2012.09.12 18:52

fashion statements 2001-2012, what's next?

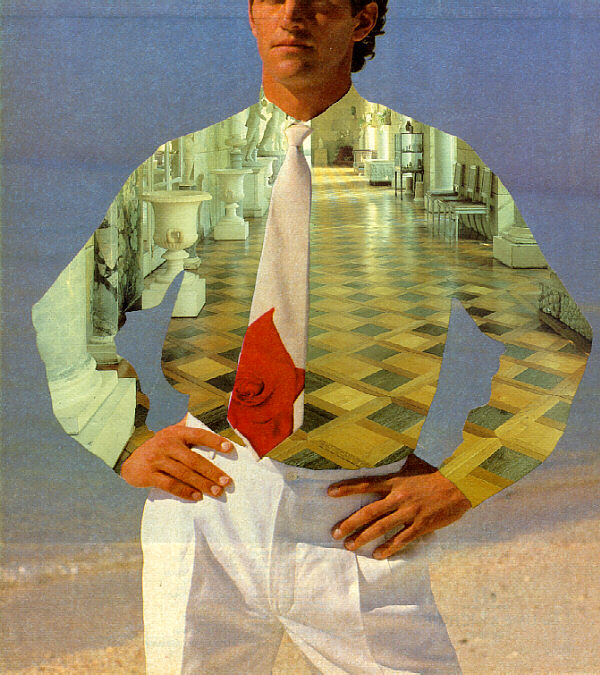

Stephen Lauf, Fashion Statement 002, 2001.06.20

Stephen Lauf, Fashion Statement 002, 2001.06.20

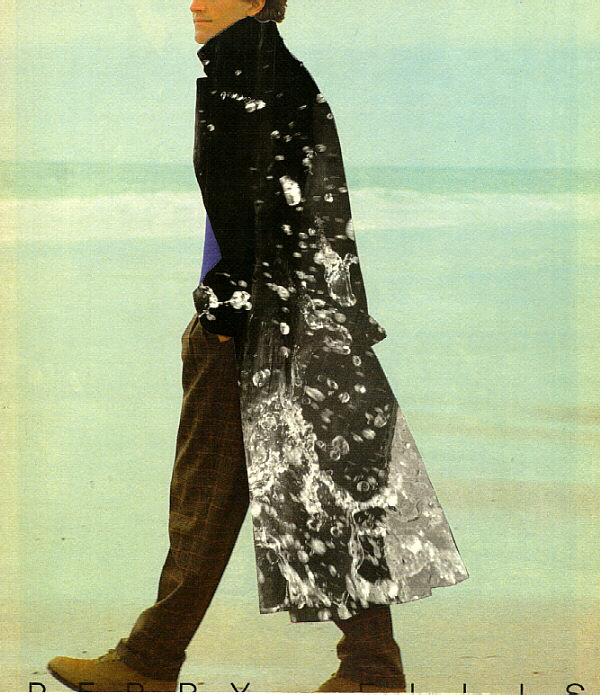

Stephen Lauf, Fashion Statement 005, 2001.06.20

Stephen Lauf, Fashion Statement 005, 2001.06.20

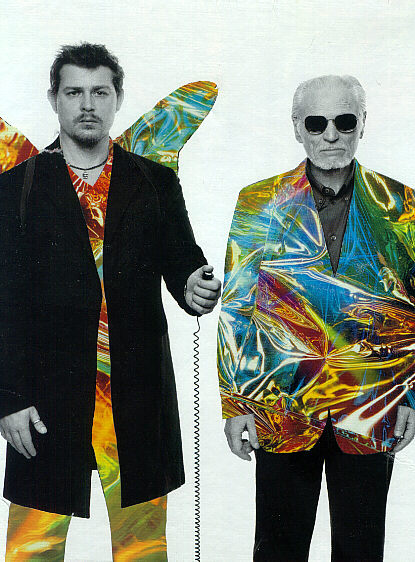

Stephen Lauf, Fashion Statement 008, 2006.02.25

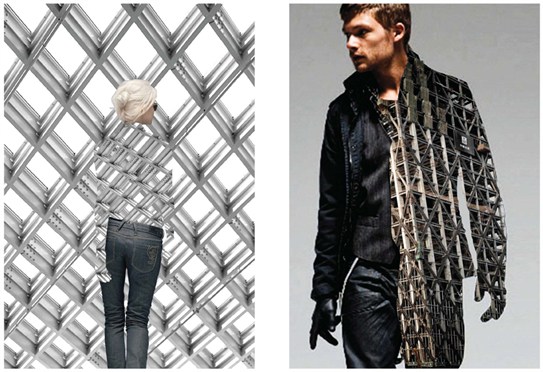

OMA, G Star RAW vs. OMA, 2012

If OMA/AMO is looking for some inspiration in 2014 or 2015, then may I suggest something I did in 2004.

| |

2012.09.04 13:18

Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing

Back in 1986, when I was Intergraph CAD system manager at the University of Pennsylvania's Graduate School of Fine Arts, one of the planning professors recently came back from China with research on some vernacular architecture. He was adament about drawing up some of his research using CAD, thus I had to quickly train him with at least the basics (which really wasn't my job). Anyway, the professor came in diligently to use his allotted time on the computer, and ultimately produced a pen plot of his 'drawings'. He was so proud, and stupid me didn't even get the reason why until a month later. The reason was obvious and right in front of me the whole time--the professor only had one hand with limited dexterity, and he couldn't draw except with the aid of a computer.

Odd that Michael Graves, who is himself now disabled and confined to a wheelchair, does not realize that computers have opened up the opportunity to draw to a whole range of people that couldn't do it otherwise.

2012.09.03 16:52

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

2026 Vision?

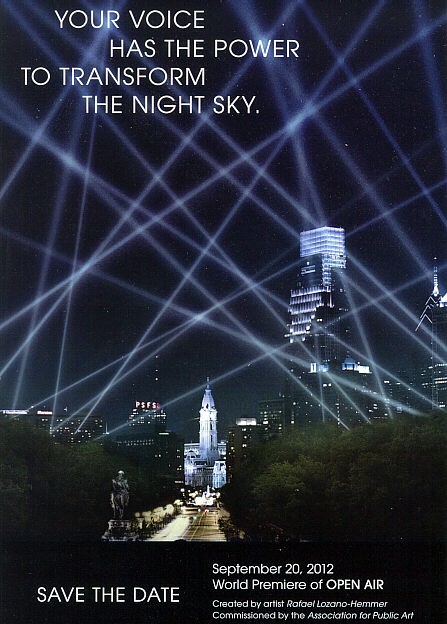

This past Saturday I received a postcard inviting me to the world premiere of Open Air:

This fall, head to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and take part in the largest crowd-sourced public art experience ever seen in Philadelphia. Open Air will employ 24 searchlights, a free mobile app, and your voice and GPS position to transform the night sky. Created for Philadelphia by internationally acclaimed artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer.

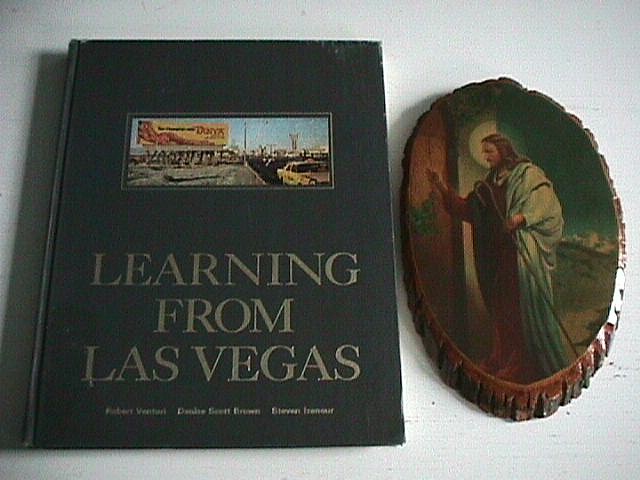

I was immediately reminded of Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 (1 December 1972).

Today I went online to see if Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 is anywhere mentioned as inspiration for Open Air, and there is no 'official' mention of Venturi & Rauch's Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976 in conjunction with Open Air except a commentor to one of the Open Air news posts, Andy Blanka, did mention that Venturi & Rauch had already designed something similar. In any case and forty years later, Open Air will be an un-official tribute to the ideas of Venturi, Rauch, Scott Brown and Izenour (who did the above drawings).

Ideas for the Bicentennial were first published within the October 1969 issue of The Architectural Forum--"The Bicentennial Commemoration 1976"--a rare piece of writing where Denise Scott Brown precedes Robert Venturi as co-author. Seen now in retrospect, many of the ideas proposed were ground-breaking and indeed influential in the long run, and still relevant today with regard to current notions of architecture and advocacy. To offer one flavor of the piece I parsed out the sentences that contain the words 'little' and then the sentences that contain the word 'big':

"It is significant that Expo 67, hailed as a triumph, produced little innovation in architecture or structure."

"Still very much employed and perhaps even more challenged, since now their ingenuity would be taxed to make much out of the little available for building, to make meaningful in built structures the serious aims of the nation, and on top of this to make our show fun, seductive and delightful."

"The Commemoration should serve, starting now, as a major aid to economic development of the black community, otherwise we shall have little to celebrate in 1976."

"Why should Little Upper Begonia strive to show us its plastic factory when it has so much to say on the harnessing of teen-age revolt or on the housing of rural migrants?"

"An Expo based on interaction of people in meeting places spread over several cities could look a little low."

"We recommend, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

"We advocate, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

There is an authors' note at the end of the piece:

We owe much in the development of our ideas to Mr. Tom Wolfe (who coined the phrase "electrographic architecture"), to Mr. David A. Crane, to members of the Philadelphia Bicentennial International Exposition Planning Group, and to the Philadelphia Citizens' Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community, and all their advisors.

This brings to mind a curious footnote within Charles Jencks' The Story of Post-Modernism (2011):

Tom Wolfe lampooned architects' inability to reach the exuberance of Las Vegas sign artists, or 'Electrographic Architecture', in many articles. One key essay, republished in his collection Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1965, was written in his neo-hysterical style--'Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas!!!' Tim Vreeland has told me that when Venturi and Scott Brown were visiting Albuquerque circa 1968, he put a copy of Wolfe's book on the bedside table, and the couple were so impressed they drove off to see Las Vegas the next day. Their own shift in taste-culture towards commercial vernacular and Route 66, culminated first in an article, 'A Significance for A&P Parking Lots' (1968) and then the whole argument, Learning from Las Vegas, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA/London), 1972. Thus the Las Vegas polemic may date from Wolfe's humorous assault on professional taste, and that he too was to carry on with another attack on Minimalist Modernism, From Bauhaus to Our House, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1981. Reyner Banham took the Las Vegas sign artists in another direction, towards the dematerialized city of electronics, light, and environmental control. His The Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment, Architectural Press (London), 1969, inverts the Corbusian definition of architecture--'pure forms seen in sunlight'--to 'coloured light seen in impure forms'.

To clear up some of the chronology suggested above:

1965: On her way to California to teach in the School of Environmental Design at Berkeley for the spring semester, Scott Brown stops off in Las Vegas. That summer she travels in the southwest [including Albuquerque?]. In September, Scott Brown moves to Los Angeles and accepts the position of co-chair of the Urban Design Program at UCLA, where she remains through 1967. She recruits Venturi to act as a visiting critic.

1966: Scott Brown invites Venturi to visit Las Vegas with her for a four-day trip. In November the two travel the Las Vegas strip, from casino to casino, being alternately "appalled and fascinated" by what they see. ["Next I was taken to Las Vegas in 1966 by Denise Scott Brown--prepared a little by Tom Wolfe and a lot by Baroque Rome. Out of that trip came our studio at Yale and then our book Learning from Las Vegas."]

Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture is published by the Museum of Modern Art as the first in an intended series of occasional papers addressing issues of architecture and design (actual distribution is not until March 1967).

I doubt very much I'll actually see Open Air in person, but I could easily make a virtual model of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway Celebration for 1976. Or better yet, I should start publishing my ideas for the Semiquincentennial!

| |

2012.09.02 13:32

a whole bunch of...

Here's what I've found relative to 'electromagnetic architecture' at Quondam:

Re: E-M~A ARCHITECTURE

1999.03.19 14:37

...osmosis is "equalize the concentrations on either side of the membrane." This speaks directly, if you will, to inside and outside and the melding/meshing of the two [or more]. Osmotic architecture starts from there.

The kidneys are the second most osmotic organ within our body.

The lungs are the foremost osmotic organ within our body.

The heart is the foremost electromagnetic organ within our body.

Corporally (biologically), our electricity comes from salt (an electrified atom in our blood stream), and the iron in our blood (iron spontaneously magnetizes) supplies our magnetism. The S-A node of the heart concentrates the salt/electricity within the blood and this concentration then creates the electric 'spark' that intensifies the magnetism within the blood's iron, and thus the heart beats/pumps. The human heart is probably this highest order of 'machine' on this planet because what it pumps is what makes it pump -- the utmost in efficiency and sustainability.

Is electromagnetic architecture then that which continually strives toward becoming an architecture where what it facilitates is also what makes it a facilitator?

Is electromagnetic architecture that architecture which strives toward being the most efficient and sustainable?

Electromagnetic radiation is the definition of light. (Light, as far as science can presently tell, is an electromagnetic duality.)

Electromagnetic architecture in its purest sense is [also] an architecture of light.

...the relationship between electromagnetic architecture and osmotic architecture... ...our heart is surrounded by the lungs--electomagnetism surrounded by osmosis.

I do not see the body as a metaphor for architecture, rather I see the physiological operations of our body--metabolism, assimilation, fertility, osmosis, electromagnetism, etc.--as also being the imaginative operations of our mind.

I do not believe in a separation between the body and the mind. As our assimilating sciences increasingly tell us, we are what our DNA/body makes us. I simply see the way that DNA informs our body how to assimilate, metabolize, osmosify, electromagnify, etc., as being the same way our DNA informs our mind to assimilate, metabolize, osmosify, electromagnify, etc.

Architecture then can well be seen as a product of our respective assimilating, metabolizing, osmosifying, electro-magnetizing (etc.) imaginations.

I see very little need for humanity to look beyond itself in order to explain itself and how it operates.

and

Re: Osmosis /Electromagnatism /(An)Architecture

2000.03.28

The definition of osmosis you supplied is indeed the first definition of osmosis, but there are several others:

a process of absorption, interaction, or diffusion suggestive of the flow of osmotic action: as an interaction or interchange (as of cultural groups of traits) by mutual penetration esp. through a separating medium : a usually effortless often unconscious absorption or assimilation (as of ideas or influences) by seemingly general permeation

These subsequent definitions of osmosis relate rather well to architecture, as I've already mentioned, particularly to the architectural notions of transition from outside to inside and vice versa. I see the Pantheon in Rome and Kahn's Kimbell Art Museum as extremely fine examples of osmotic architecture. Furthermore, the Pantheon and the Kimbell are also extremely fine examples of electromagnetic architecture because they are both consummate examples of an architecture of light (i.e., electromagnetic radiation).

I am not here proposing that the above interpretations are the only correct interpretations of these buildings and the definitions under discussion, but I'm rather making connections between corporal physiological processes and architectures that for the most part haven't been made before.

tammuz, if you had said that the Ka'ba acts as the heart of Islam, then, yes, the Ka'ba presents an electromagnetic architecture. This doesn't really change, however, the perennial event of which the Ka'ba is the center presenting a 'conceptual wholeness'.

Also, the fact that you're the one changing the words I use, makes your system more tropic.

|