay in bed. "Rest is unworthy of a citizen of Rome; let me see my models again, my drawings, my plans," He died on 9th November 1778 and was buried not, as he had intended, in the church of S. Maria degli Angeli in the Baths of Diocletian, but in his parish church of S. Andrea delle Fratte. A couple of years later, at the request of Cardinal Rezzonico, his remains were moved to his own church on the Aventine.

Jonathan Scott, Piranesi (1975), pp. 253-4.

...the temples at Paestum... Although the evidence is meagre it would appear that Piranesi accompanied by Francesco and their architectural assistant, Benedetto Mori, made an expedition in 1777-78 to examine these Greek temples situated a few miles south of Naples. The father was already suffering from a severe bladder complaint which ultimately caused his death in Rome during the November of 1778.

John Wilton-Ely, The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1978), p. 117.

Piranesi died on 9 November 1778 after heroic resistance to a particularly painful illness aggravated by his dedicated activities.

John Wilton-Ely, The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1978), p. 119.

On All Saint's Day, one of the greatest artists of the eighteenth century lay dying. Few Romans would have noticed. Nearly everyone was attending to their own dead, gathering sweet almond biscuits and candies to take to the city's cemeteries to celebrate the feast of All Souls the following morning. For eight days the bladder ailment that had tormented him for more than a decade intensified its assault on Giovanni Battista Piranesi. He believed that his family was trying to poison him, insisting in the days before his death that one of his workshop assistants bring him his food to prevent his family's access to his plate. His son suggested a doctor. Piranesi refused, pointing to his copy of Livy's history of Rome and saying, "I believe only him." But belief was not a cure. On November 9, 1778, Piranesi died. Learning of his death, an old Venetian friend wrote, "I heard rumors here [Venice?] that before he died he hid his money (which must have been abundant) so well that his children despair of finding it. Indeed, it is said that he died crazy. If the strange things that people are saying are true, it cannot be otherwise."

Heather Hyde Minor, Piranesi's Lost Words (2015), p. 1.

|