LeDeuzzy, Q. |

I believe in multiple choice |

|

|

|

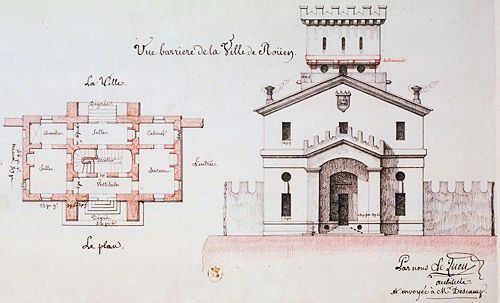

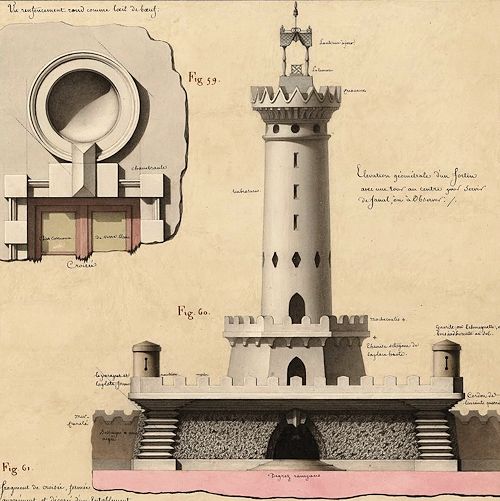

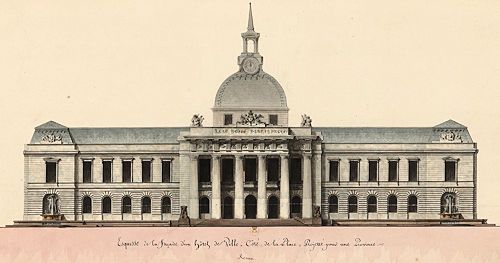

Quite different is the design of a barrière for Rouen. An inscription on it states that it was sent to Descamps, "Par nous Le Queu architecte et envoyée à M. Descamps." From this self-confident, almost childish enunciation, and from the immature character of the drawing itself, we may infer that it was made when Lequeu was a student under Descamps, or even at an earlier moment when he wanted to show his hand to the master. The barrière in the "castellated" style is a product of early Romanticism. The porch of the plain house is . . . mented tower rises above the roof. | The Small Fort (Fortin) is likewise derived from medieval castles. The plasticity of its rendering points to a later date. | In 1779 Lequeu made a design for a Town Hall. He evidently hoped that his project might be accepted to replace the scheme which Antoine Mathurin Le Carpentier, a member of the Paris Academy of Architecture,had worked out for Rouen in 1758. According to Lequeu's own statement the Royal Academy of Rouen approved of his design which belongs to the type of cool, impersonal . . . The elongated structure consists of a rusticated groundfloor with arched windows and a second story with straight-headed openings. The central Doric portico runs up to the height of the Mansard roof; slightly projecting end-pavilions frame the whole; a dome with a spire terminates the composition. The arrangement is, basically, Baroque, but all Baroque liveliness has gone. There is no movement in the front, and the single elements appear to be frozen. Lequeu's project differs from Le Carpentier's chiefly in two ways. It lacks the latter's rich decoration, especially the columns of the second story; and the central portion is considerably altered. The old-timer Le Carpentier was still intent upon unification. To this end he used the two-story pattern both in the center and on the sides. Lequeu, however, disrupts the continuity of the front by adding the colossal portico. His dome is less conspicuous than that of the former master, who exalted the crowning feature . . . . . . main floor of the building. Though Lequeu's design is based on that of his predecessor it reveals unmistakably a changed attitude toward composition. |

|

|

|

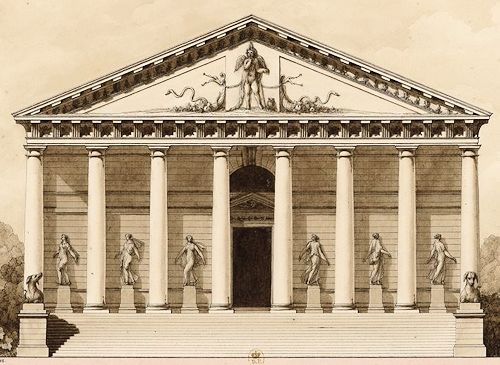

In the Casino of Terlinden at Sgrawensel, built for a certain dowager Meulenaer in 1786, the main entrance is on the short side of the rectangular plan, like . . . . . . ancient temple. But the porch is followed by the staircase, behind which the rooms are lined up in two rows. The plan is definitely lacking in centralization, or orientation around a dominating element, and this is contrary to truly Baroque plans. A structure that was supposed to imitate a classical temple did not, of course, permit a centralized arrangement. The architect was not free in designing the plan. Yet it is significant that the patron himself followed the new fashion. In the era of the Baroque the formal pattern was imperative and no patron would have wanted a house deviating from it. Whoever was responsible for the temple-dwelling of Terlinden, its interior indicates that the loose arrangement of the rooms was satisfactory at that moment. The interior decoration was strictly Louis Seize, stiff and rather closely following Greek models. A Memorial in the garden, erected to enshrine the bust of a woman, foreshadows Lequeu's later inventions. It shows various odd details, such as the upright wreath on top of the framing arch, and the bird-wings affixed to its sides.

|

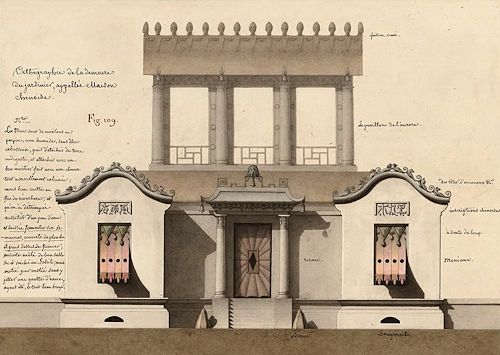

Exoticism

| a Chinese House, |

www.quondam.com/90/9002c.htm | Quondam © 2020.01.02 |