|

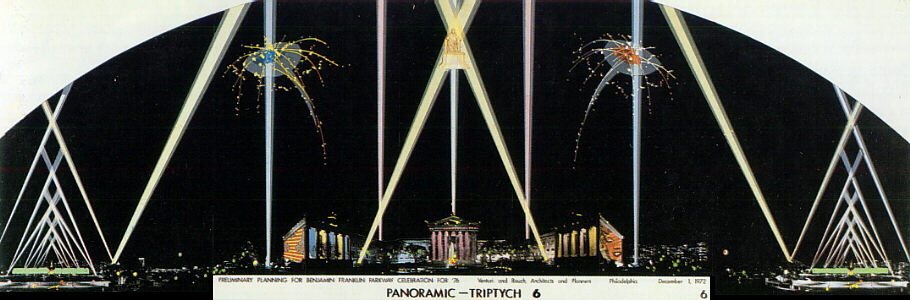

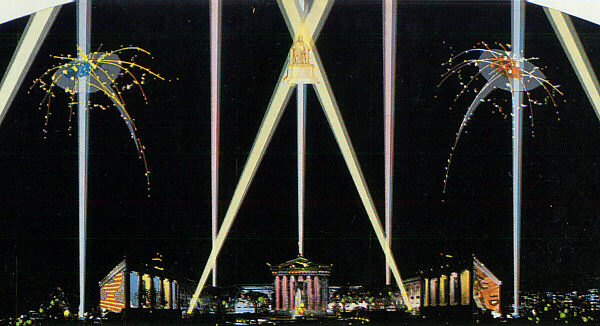

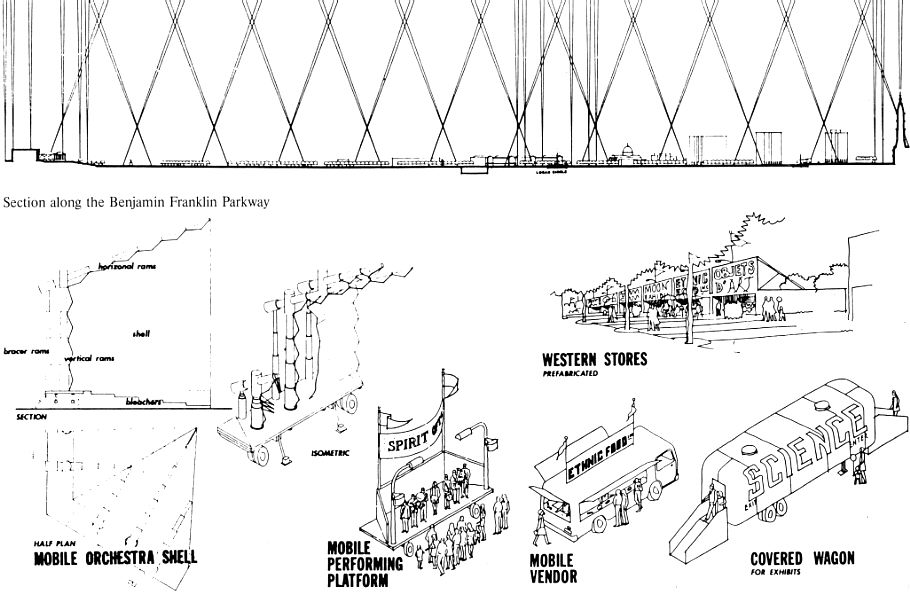

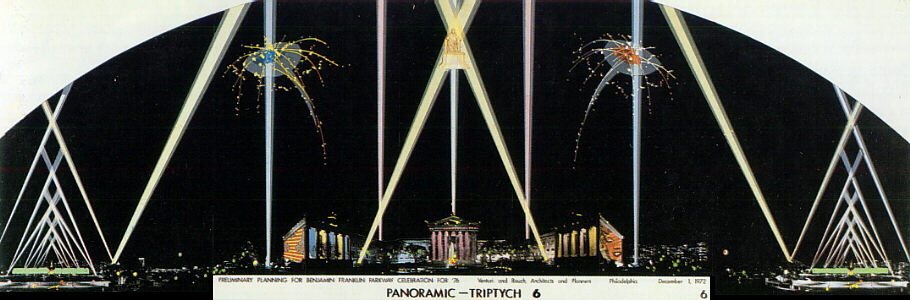

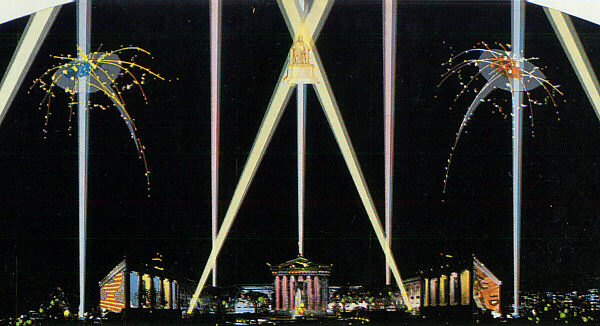

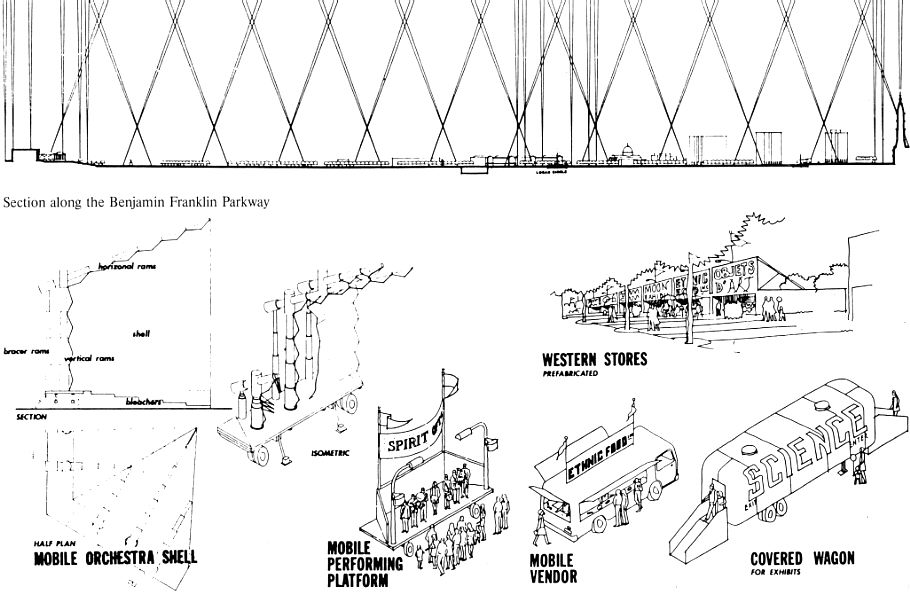

Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976

Project for celebration and exhibition architecture for the American Bicentennial, Philadelphia (1972)

In charge: Robert Venturi

Project manager: Steven Izenour

with W.G. Clark

The Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia's monumental axis, is a major work of the "City-Beautiful" movement. The project called for keeping this "Champs-Elysée" intact and for organizing a number of activities to enhance its vitality and glamour. The architects concluded that the Parkway's ceremonial character could hardly be improved upon by day. By night, however, moving lights, not available when the street was designed, could be used to dramatize this setting.

The architects also proposed that movable kiosks, booths, a system of signs, stages for improvised concerts, and other features be erected along both sides of the monumental boulevard.

Stanilaus von Moos, Venturi, Rauch & Scott Brown: Buildings and Projects (New York: Rizzoli, 1987), p. 98.

| |

See also: The Bicentennial Commemoration 1976

|

|

| |

It is not aleatory then that the already outworn images of Archigram, or the artificial and willful ironies of Robert Venturi or of Hans Hollein simultaneously amplify and restrict the field of intervention of architecture. They amplify it insofar as they understand that space solely as a network of superstructures.

There is, however, a result to this which emerges in projects such as that by Venturi and Rauch for the American Bicentennial Celebration* in Philadelphia. Here, there is no longer a desire to communicate; the architecture is dissolved into an unstructured system of ephemeral signals. Instead of communication, there is a flux of information; instead of an architecture as language, there is an attempt to reduce it to a mass-medium, without any ideological residue; instead of an anxious effort to restructure the urban system, there is a disenchanted acceptance of reality, becoming an excess of purest cynicism. (Excess, after all, always carries a critical connotation.) In this fashion, Venturi, placing himself within an exclusively linguistic framework, has reached a radical devaluation of the language itself. The meaning of the Plakatwelt, of the world of publicity, is closed in on itself. He thereby achieves the symmetrically opposed result of that metaphysical retrieval of a "being" of architecture, extracted from the flux of existence. For Venturi, it is the non-utilization of language itself, having discovered that its intrinsic ambiguity, once having made contact with reality, makes illusory any and all pretexts of autonomy.

Manfredo Tafuri, "L'Architecture dans le Boudoir: The language of criticism and the criticism of language" (1974).

*The Venturi & Rauch project used to illustrate Tafuri's point is the International Bicentennial Exposition Master Plan (1971). Tafuri's words, however, seem to relate to both the International Bicentennial Exposition Master Plan and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 (1972)--two distinct projects each for a different site in Philadelphia. Tafuri references the "American Bicentennial Celebration" to a feature of what is actually both Venturi & Rauch projects within a 1973 issue of L'architecture d'aujourd'hui magazine where it is easy to mistake the two projects as one single work. It's interesting then that Tafuri's salient point about an architecture "dissolved into an unstructured system of ephemeral signals" is based upon two distinct projects misperceived as one.

|

| |

2012.09.03 16:52

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

2026 Vision?

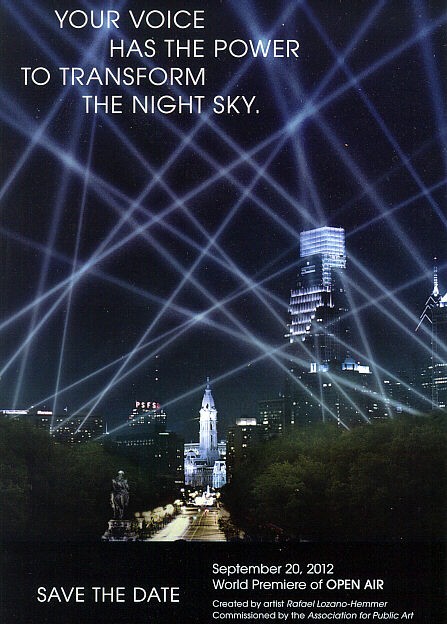

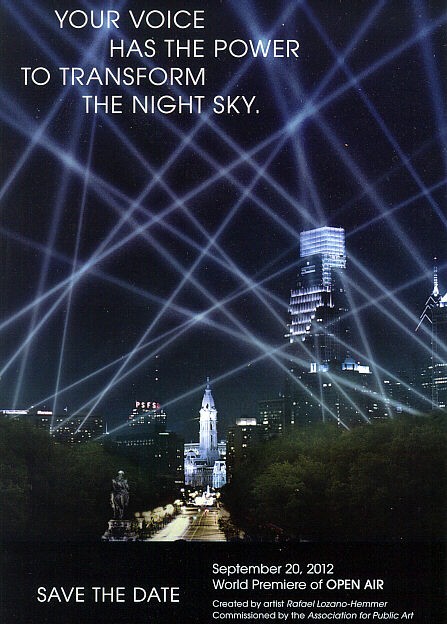

This past Saturday I received a postcard inviting me to the world premiere of Open Air:

This fall, head to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and take part in the largest crowd-sourced public art experience ever seen in Philadelphia. Open Air will employ 24 searchlights, a free mobile app, and your voice and GPS position to transform the night sky. Created for Philadelphia by internationally acclaimed artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer.

I was immediately reminded of Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 (1 December 1972).

Today I went online to see if Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 is anywhere mentioned as inspiration for Open Air, and there is no 'official' mention of Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 in conjunction with Open Air except a commentor to one of the Open Air news posts, Andy Blanka, did mention that Venturi & Rauch had already designed something similar. In any case and forty years later, Open Air will be an un-official tribute to the ideas of Venturi, Rauch, Scott Brown and Izenour (who did the above drawings).

Ideas for the Bicentennial were first published within the October 1969 issue of The Architectural Forum--"The Bicentennial Commemoration 1976"--a rare piece of writing where Denise Scott Brown precedes Robert Venturi as co-author. Seen now in retrospect, many of the ideas proposed were ground-breaking and indeed influential in the long run, and still relevant today with regard to current notions of architecture and advocacy. To offer one flavor of the piece I parsed out the sentences that contain the words 'little' and then the sentences that contain the word 'big':

"It is significant that Expo 67, hailed as a triumph, produced little innovation in architecture or structure."

"Still very much employed and perhaps even more challenged, since now their ingenuity would be taxed to make much out of the little available for building, to make meaningful in built structures the serious aims of the nation, and on top of this to make our show fun, seductive and delightful."

"The Commemoration should serve, starting now, as a major aid to economic development of the black community, otherwise we shall have little to celebrate in 1976."

"Why should Little Upper Begonia strive to show us its plastic factory when it has so much to say on the harnessing of teen-age revolt or on the housing of rural migrants?"

"An Expo based on interaction of people in meeting places spread over several cities could look a little low."

"We recommend, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

"We advocate, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

There is an authors' note at the end of the piece:

We owe much in the development of our ideas to Mr. Tom Wolfe (who coined the phrase "electrographic architecture"), to Mr. David A. Crane, to members of the Philadelphia Bicentennial International Exposition Planning Group, and to the Philadelphia Citizens' Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community, and all their advisors.

This brings to mind a curious footnote within Charles Jencks' The Story of Post-Modernism (2011):

Tom Wolfe lampooned architects' inability to reach the exuberance of Las Vegas sign artists, or 'Electrographic Architecture', in many articles. One key essay, republished in his collection Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1965, was written in his neo-hysterical style--'Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas!!!' Tim Vreeland has told me that when Venturi and Scott Brown were visiting Albuquerque circa 1968, he put a copy of Wolfe's book on the bedside table, and the couple were so impressed they drove off to see Las Vegas the next day. Their own shift in taste-culture towards commercial vernacular and Route 66, culminated first in an article, 'A Significance for A&P Parking Lots' (1968) and then the whole argument, Learning from Las Vegas, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA/London), 1972. Thus the Las Vegas polemic may date from Wolfe's humorous assault on professional taste, and that he too was to carry on with another attack on Minimalist Modernism, From Bauhaus to Our House, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1981. Reyner Banham took the Las Vegas sign artists in another direction, towards the dematerialized city of electronics, light, and environmental control. His The Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment, Architectural Press (London), 1969, inverts the Corbusian definition of architecture--'pure forms seen in sunlight'--to 'coloured light seen in impure forms'.

To clear up some of the chronology suggested above:

1965: On her way to California to teach in the School of Environmental Design at Berkeley for the spring semester, Scott Brown stops off in Las Vegas. That summer she travels in the southwest [including Albuquerque?]. In September, Scott Brown moves to Los Angeles and accepts the position of co-chair of the Urban Design Program at UCLA, where she remains through 1967. She recruits Venturi to act as a visiting critic.

1966: Scott Brown invites Venturi to visit Las Vegas with her for a four-day trip. In November the two travel the Las Vegas strip, from casino to casino, being alternately "appalled and fascinated" by what they see. ["Next I was taken to Las Vegas in 1966 by Denise Scott Brown--prepared a little by Tom Wolfe and a lot by Baroque Rome. Out of that trip came our studio at Yale and then our book Learning from Las Vegas."]

Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture is published by the Museum of Modern Art as the first in an intended series of occasional papers addressing issues of architecture and design (actual distribution is not until March 1967).

I doubt very much I'll actually see Open Air in person, but I could easily make a virtual model of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976. Or better yet, I should start publishing my ideas for the Semiquincentennial!

|