2013.08.29 12:30

Learning from Learning from Las Vegas (again)

Here is an extended passage from the 'Introduction' of Tom Wolfe's The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965):

"Jane Holzer--and the Baby Jane syndrome--there's nothing freakish about it. Baby Jane is the hyper-version of a whole new style of life in America. I think she is a very profound symbol. But she is not the super-hyper-version. The super-hyper-version is Las Vegas. I call Las Vegas the Versailles of America, and for specific reasons. Las Vegas happened to be created after the war, with war money, by gangsters. Gangsters happened to be the first uneducated . . . but more to the point, unaristocratic, outside of the aristocratic tradition . . . the first uneducated prole-petty-burgher Americans to have enough money to build a monument to their style of life. They built in an isolated spot, Las Vegas, out in the desert, just like Louis XIV, the Sun King, who purposely went outside of Paris, into the countryside, to create a fantastic baroque environment to celebrate his rule. It is no accident that Las Vegas and Versailles are the only two architecturally uniform cities in Western history. The important thing about the building of Las Vegas is not that the builders were gangsters but that they were proles. They celebrated, very early, the new style of life of America--using the money pumped in by the war to show a prole vision . . . Glamor! . . . of style. The usual thing has happened, of course. Because it is prole, it gets ignored, except on the most sensational level. Yet long after Las Vegas' influence as a gambling heaven has gone, Las Vegas' forms and symbols will be influencing American life. The fantastic skyline! Las Vegas' neon sculpture, its fantastic fifteen-story-high display signs, parabolas, boomerangs, rhomboids, trapazoids and all the rest of it, are already the staple design of the American landscape outside of the oldest parts of the oldest cities. They are all over every suburb, every subdivision, every highway . . . every hamlet, as it were, the new crossroads, spiraling Servicenter signs. They are the new landmarks of America, the new guideposts, the new way Americans get their bearings. And yet what do we know about these signs, these incredible pieces of neon sculpture, and what kind of impact they have on people? Nobody seems to know the first thing about it, not even the men who design them. I hunted out some of the great sign makers of Las Vegas, men who design for the Young Electric Sign Co., and the Federal Sign and Signal Corporation--and marvelous!--they come from completely outside the art history tradition of the design schools of the Eastern Universities. I remember talking with this one designer, Ted Blaney, from Federal, their chief designer, in the cocktails lounge of the Dunes Hotel on "The Strip." I showed him a shape, a boomerang shape, that one sees all over Las Vegas, in small signs, huge signs, huge things like the archway entrance to the Desert Inn--it is not an arch, really, but this huge boomerang shape--and I ask him what they, the men who design these things, call it.

Ted was a stocky little guy, very sunburnt, with a pencil mustache and a Texas string tie, the kind that has string sticking through some kind of silver dollar or something situated at the throat. He talked slowly and he had a way of furling his eyebrows around his nose when he did mental calculations such as figuring out this boomerang shape.

He stared at the shape, which he and his brothers in the art have created over and over and over, over, over and over and over in Las Vegas, and finally he said,

"Well, that's what we call--what we sort of call--'free form.'"

Free form! Marvelous! No hung-up old art history words for these guys. America's first unconscious avant-garde! The hell with Mondrian, whoever the hell he is. The hell with Moholy-Nagy, if anybody ever heard of him. Artists for the new age, sculptors for the new style and new money of the . . . Yah! lower orders. The new sensibility--Baby baby baby where did our love go?--the new world, submerged so long, invisible, and new arising, slippery, shiny, electric--Super Scuba-man!--out of the vinyl deeps."

- - - - -

There's no question that Wolfe (already) learned something very new from Las Vegas. And there's no question that this passage precurses and inspired Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour. What's interesting now is the difference between Wolfe's focus and V,SB&I's focus--a journalistic focus versus an academic focus, sort of. There is also the difference that V,SB&I probably felt they had to introduce so as not be 'copying' Wolfe. For example, V,SB&I do not exactly pursue the study of Las Vegas as a rare case of an "architecturally uniform city in Western history." Right now, I kind of wish they had.

| |

2013.09.08 11:18

Learning from Learning from Las Vegas (again)

Here are the relevant passage from Tom Wolfe's "Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas! ! ! !" in The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965):

He had been rolling up and down the incredible electric-sign gauntlet of Las Vegas' Strip, U.S. Route 91, where the neon and the par lamps--bubbling, spiraling, rocketing, and exploding in sunbursts ten stories high out in the middle of the desert--celebrate one-story casinos. . . .

Actually, it is part of something rare and rather grand: a combination of baroque stimuli that brings to mind the bronze gongs, no larger than a blue plate, that Louis XIV, his ruff collars larded with the lint of the foul Old City of Byzantium, personally hunted out in the bazaars of Asia Minor to provide exotic acoustics for his new palace outside Paris. . . .

The crowd and band sounds are not very extraordinary, of course. But Las Vegas' Muzak is. Muzak pervades Las Vegas from the time you walk into the airport upon landing to the last time you leave the casinos. It is piped out to the swimming pool. It is in the drugstores. It is as if there were a communal fear that someone, somewhere in Las Vegas, was going to left with a totally vacant minute on his hands.

Las Vegas has succeeded in wiring an entire city with this electronic stimulation, day and night, out in the middle of the desert. In the automobile I rented, the radio could not be turned off, no matter which dial you went after. I drove for days in a happy burble of Action Checkpoint News, "Monkey No. 9," "Donna, Donna, the Prima Donna," and picking-and-singing jingles for the Frontier Bank and the Fremont Hotel.

One can see the magnitude of achievement. Las Vegas takes what in other American towns is but a quixotic inflammation of the senses for some poor salary mule in the brief interval between the flagstone rambler and the automatic elevator downtown and magnifies it, foliates it, embellishes it into an institution.

For example, Las Vegas is the only town in the world whose skyline is made up neither of buildings, like New York, nor of trees, like Wilburnham, Massachusetts, but signs. One can look at Las Vegas from a mile away on Route 91 and see no buildings, no trees, only signs. But such signs! They tower. They revolve, they oscillate, they sour in shapes before which the existing vocabulary of art history is helpless. I can only attempt to supply names--Boomerang, Modern, Palette Curvilinear, Flash Gordan Ming-Alert Spiral, McDonald's Hamburger Parabola, Mint Casino Elliptical, Miami Beach Kidney. Las Vegas' sign makers work so far out beyond the frontiers of conventional studio art that they have no names themselves for the forms they create. Vaughan Cannon, one of those tall, blonde Westerners, the builders of places like Las Vegas and Los Angeles, whose eyes seem to have been bleached by the sun, is in the back shop of the Young Electric Sign Company out on east Charleston Boulevard with Herman Boernge, one of his designers, looking at the model they have prepared for the Lucky Strike Casino sign, and Cannon points to where the sign's two great curving faces meet to form a narrow vertical face and says:

"Well, here we are again--what do we call that?"

"I don't know," says Boernge. "It's sort of a news effect. Call it a nose."

Okay, call it a nose, but it rises sixteen stories high above a two-story building. In Las Vegas no farseeing entrepreneur buys a sign to fit a building he owns. He rebuilds the building to support the biggest sign he can get up the money for and, if necessary, changes the name. The Lucky Strike Casino today is the Lucky Casino, which fits better when recorded in sixteen stories of flaming peach and incandescent yellow in the middle of the Mojave Desert. In the Young Electric Sign Co. era signs have become the architecture of Las Vegas, and the most whimsical, Yale-seminar-frenzied devises of the two late geniuses of Baroque Modern, Frank Lloyd Wright and Eero Saarinen, seem rather stuffy business, like a jest at a faculty meeting, compared to it. Men like Boernge, Kermit Wayne, Ben Mitchem and Jack Larsen, formerly an artist for Disney, are the designer-sculptor geniuses of Las Vegas, but their motifs have been carried faithfully throughout the town by lesser men, for gasoline stations, motels, funeral parlors, churches, public buildings, flophouses and sauna baths.

- - - - - - - -

Being now fully aware of the role Wolfe played in the making the Learning from Las Vegas, my view of the VSBI project has changed. For a start, Learning from Las Vegas no longer seems lively and unique, rather now a bit cold and clinical. Furthermore, Learning from Las Vegas now feels even more agenda driven than specifically about Las Vegas, per se. It's odd (for me, at least) to now realize that Learning from Las Vegas could have been legitimately different than is it, could have been better even.

Note to self: Remember the connection between Wolfe's list of new dances and what are probably the only house designs named for a flash-in-the-pan 1960s dance craze.

| |

2013.09.20 18:19

Interesting quote

The entire quotation reads:

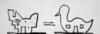

"When Modern architects righteously abandoned ornament on buildings, they unconsciously designed buildings that were ornament. In promoting Space and Articulation over symbolism and ornament, they distorted the whole building into a duck. They substituted for the innocent and inexpensive practice of applied decoration on a conventional shed the rather cynical and expensive distortion of program and structure to promote a duck; minimegastructures are mostly ducks.

It is now time to reevaluate the once-horrifying statement of John Ruskin that architecture is the decoration of construction, but we should append the warning of Pugin: It is all right to decorate construction but never construct decoration."

This is essentially the last paragraph of Learning from Las Vegas, specifically the end of "Theory of Ugly and Ordinary and Related and Contrary Theories" (page 163, 2nd edition).

It really didn't matter whether construction was decorated or decoration was constructed, and it still doesn't matter. Architects can design in any way (or style) they want.

2015.06.19 10:33

Are diagrams in architecture bullshit and ditto for process?

"The Duck and the Decorated Shed" came within a year or two after the completed construction of Guild House (1961-66), coinciding with the marriage of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown--23 July 1967.

Before Guild House there is George Howe's Maurice Speiser House (1933) and Louis Kahn's Congregation Ahavath Israel (1935-37) (Venturi's immediate Philadelphia architecture legacy) and Moretti's Casa "Il Girasole (1947-50) (effect of Venturi's study in Rome 1954-56).

|