| |

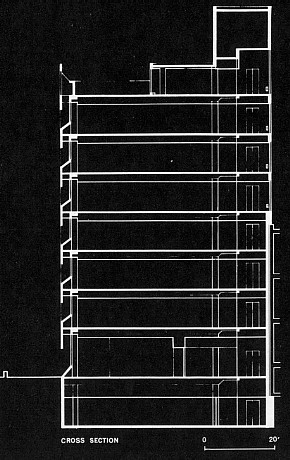

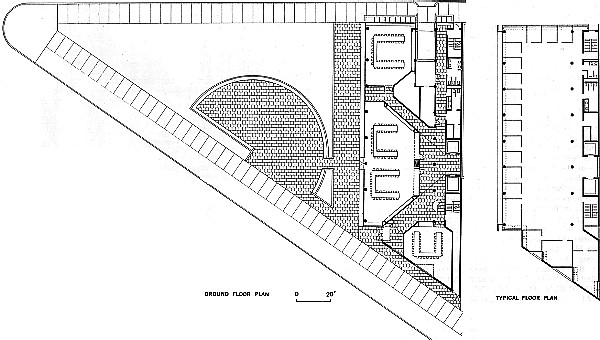

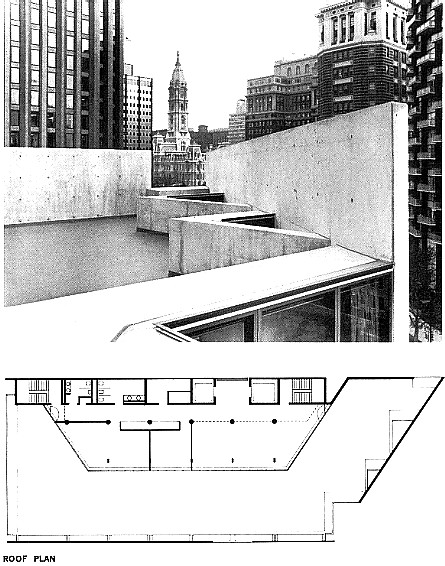

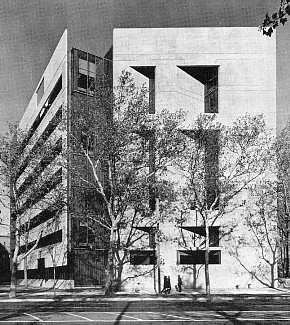

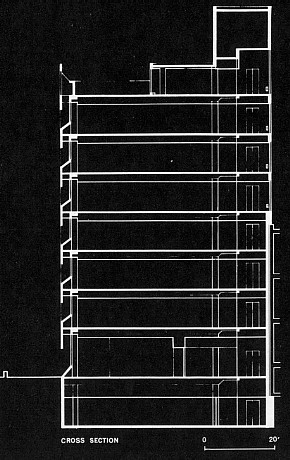

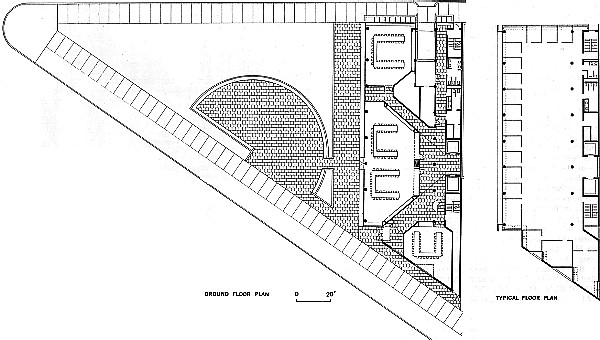

The three very different fronts on the north, west, and south respond to lighting conditions and--in the case of the bearing wall on the south--to structural demands. The building section shows duct space under the angular planes below the west windows; at the ground, one of these duct enclosures marks the property line along the park to the west. The architects' proposals for this park have not been adopted.

| |

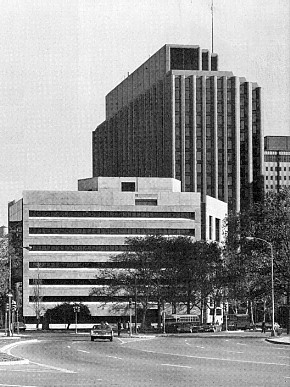

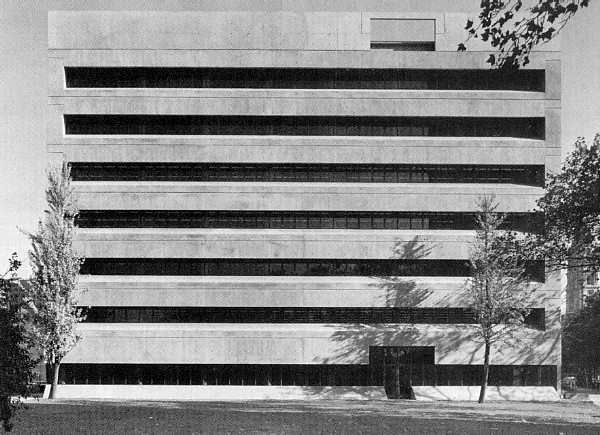

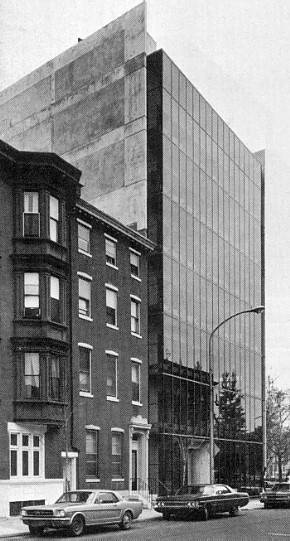

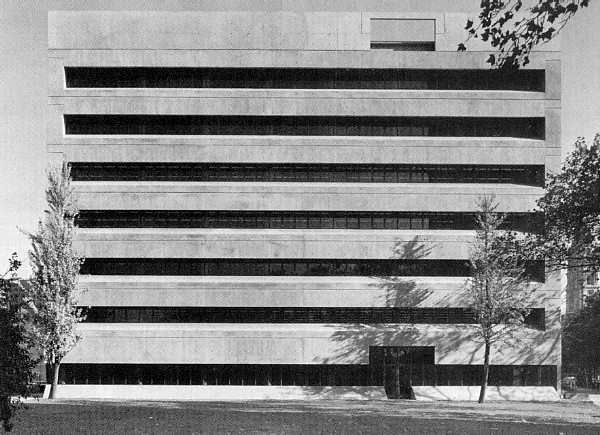

A building seen across an extensive open space had to present a strong image, if it was to be noticeable at all. Giurgola observes that a strong building form was needed at this point "in order to prop up all those giants around it"--those taller, bulkier, but rather amorphous piles that line the parkway to the east. And he stresses that no building is ever an isolated event.

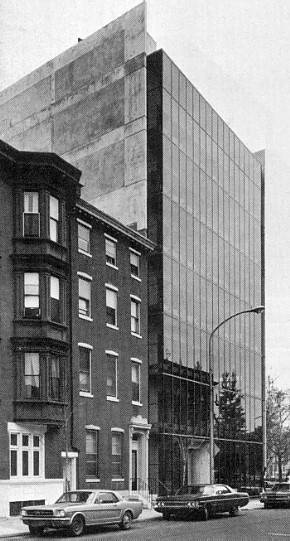

And it was the location, of course, that determined the widely differing treatment of the building's three exposed walls. On the north side, where direct sun is a minor problem, the whole facade is of gray-tinted glass in thin aluminum frames, allowing floor-to-ceiling views out over the roofs of the cathedral across the street.

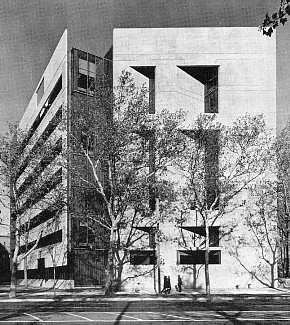

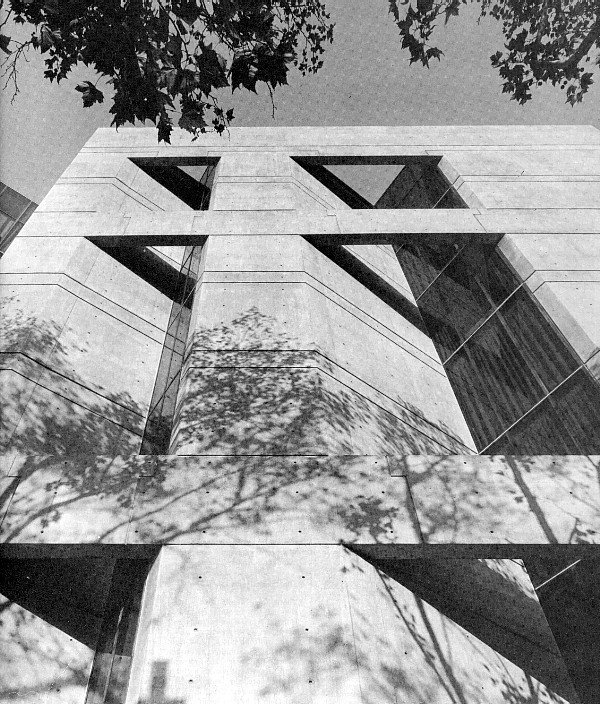

On the west, the urge to give office floors full exposure to a panoramic view and the need to protect them from west sun led to the design of the concrete screen, with its horizontal openings set about 1 ft. below the corresponding windows. Even though conventional wisdom calls for vertical sun-baffles on west walls, the architects claim that this horizontal design gives better protection against the high summer sun, which is most critical, and cuts out sky glare as well. The fact that this whole screen is suspended from the floor slabs is pointedly expressed on the exterior by detaching it from the ground.

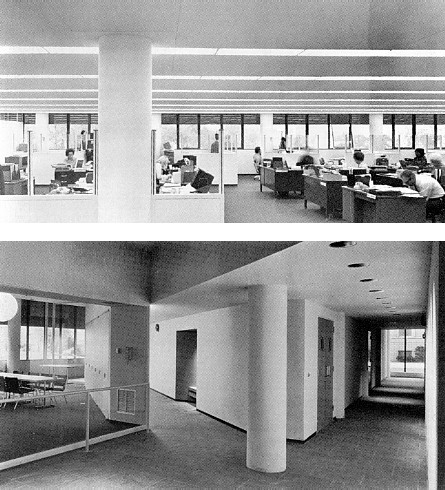

Conditions on the south wall called for sun protection, too, but it took a very different form. A bearing wall was needed here, to pick up loads from the column-and-beam concrete frame where it is cut off at an odd angle. Windows on this side are set into recesses whose walls line up with the 3-ft.-square grid of interior partitions and lighting. Projecting corners of the building provide enough sun control here, without special shading devices.

One obvious question comes up concerning the facades: why are the two very different screens on the south and west sides--one supporting the structure and the other suspended from it--both made of cast-in-place concrete? Two reasons, replies Giurgola:

1. to preserve the unity of the building. (The sides may differ, but the inner plane is always of glass, the outer one of cast-in-place concrete.)

2. because concrete was readily "moldable" to meet complex needs. (The west screen is "not just a plane," but folds back around the windows and provides duct spaces behind the angled planes at the sills.)

And the plane of concrete gives the west front the visual solidity the building needs for its position in the cityscape. A screen composed of smaller-scaled elements would not have read as one unified plane from a distance, as this screen definitely does. Yet somehow the horizontal baffles, streaking across the facade with so little apparent support, look inherently unstable--like a giant venetian blind. And the unbroken horizontal lines--while they help distinguish this building from its neighbors--contrast so strongly with other parts of the same building that it tends to break apart visually; Giurgola knows this, of course, and is willing to chance it.

|