2012.07.10 20:52

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

In an October 1969 ("The Big Little Magazine: Perspecta 12 and the future of the architectural past," Architectural Forum) review of Perspecta 12, Peter Eisenman writes:

"It is difficult to judge in retrospect whether Perspecta, while purporting to be a reflection of history, was not in itself creating history. And while the making of history cannot, of course, be directly ascribed to Perspecta, one can practically trace the history of post-war American architecture through its pages, from the appearance of Paul Rudolph's early Florida houses in Perspecta 1, to the Adler and DeVore houses of Louis Kahn in Perspecta 3, which in a quiet way signaled a significant, if marginal, change in the course of the Modern Movement--the eclipse of the free plan and a return to a direct modulation of space through structure."

| |

Eisenman continues:

"There has unfortunately flourished, since the war, around the Modern Movement, a body of secondary literature which has tended not only to obscure some of the original ideas adherent to this movement, but also in some cases, in a search for an over-simplified version of history (and because of highly simplistic criteria of explanation), created an idealized picture of it--which can hardly be regarded as a representation of reality. Thus, Kenneth Frampton's article on Pierre Chareau's Maison de Verre, both in its style of presentation and its choice of material, can be seen as a break from this tradition. And while such a documentation of this building, as well as other canonical works of the Modern Movement, is long overdue as a contribution to the history of the recent past, it is the quality and scope of the documentation which commands our attention. Here is a set of precise, hard-line drawings, restrained, elegant, almost in the genre of the building itself, which certainly must establish a standard for such a presentation. But further, it is the abstract style of drawing in itself, the emphasis on plan, section, and axonometric view, which makes them useful for an analytical approach to the building. It is important to note that it was Frampton who had these drawings made in this particular manner; first because they probably did not exist, and second, because they present the building and the ideas inherent in it in a way that is not possible to retain, even when one is confronted with the actual fact."

| |

Thirty-five years later Eisenman publishes Ten Canonical Buildings 1950-2000 (2008), where Louis I. Kahn's Adler and DeVore Houses are featured (which actually makes for a total of eleven canonical buildings within the book, but who's counting). Regarding the Adler and DeVore Houses:

"In the Adler and DeVore Houses of 1954-55, unlike in many of his other projects, Kahn achieves what could be considered an architectural text in diachronic space. This is brought about by the superposition of classical and modern space; that neither of these "times" dominates results in a dislocation of moments or, in other terms, a disjunction that is experienced in space. In the Adler and DeVore Houses, Kahn presents architecture both as a complex object and as the potential for the subject to experience the object as both a real space and an imaginary space. Both conditions are present and can be read, each in turn displacing the other. It is this unresolved moment in the Adler and DeVore Houses, which are themselves suspended in real time between the Trenton Bathhouse and the Richards Medical Center, that makes these two houses different from much of Kahn's other work. It is in the context of the denial of axial symmetries and part-to-whole relationships evident in much of Kahn's later work that these differences lie.

Thus the Adler and DeVore Houses can be seen to articulate an alternate internal logic: first, as a conscious, didactic proposal against the free plan of modern architecture, and second, as a critique of modern architecture."

To be precise, the Adler and DeVore Houses (1954-55) predate the Trenton Jewish Community Center Bathhouse (1956-57).

| |

Eisenman continues:

"The hipped roofs of Kahn's Trenton Bathhouse, as well as its emphatic materiality, are clearly antecedents to the Adler and DeVore Houses, given that initial sketches of both houses similarly have hipped roofs. The Trenton Bathhouse is the first example in America of a massive brick and concrete structure denying the free plan and dynamic asymmetries of modernism with a classicizing nine-square plan. While only a small portion of the Trenton Bathhouse was built..."

Again, it is in fact the early hipped roofs schemes of the Adler and DeVore Houses that are antecedents to the Trenton Bathhouse, and, as built, the Trenton Bathhouse is complete. Eisenman confuses the Trenton Jewish Community Center Bathhouse with the much larger Trenton Jewish Community Center Community Building which was a wholly separate building design never executed.

| |

When seen in (correct) chronological order and at the same scale, a number of Kahn designs, centering on the Adler and DeVore Houses, reveal a more interesting evolutionary development of the "eclipse of the free plan and a return to a direct modulation of space through structure."

Fruchter House 1952-53

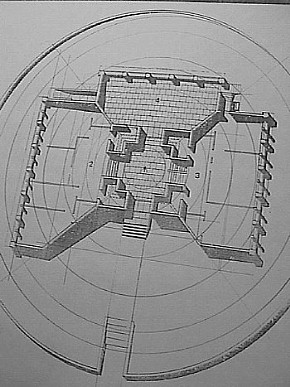

Adler House 1954-55

DeVore House 1954-55

Trenton Jewish Community Center Bathhouse 1956-57

Trenton Jewish Community Center Day Care 1957

Goldenberg House 1959

Fisher House 1960-67

Also see the Patzau House and the White House.

|