discovery

1999.05.14

...discovery of the two states of the Ichnographia today at the Fine Arts Library of the University of Pennsylvania.

overall, one very Piranesian daze

2000.04.05

4 April 2000... ...successfully documented the two states of the Campo Marzio.

overall, one very Piranesian daze

2000.04.06

...the first documentation of the heretofore undetected two differing published states of Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius, the six fold-out plates that comprise a reenactment plan of ancient Rome within Piranesi's larger Il Campo Marzio dell'antica Roma 'archaeological' publication. After many years of redrawing and analyzing a printed reproduction of the Ichnographia, I went, on May 14, 1999, to see an original version of the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania's Fine Arts Library. Within minutes of having a 'real' Ichnographia unfolded in front of me, I noticed that the Circus of Caligula and Nero is not only labeled, but also configured somewhat differently than the circus plan I was used to seeing. Of course, I was instantly very excited because nowhere have I ever read about the Ichnographia having two editions/states (like Piranesi's Carceri/Prisons have two published states/editions), and these two different plans are definitely not noted within Wilton-Ely's recent Giovanni Battista Piranesi - The Complete Etchings. Moreover, I believe I discovered something that no other architect, architectural historian, or art historian had noticed before. I then quickly scanned the rest of the plan to see if any other differences existed, and, sure enough, the Circus Agonalis is likewise different than the plan commonly reproduced. On 4 April 2000, I finally returned to Penn's Fine Arts Library to document the two different Ichnographia via tracings and taking digital images:

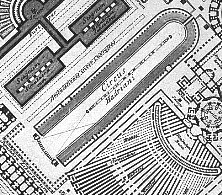

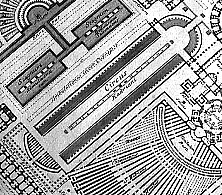

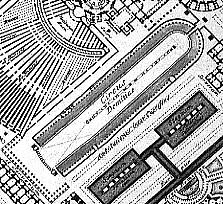

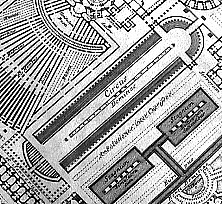

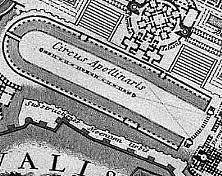

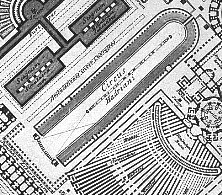

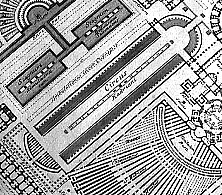

The image above left is the Circus of Caligula and Nero as the Ichnographia is commonly reproduced. The image above right is the Circus of Caligula and Nero as it appears within the University of Pennsylvania's (original) copy of the Campo Marzio.

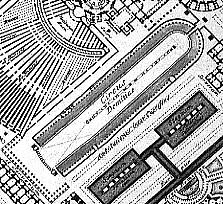

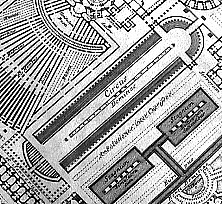

The image above left is the Circus Agonalia as the Ichnographia is commonly reproduced. The image above right is the Circus Agonalia as it appears within the University of Pennsylvania's (original) copy of the Campo Marzio.

The differing plans raise several questions:

Did Piranesi himself make these changes, or did perhaps his son Francesco, and if Piranesi made them, then why?

Which set of plans were 'drawn' first?

Does this 'change of plan' carry any possible semiotic or symbolic message regarding the Ichnographia's larger meaning?

Does this physical evidence offer any indication of Piranesi's 'design' method?

| |

one more Piranesian daze: circus act

2000.05.15

In attempting to discern the possible reason or message manifested by the plan changes to the Circus of Caligula and Nero and to the Circus Agonalia, I began to think of these specific circuses and how they may or may not relate to the numerous other circuses delineated throughout the Ichnographia. Within the version of the Ichnographia that is presently widely published there are six circuses, the Circus Caji et Neronis, the Circus Agonalia, the Circus Hadriani, the Circus Domtiae, the Circus Flaminius, and the Circus Apollinaris. With only minor adjustments to length, each circus is delineated in a virtually identical fashion, and, moreover, each circus reflects an archaeologically correct circus plan. As already illustrated, the plans of the Circus Caji et Neronis and the Circus Agonalia within the University of Pennsylvania Ichnographia reflect more stylized, i.e., archaeologically incorrect, circus formations. Since all the circuses are identical in the widely published version of the Ichnographia, I then began to wonder, via transposition, whether all the circuses within the Penn Ichnographia were likewise identical there in the form of exhibiting plan changes. In all honestly, I had not noticed any plan changes to the circuses other than the Circus Caji et Neronis and the Circus Agonalia the two times I had seen the Penn Ichnographia prior, but nor did I have any pictorial hardcopy evidence that there are no other plan changes. Having worked with the Ichnographia for over ten years, if I have learned anything, it is that the Ichnographia, no matter how well you think you know it, continually maintains the uncanny ability to beguile. Therefore, it was necessary for me to once more return to the other Ichnographia.

Upon doing further research, i.e., going back to the University of Pennsylvania's Fine Arts Library to again scan the Ichnographia Campus Martius, more plan changes were indeed discovered, and, just as I had begun to suspect, the "change of plans" effected the Circus Hadriani, the Circus Domitiae, the Circus Flaminius, and the Circus Apollinaris. Thus, it is now evident that each of the major "changes of plan", between the Ichnographia Campus Martius that is widely published and the Ichnographia Campus Martius within the rare book collection at the University of Pennsylvania's Fine Arts Library, occur more or less exclusively within those buildings of the Ichnographia labeled "circus".

The plan above left is the Circus Hadriani as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Hardiani as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

The plan above left is the Circus Domitiae as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Domitiae as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

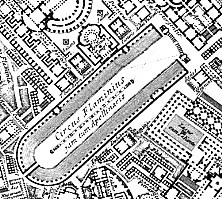

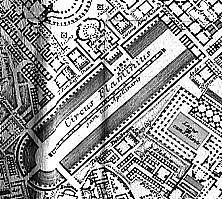

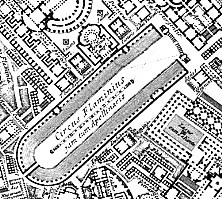

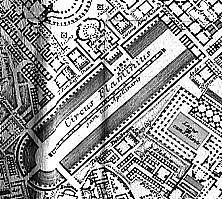

The plan above left is the Circus Flaminius as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Flaminius as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

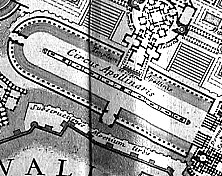

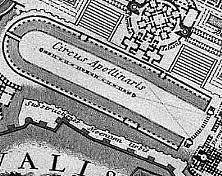

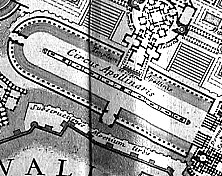

The plan above left is the Circus Apollinaris as it appears within the commonly reproduced Ichnographia. Above right is the Circus Apollinaris as it appears within the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania.

As the above plan comparisons indicate, the newly discovered circus plans engage directly with their neighboring buildings, thereby rendering a connected contextualism and demonstrating a more integrated urban planning methodology. The circus plans of the commonly reproduced Ichnographia on the other hand, albeit archaeologically correct, do not engage their immediate surroundings, and appear as though literally afterthoughts. Beside the already mentioned questions as to what these changes might mean and which set of plans came first, or what Piranesi's intentions in making the changes might have been, there is now an additional question as to why the changes were specifically and only applied to the Campo Marzio's six circuses.

|