LeDeuzzy, Q. |

I believe in multiple choice |

|

|

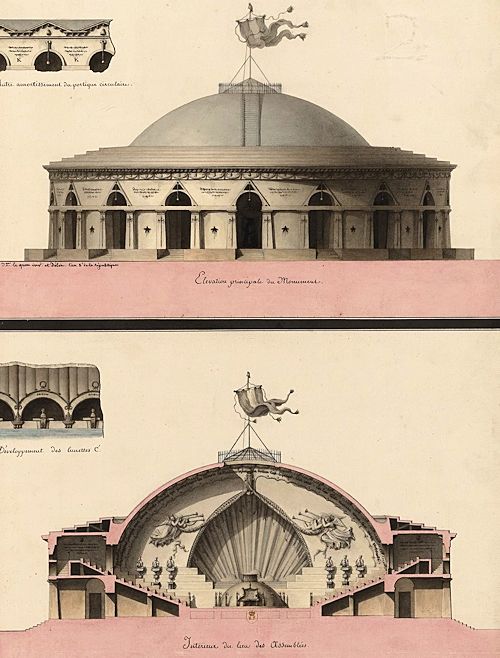

In the year IX Lequeu entered the competition for the erection of commemorative columns in the départements, and in the year XI he took part in another held in the Galérie d'Apollon in the Louvre.

|

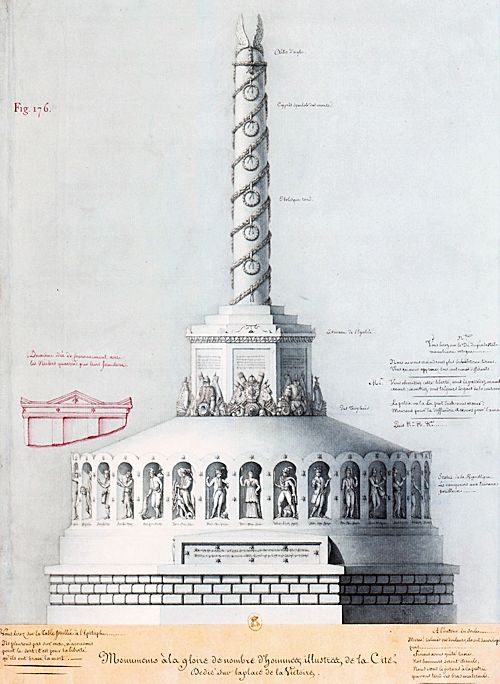

The latter was pleased with the extravagant composition and the drawing went on exhibition in the Salle de la liberte. Later, Lequeu wrote on the back of this life-saving drawing the remark, "Dessin pour me sauver de la guillotine" and the ironical comment, "Tout pour la patrie." In the same year II and the same place he exhibited also the project of the in Honor of Illustrious Men, to which he had added the timely verses: "Ne pleurons pas sur eux, n'accusons point Ie sort; C'est pour la liberté qu'ils ont bravé la mort." | However, the strictly antiRevolutionary gloss on this drawing most certainly was written when there was no more risk in siding with the conservatives. It refers to the victims of the Terror, "Ce temps où on immolait des victimes humaines à la liberté." The patriotic plan of the year I, "Monument destiné à l'exercice de la Souveraineté du peuple" may just as well have been inspired by enthusiasm as by fear. |

I believe that not a personal condition, but the general unrest of the period must account for his production in the first place. Lequeu's dream-architecture marks the end of the period at the beginning of which stand the architectural dreams of Le Geay. Though Lequeu wandered beyond the regular bounds, his fantasies are more than extravaganzas. They are works of art in which we recognize the man, and through which we apprehend the period. Building for patrons after classical canons must have been for Lequeu in his early years just as boring as delineating charts and maps in his advanced age. Classicism was the field in which the unoriginal, the minor spirits, felt at home. The independent minds strove to free themselves from the old heritage, in one way or another. They laid down their novel ideas in passionate words, or in ecstatic designs which must be looked upon as expressions of evolution. To measure their inventions by the standards of a perfected, stable style or tradition would be to misjudge their position and significance in the history of art. They are neither to be judged by any aesthetic canons of mature style, nor to be approached with any expectation of practical utility or even possibility. If ever there was such a thing as l'art pour l'art, we find it in the outbursts of the revolutionary architects. Unlike the artists at the end of the nineteenth century, they were not out to discover some novel art. They were less artificial than those who belonged to the art nouveau movement. Boullee, Ledoux, and Lequeu had to speak out because they were swayed by the emotions and the needs of the moment. The transition from a stabilized tradition to diametrically opposed goals brought about an uproar in any field. Contrary to other historians, art historians were not aware of the crisis of the close at the eighteenth century. They registered . . . . . . see the seers. Like the heroic architecture of Boullée and the reform work of Ledoux, Lequeu's fantasies reflect the main trends of the period, its passion for grandeur, its will to innovation, and its yearning for the unheard-of.

|

|

|

|

Lequeu's Work

|

Baroque and Classicism

| Not much later the pompous, overdecorated chapel of Sainte-Genèvieve in the Emperor's Palace must have originated. Lequeu noted on the back that it was shown to Soufflot and the King. |

3201i

| Quondam © 2020.01.01 |