Vincenzo Fasolo, "The Campo Marzio of G. B. Piranesi".

2691b

1956

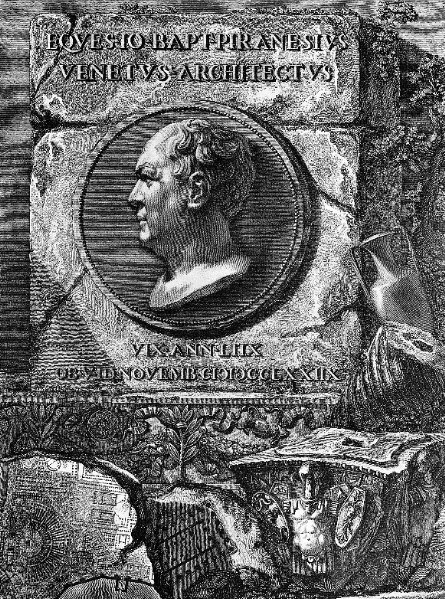

the portrait of Piranesi

1998.06.28

There is a portrait of Piranesi engraved by his son Francesco. The portrait is a profile set in a medalion, and the overall composition of the plate is in the Piranesi style. In the lower left corner, there is a stone fragment carved with plans, and it is indeed a fragment of the Ichnographia, specifically the Theater of Marcellus, the Minutia Vetus, and the Porticus Octavae. ...wonder if Francesco, or even Piranesi himself, saw the Ichnographia as Piranesi's greatest achievement. The four-sided Temple of Janus is also clearly delineated on the fragment.

...a case for the father-son theme that begins with Mars and Romulus (inversely God, the Father and His Son Jesus), and could include Augustus and Agrippa, and Trajan and Hadrian, and even Theodosius and Honorius.

Piranesi lives in the "Garden of Satire"

1998.07.07

...since Piranesi came to live at the top of the Spanish Steps, he may then have placed the Horti Luciliani purposefully in the same location within the Ichnographia. If this is so, then Piranesi deliberately places himself (figuratively) within the garden of the father of Roman satire. ...find the exact location of Piranesi's home, check its locationon the Nolli map, and then find the exact location within the Ichnographia. ...not sure if the exact spot will be significant, but it will be good to know nonetheless.

Piranesi lives in the "Garden of Satire" 2

1998.07.07

...I'm not absolutely certain that this is where Piranesi lived in 1757. ...could this be seen as Piranesi directly identifying himself with Lucilian as a "modern" father of Roman satire.

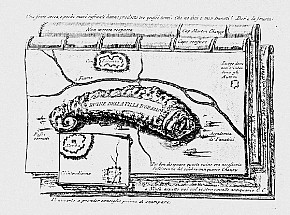

...find out if Piranesi has in other cases made a direct connection between himself, his work and satire. There is one engraving called Satirical vignette against Bertrand Chaupy something where an island(?) is made to look like a turd.

| |

reading about Piranesi in Scott

1998.07.29

...Piranesi moved to the top of the Spanish Steps [hence, within the "Garden of Satire"] the year the Campo Marzio was published (beginning of chapter VII, p. 163).

Piranesi: inter-disciplinarian

1998.12.20

...Piranesi employing both archeological skills and architectural/urban design skills to engrave the Ichnographia.

Encyclopedia Ichnographica

1999.11.07 20:43

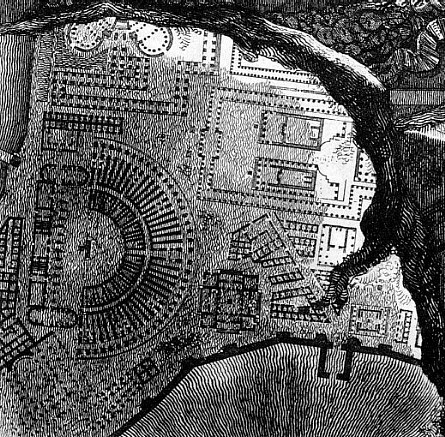

As it stands now, my ongoing investigation and redrawing of the Ichnographia has led to the 'discovery' of a whole new aspect of Piranesi's work that so far no one else has found, namely that the large plan of the Campo Marzio is a readable narrative of Ancient Rome's political and architectural history--but in order to grasp this delineated 'text' one must 'read' in unison the individual plans, the plans in relationship to each other, the plans in relation to where the actual buildings really were, and (this is perhaps the most important) the Latin labels Piranesi gives to each plan.

The City of Collective Memory

2000.03.30

Piranesi also borrowed the devices of Baroque scenographers, heightening the impact of his fantastical compositions of Rome by twisting and turning their viewpoints, creating a confused montage of fragments and spaces, of exaggerated proportions and depth. If Greek architecture was the epitome of purity and restraint, then Roman architecture, so Piranesi surmised, had been erected by plunderers and despoilers, and its compositional forms were not only eroded by time but compromised by choice. Roman ruins were exceptions to the ideals of purity, existing beyond any order that classicists might impose. Their mysterious allure resided instead within irrational and archaic realms. So Piranesi, a bricoleur in search of new orders and new inventions, turned away from those who poked around for the origins of architecture among its ornaments and stones and reached beyond the contemporary zeal for restoration. He moved instead into an arbitrary, utopian, and entirely imaginary sphere of subjective experience. Fantasy holds an essential role in any "analogous city" view, for fantasy is the mediator between an archeologist's mind bent on exploring roots and remnants of antiquity and a creative imagination that quotes and remembers only arbitrary and unrelated fragments and traces. Through incongruous recombinations and imaginary superimpositions, Piranesi diverted architectural symbols from their original meaning. He played an enigmatic game of architectural writing in which reality and the imaginary are confused.

M. Christian Boyer, The City of Collective Memory : its historical imagry and architectural entertainments (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1994), pp. 176-8.

overall, one very Piranesian daze

2000.04.06

...the first documentation of the heretofore undetected two differing published states of Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius, the six fold-out plates that comprise a reenactment plan of ancient Rome within Piranesi's larger Il Campo Marzio dell'antica Roma 'archaeological' publication. After many years of redrawing and analyzing a printed reproduction of the Ichnographia, I went, on May 14, 1999, to see an original version of the Ichnographia at the University of Pennsylvania's Fine Arts Library. Within minutes of having a 'real' Ichnographia unfolded in front of me, I noticed that the Circus of Caligula and Nero is not only labeled, but also configured somewhat differently than the circus plan I was used to seeing. Of course, I was instantly very excited because nowhere have I ever read about the Ichnographia having two editions/states (like Piranesi's Carceri/Prisons have two published states/editions), and these two different plans are definitely not noted within Wilton-Ely's recent Giovanni Battista Piranesi - The Complete Etchings. Moreover, I believe I discovered something that no other architect, architectural historian, or art historian had noticed before. I then quickly scanned the rest of the plan to see if any other differences existed, and, sure enough, the Circus Agonalis is likewise different than the plan commonly reproduced. On 4 April 2000, I finally returned to Penn's Fine Arts Library to document the two different Ichnographia via tracings and taking digital images:

The image above left is the Circus of Caligula and Nero as the Ichnographia is commonly reproduced. The image above right is the Circus of Caligula and Nero as it appears within the University of Pennsylvania's (original) copy of the Campo Marzio.

The image above left is the Circus Agonalia as the Ichnographia is commonly reproduced. The image above right is the Circus Agonalia as it appears within the University of Pennsylvania's (original) copy of the Campo Marzio.

The differing plans raise several questions:

Did Piranesi himself make these changes, or did perhaps his son Francesco, and if Piranesi made them, then why?

Which set of plans were 'drawn' first?

Does this 'change of plan' carry any possible semiotic or symbolic message regarding the Ichnographia's larger meaning?

Does this physical evidence offer any indication of Piranesi's 'design' method?

|