13 July 1778 Monday

. . . . . .

Artifacts of the Bianconi vs Piranesi 'Circus of Caracalla' affair 1772-1789

Giovanni Lodovico Bianconi's "Elogio Storico del Cavaliere Giovanni Battista Piranesi Celebre Antiquario ed Incisore de Roma" (1779)

paragraph one

Chi potesse scrivere con libertà e decenza la vita tumultuosa di Giambattista Piranesi, farebbe un libro non meno gustoso, né meno ghiotto di quello che di sé stesso scrisse il famoso Benvenuto Cellini. Noi ci limiteremo a darne un breve saggio come si potrà, nel quale, se non diremo tutte le verità, si cercherà almeno che tutto quello che diremo sia vero.

Anyone who could write the tumultuous life of Giambattista Piranesi with freedom and decency would make a book no less tasty, nor less greedy than the one that the famous Benvenuto Cellini wrote about himself. We will limit ourselves to giving as brief an essay as possible, in which, if we will not tell all the truths, we will at least try to make sure that everything we say is true.

paragraph two

Nacque questo singolar uomo, per quanto egli dicea, da uno scarpellino in Venezia nel 1721. Invogliossi di far l’architetto, e ne prese i primi rudimenti da un certo Scalfaroto a noi Romani sconosciuto, ma che dovea essere uomo di qualche merito, se sono giuste le lodi che gli dava il Piranesi. Avea questi diciotto anni appena quando determinossi a venire alla fonte delle bell’arti, cioè alla gran Roma, ove studiò la prospettiva sotto i Valeriani, pittori teatrali allora in qualche voga. I celeri progressi del Piranesi non lasciarono molto da fare ai maestri, perché ben presto essi non si trovarono più in istato di tenergli dietro. Innamorossi tutt’a un tratto dell’arte d’incidere in rame, e andò ad impararla dal cavalier Vasi, siciliano domiciliato in Roma, e qui pure fece passi grandissimi. Per dare saggio de’ suoi studi incise varie prospettive, e per

acquistarsi un valido Mecenate dedicolle a non so qual ricco muratore, il quale, non curandosi di questi onori, non lo ricompensò punto; quindi fu ben presto abbandonato dal suo cliente. Accorgendosi dappoi il Piranesi che l’incisione di queste sue fatiche non era molto plausibile, il suo naturale sospettoso gli fece credere che ciò nascesse dal Vasi, che per gelosia gli nascondesse il vero segreto di dar l’acqua forte. Infuriatosi adunque un giorno volle ammazzare il maestro che con buone maniere lo placò, ma liberò la sua scuola il più presto che potè da un discepolo così pericoloso, ringraziandone ben di cuore Iddio. Partì allora co’ suoi rami molto di mal umore il Piranesi, e ritornò a Venezia per ivi fermarsi a far l’architetto. Tale secondo tentativo non gli riuscì meglio del primo, perché non ebbe veruna commissione; quindi limitossi a vendere le sue prospettive alla meglio, per raccoglierne danari e ritornarsene a Roma a tentar nuova strada. Qui giunto si unì col celebre Polenzani incisore

veneziano, fatto venire poco prima in Roma non so da chi solamente per incidere certe carte geografiche, benché avesse maravigliose disposizioni per

qualunque altra parte ancora delle belle arti. Il Polenzani intanto s’era invogliato di studiare la figura, e seco lui cominciolla a studiare anche il Piranesi, il quale, disegnando improbamente quasi tutta la notte, non prendea che poche ore di sonno sopra un misero sacco di paglia, che era forse il miglior mobile che egli avesse in casa. In tale stato visse qualche tempo nelle più grandi angustie il Piranesi, ma in vece di studiare il nudo, e le più bellestatue della Grecia che abbiamo qui, e che sono la sola buona strada per imparare, egli si mise a disegnare i più sgangherati storpi e gobbi, che vedeva il giorno per Roma, caritatevole ricevitrice mai sempre di tutto ciò che in questo genere produce di più elegante l’Europa. Amava ancora a disegnare gambe impiagate, braccia rotte, e cudrioni magagnati, e quand’egli trovava per le Chiese uno di questi spettacoli a lui pareva d’aver trovato un nuovo Apollo di Belvedere, o un Laocoonte, e correva tosto a casa a disegnarselo. Chi ha veduta questa singolare raccolta asserisce essere essa la più salutare meditazione delle miserie umane. Quando voleva innalzarsi, e darsi quasi all’eroico, disegnava cose mangiative, come sarebbero pezzi di carne da macello, teste di porco o di capretto; bisogna però confessare che faceva tali cose maravigliosamente bene. Alcuni di questi disegni si conservano presso il Senatore di Roma, principe Rezzonico, dalla cui autorevole protezione ha sempre tratto grandissimo vantaggio ed onore fino agli ultimi giorni della sua vita il nostro artefice.

This singular man was born, according to what he said, from a shoemaker in Venice in 1721. He wanted to be an architect, and he took the first rudiments from a certain Scalfaroto, unknown to us Romans, but who must have been a man of some merit, if the praise that Piranesi gave him is right. He was just eighteen years old when he determined to come to the source of the fine arts, that is, to great Rome, where he studied perspective under the Valerians, theatrical painters then in vogue. Piranesi's rapid progress did not leave the masters much to do, because soon they no longer found themselves in a position to keep up with him. He fell in love all of a sudden with the art of copper engraving, and went to learn it from Cavalier Vasi, a Sicilian domiciled in Rome, and here he also made great strides. To give evidence of his studies he engraved various perspectives, and for acquire a valid Maecenas dedicated to I don't know what rich mason, who, not caring about these honors, did not reward him at all; so he was soon abandoned by his client. Piranesi later realizing that the engraving of these labors of his was not very plausible, his natural suspicion led him to believe that this originated from Vasi, who out of jealousy was hiding from him the true secret of giving strong water. Enraged, therefore, one day he wanted to kill the teacher who placated him with good manners, but freed his school as soon as he could from such a dangerous disciple, thanking God very much. Piranesi then left with his branches in a very bad mood, and returned to Venice to stop there to work as an architect. This second attempt did not succeed him better than the first, because he received no commission; therefore he confined himself to selling his prospects as best he could, to collect money and return to Rome to try a new road. Here he joined the famous engraver Polenzani

Venetian, brought to Rome shortly before I don't know by whom only to engrave certain geographical maps, although he had marvelous dispositions for

any other part of the fine arts. In the meantime, Polenzani had been tempted to study the figure, and with him he also began to study Piranesi, who, improbably drawing almost all night, only slept a few hours on a miserable straw sack, which was perhaps the best piece of furniture he had at home. In this state Piranesi lived for some time in the greatest anguish, but instead of studying the nude, and the most beautiful statues of Greece that we have here, and which are the only good way to learn, he began to draw the most ramshackle cripples and hunchbacks, who saw the day for Rome, always a charitable receiver of all that Europe produces most elegantly in this genre. He still loved to draw sprained legs, broken arms, and battered cudrions, and when he found one of these shows in the churches, it seemed to him that he had found a new Apollo of Belvedere, or a Laocoon, and he immediately ran home to draw it. . Anyone who has seen this singular collection asserts that it is the healthiest meditation on human misery. When he wanted to raise himself, and give himself almost to the heroic, he drew eating things, such as pieces of meat for slaughter, pig or kid heads; but it must be confessed that he did such things marvelously well. Some of these drawings are kept by the Senator of Rome, Prince Rezzonico, from whose authoritative protection our architect has always drawn great advantage and honor until the last days of his life.

46 y.o. Francesco Piranesi 1804

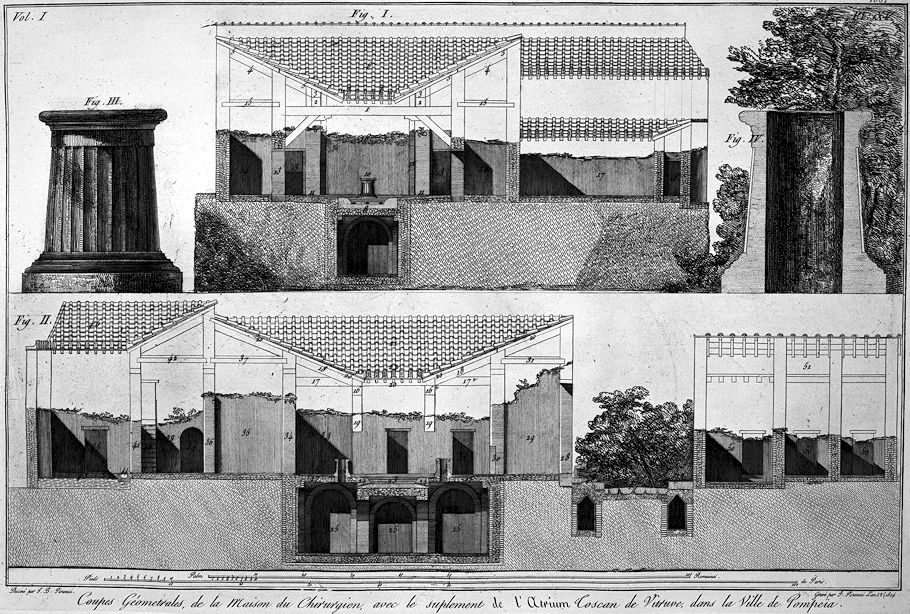

Le Antichità della Magna Grecia Parte I

Geometric Sections, of the House of the Surgeon, with the addition of the Tuscan Atrium by Vitruvius, in the City of Pompeii.

Drawn by G.B. Piranesi

Engraved by F. Piranesi Year 12 (1804)

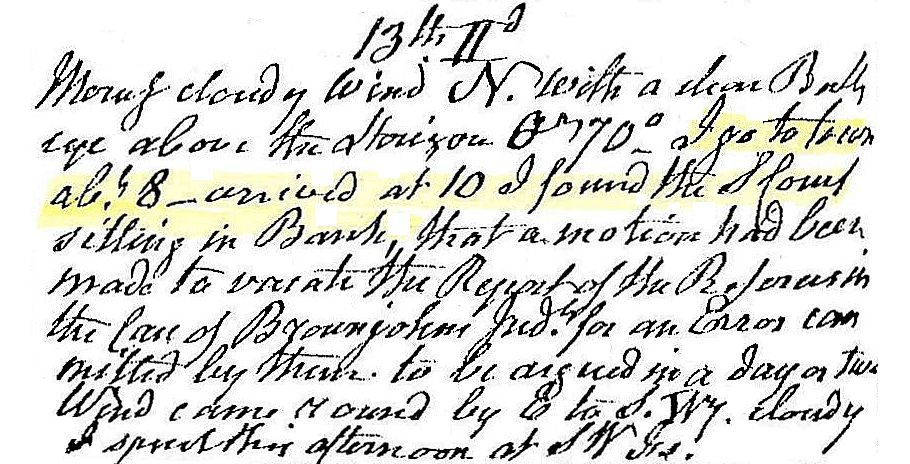

13 July 1812 Monday

Morning cloudy, wind N with a clear bull's eye above the horizon, temperature 70°. I go to town about 8, arrived at 10. I found the S Court sitting in Bank, that a motion had been made to vacate the report of the referees of the case of Brownjohns Judgement[?] for an error committed by them to be argued in a day or two. Wind came round by E to SWerly, cloudy. I spent the afternoon at SWF's.

13 July 2003

Lucian and Helenopolis (or taking an historical bath)

On two separate occasions--lt-antiq posts--I have suggested the possibility of a personal relationship between St. Helena and St. Lucian. This speculation was based primarily on readings within Pohlsander's Helena: Empress And Saint where Lucian is referred to as Helena's favorite saint combined with historical reports that Constantine went to pray at the Basilica of St. Lucian at Helenopolis shortly before he (Constantine) died. I now wish to retract these suggestions and explain what I now content to be a more probable scenario.

Lucian died a martyr's death at Nicomedia 7 January 312. He was subsequently buried at Drepanum. Drepanum, today's Yalova, is directly due west and across the Gulf of Izmit from Nicomedia, today's Izmit. Legend has it that Lucian's body was tossed into the sea at Nicomedia, and that dolphins brought it to the shores of Drepanum. Helena at this time was most likely at Trier, within Constantine's court there, however, legend has it that Helena 'built' the Basilica of Lucian.

It is largely accepted today that Helena was born at Drepanum, but it is unlikely that she was anywhere within the Eastern Empire between 306 and late 324, while Constantine was (one of the) ruler(s) in the West. (Compare the plight of Prisca and Valaria, Diocletian's wife and daughter respectively, at the same time, and it becomes easy to figure that Helena would not have survived within the Eastern Empire without the direct protection of her son.)

My contention all along has been that Helena was the person responsible for organizing all the enormous church building in Rome between late 312 and 324, while Constantine was sole ruler in the West. Upon Constantine's rise to sole rulership of the entire Empire late 324, there are two indications that Helena too was then thereafter also in the East -- (1) when she was proclaimed Augusta, and (2) as one of the Imperial family members at the Council of Nicaea spring/summer 325. It is also my contention that Helena then went on to organize church building in the Holy Land after the Council of Nicaea and before the closing celebrations of Constantine's Vicennialia (sp?) at Rome 25 July 326. It was after the Council of Nicaea that Helena went to Drepanum, learned or already knew of Lucian's burial there, and thus ordered the building of a Basilica upon the grave site--this follows the same exact pattern of how the first basilicas were built in Rome, a pattern, moreover, repeated soon again in the Holy Land.

Some time between 326 and 336 Constantine renamed Drepanum as Helenopolis, and Helenopolis is today named Yalova. I did a web search of Yalova two days ago, and learned that the natural thermal baths at Yalova are the best/most renowned of the region. This fact interests me because Helena herself is credited with having reconstructed a bath-house/thermae in Rome, right near the Sessorian Palace where she lived. I wonder whether Helena was fond of thermal bathing because of her having been born at Drepanum.

Eusebius, in Vita Consantini book IV, chapter 61, in reference to the last month or so of Constantine's life writes:

"At first he [Constantine] experienced some slight bodily indisposition, which was soon followed by positive disease. In consequence of this he visited the hot baths of his own city [Constantinople]; and thence proceeded to that which bore the name of his mother [Helenopolis]. Here he passed some time in the church of the martyrs, and offered up supplications and prayers to God."

Nowhere does Eusebius state or even imply that Constantine went to Helenopolis specifically to pray at the Basilica of Lucian. In fact, Eusebius more or less tells us that Constantine specifically went to Helenopolis for its (famous) natural thermal baths. That Constantine also spent some time praying in "church" at Helenopolis seems only natural given that he sensed/feared he was soon to die.

I fear that the whole notion of Lucian being Helena's favorite saint arose mainly because subsequent historians and writers of legends lost sight of Drepanum's-Helenopolis'-Yalova's exceptional thermal baths. (I say exceptional because they indeed spring from one of Earth's most notorious fault lines.)

13 July 2023 Thursday

Web searching 'bianconi'-hits has become tiresome, yet I remain felling there are still more, important things to be found. It has turned out, however, that Bianconi was conducting a variety of antiquarian/archeological publishing affairs throughout his time in Rome. In a not so minor sense, this also meant Piranesi was no longer an unopposed leader in conducting Rome's antiquarian/archeological affairs. There was, indeed, an equality of quality to Bianconi's and Piranesi's respective works, but only Bianconi insisted on that reality, and that reality held until Piranesi insisted on the Circus of Caracalla's asymmetricality.

And here I thought I was going to write about Bianconi's Doctoring Piranesi - episode one - "Who's not an Imperial Piranesian?" It's an arresting spies tale; it's on lights camera action news and everything. A is for "always be" and B is for "alarmed."

In reality, I re-found Gregory T. Armstrong's "Constantine's Churches: Symbol and Structure." Re-reading it tomorrow; it's in JSAH March 1974. A great collection of the buildings and their early history that might really shine after some fixing. We'll see.

|