2012.07.11 13:33

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

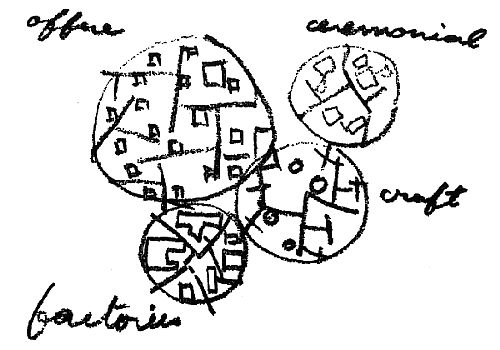

Alison Smithson, Patterns of association - Each district with a different function, 1953.

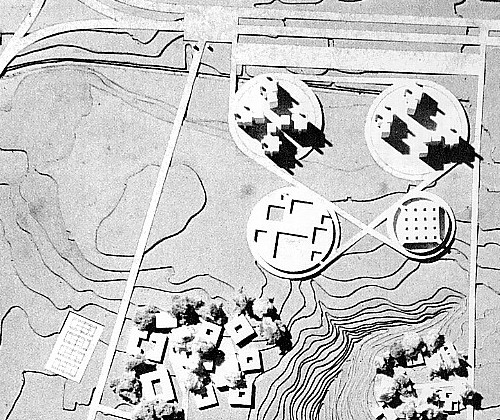

Louis I. Kahn, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, first design phase, 1959-60.

OMA, Penang Tropical City, 2004.

Patterns of association, indeed.

| |

2012.07.10 20:52

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

In an October 1969 ("The Big Little Magazine: Perspecta 12 and the future of the architectural past," Architectural Forum) review of Perspecta 12, Peter Eisenman writes:

"It is difficult to judge in retrospect whether Perspecta, while purporting to be a reflection of history, was not in itself creating history. And while the making of history cannot, of course, be directly ascribed to Perspecta, one can practically trace the history of post-war American architecture through its pages, from the appearance of Paul Rudolph's early Florida houses in Perspecta 1, to the Adler and DeVore houses of Louis Kahn in Perspecta 3, which in a quiet way signaled a significant, if marginal, change in the course of the Modern Movement--the eclipse of the free plan and a return to a direct modulation of space through structure."

Eisenman continues:

"There has unfortunately flourished, since the war, around the Modern Movement, a body of secondary literature which has tended not only to obscure some of the original ideas adherent to this movement, but also in some cases, in a search for an over-simplified version of history (and because of highly simplistic criteria of explanation), created an idealized picture of it--which can hardly be regarded as a representation of reality. Thus, Kenneth Frampton's article on Pierre Chareau's Maison de Verre, both in its style of presentation and its choice of material, can be seen as a break from this tradition. And while such a documentation of this building, as well as other canonical works of the Modern Movement, is long overdue as a contribution to the history of the recent past, it is the quality and scope of the documentation which commands our attention. Here is a set of precise, hard-line drawings, restrained, elegant, almost in the genre of the building itself, which certainly must establish a standard for such a presentation. But further, it is the abstract style of drawing in itself, the emphasis on plan, section, and axonometric view, which makes them useful for an analytical approach to the building. It is important to note that it was Frampton who had these drawings made in this particular manner; first because they probably did not exist, and second, because they present the building and the ideas inherent in it in a way that is not possible to retain, even when one is confronted with the actual fact."

Thirty-five years later Eisenman publishes Ten Canonical Buildings 1950-2000 (2008), where Louis I. Kahn's Adler and DeVore Houses are featured (which actually makes for a total of eleven canonical buildings within the book, but who's counting). Regarding the Adler and DeVore Houses:

"In the Adler and DeVore Houses of 1954-55, unlike in many of his other projects, Kahn achieves what could be considered an architectural text in diachronic space. This is brought about by the superposition of classical and modern space; that neither of these "times" dominates results in a dislocation of moments or, in other terms, a disjunction that is experienced in space. In the Adler and DeVore Houses, Kahn presents architecture both as a complex object and as the potential for the subject to experience the object as both a real space and an imaginary space. Both conditions are present and can be read, each in turn displacing the other. It is this unresolved moment in the Adler and DeVore Houses, which are themselves suspended in real time between the Trenton Bathhouse and the Richards Medical Center, that makes these two houses different from much of Kahn's other work. It is in the context of the denial of axial symmetries and part-to-whole relationships evident in much of Kahn's later work that these differences lie.

Thus the Adler and DeVore Houses can be seen to articulate an alternate internal logic: first, as a conscious, didactic proposal against the free plan of modern architecture, and second, as a critique of modern architecture."

To be precise, the Adler and DeVore Houses (1954-55) predate the Trenton Jewish Community Center Bathhouse (1956-57).

Eisenman continues:

"The hipped roofs of Kahn's Trenton Bathhouse, as well as its emphatic materiality, are clearly antecedents to the Adler and DeVore Houses, given that initial sketches of both houses similarly have hipped roofs. The Trenton Bathhouse is the first example in America of a massive brick and concrete structure denying the free plan and dynamic asymmetries of modernism with a classicizing nine-square plan. While only a small portion of the Trenton Bathhouse was built..."

Again, it is in fact the early hipped roofs schemes of the Adler and DeVore Houses that are antecedents to the Trenton Bathhouse, and, as built, the Trenton Bathhouse is complete. Eisenman confuses the Trenton Jewish Community Center Bathhouse with the much larger Trenton Jewish Community Center Community Building which was a wholly separate building design never executed.

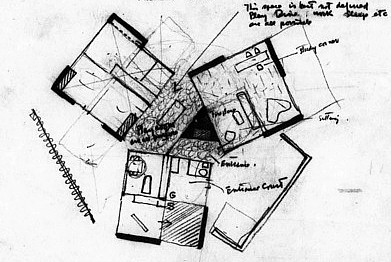

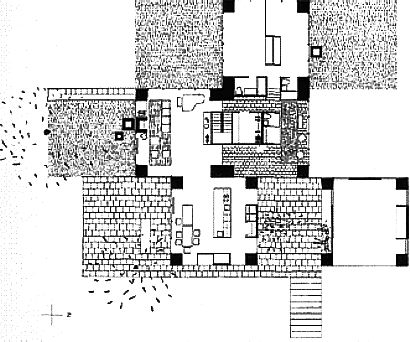

When seen in (correct) chronological order and at the same scale, a number of Kahn designs, centering on the Adler and DeVore Houses, reveal a more interesting evolutionary development of the "eclipse of the free plan and a return to a direct modulation of space through structure."

Fruchter House 1952-53 (not to scale)

Adler House 1954-55

DeVore House 1954-55

Trenton Jewish Community Center Bathhouse 1956-57

Trenton Jewish Community Center Day Care 1957

Goldenberg House 1959

Fisher House 1960-67

| |

2012.07.07 12:23

Why are the vast majority of architects liberal?

A big part of Hilter's "plan" was to "unite" all ethnic "Germans" living throughout (mostly eastern) Europe. Both my parents were ethnically German, yet neither of them was born within German borders--my father was born in a very small 'German' village in Poland (and thus nationalistically Polish), and my mother was born in a small 'German' town in what was in 1924 Serbia (and thus nationalistically Serbian, although my mother's mother, born in the same place as my mother, was in 1902 born within the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Largely due to the Austro-Hungarian Empire there was a quite substantial population of Ausland Deutsche (ethnic Germans outside the German land) throughout eastern Europe, Romania, even as far east as Ukraine, and Hitler pretty much accomplished his goal of gaining control of the Ausland Deutsche and the land where they lived, and, because of their ethnicity, all Ausland Deutsche, including both my parents and their respective families, were officially declared German citizens (and even to this day the German government considers all Ausland Deutsche that were declared German citizens under the Third Reich to still be German citizens).

The WWII aftermath of many Ausland Deutsche is indeed tragic. With the Soviet takeover of eastern Europe, the relatively new German citizens still there were almost immediately put into Soviet concentration camps. I personally have not-too-distant relatives buried in mass graves in what is today again Serbia, and both my parents spent five years (very beginning of 1945 to very end of 1949) in labor concentration camps in southern Ukraine, my father first a coal miner then construction worker and my mother a coal miner the whole five years--in September 1945 my father was 22 years old and in May 1945 my mother was 21 years old. It was indeed within this concentration camp within Ukraine that my parents first met.

The point of this here, within the context of several comments above, is that there are even substantial numbers of Germans that became victims of the extreme aggressive policies of Hitler's Third Reich.

2012.07.06 12:19

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized

"This would be all right if the architect were simply a servant. Perhaps he is. But during the past generation he has given himself airs as a social engineer, a man of high ideals and touchy honor. If so, it is probably time for him to draw the stub of whatever remains to him now. Perhaps he will get on the other side of the table himself, as Barnett, Stern, Robertson, and others have done in New York and elsewhere, since the most challenging and rewarding projects of the future, such as proper mass housing and so on, will be handled there, and real professional competence must be available lest all be lost. To save his soul he may take up Advocacy Planning of the kind organized through the Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem (ARCH) by Richard hatch, since succeeded by Max Bond, as the black community moves toward the control of its own neighborhoods. Perhaps the architect will organize in other ways outside the agencies, reshaping the American Institute of Architects to act as a true urban force as he himself slowly grows into an understanding of what such forces are. In that connection, it will be interesting to see if the A.I.A. will attempt to defend the commendable design by Romaldo Giurgola for its own projected building in Washington, to which it gave a prize in an honest competition, and to which Washington's Fine Arts Commission has since denied a building permit. "You will thank us someday, Mr. Giurgola," one of the more unlikely members of that commission was heard to say. (As this book went to press, in late 1968, Giurgola had been forced to return some half-dozen times with changes required by the Commission's undeniably offensive and certainly narrow-minded dominant architectural member. Finally, after having injured his light and buoyant design considerably in order to conform to the Commission's ponderously classicizing taste, Giurgola was forced by his professional integrity to resign the commission. The A.I.A. backed him not at all. Again, Robert Venturi's design for the Transportation Square Office Building, also a competition winner and already approved by the Washington Redevelopment Authority, was denied a permit in a hearing that was conducted at such a low level of personal and professional abuse that the Commission refused to release its transcript."

--Vincent Scully, American Architecture and Urbanism (1969), pp. 227-9.

The "Commission's undeniably offensive and certainly narrow-minded dominant architectural member" was Gordon Bunshaft--Bunshaft was a member of The Commission of Fine Arts, Washington D.C. from 1963 to 1972.

For excerpts of the Transportation Square Office Building meeting ‘transcript' see pages 140-1 of the first edition of Learning from Las Vegas. Here we learn that "the Washington Fine Arts Commission rejected it as "ugly and ordinary."" But my favorite quotation comes from the Chairman, John Walton: "Will that woman [no doubt Denise Scott Brown] be quiet. I know how to run my own meetings."

The Philadelphia School, deterritorialized will often investigate the (early) relationship between Giurgola architecture and Venturi architecture, as well as their respective relationships with Kahn architecture. One of the last episodes between Giurgola and Venturi occurred at the very beginnings of Roma Interrotta. When each of the invited architects received their section of the Nolli map of Rome, they also got to see what sections the other invited architects received. The Venturi office preferred the section received by the Giurgola office, so the Venturi office asked the Giurgola office if they wouldn't mind exchanging sections. The Giurgola office said they'd be happy to exchange, but they would rather ask the Roma Interrotta people before doing so. The Roma Interrotta people said the exchange was OK, and the rest is architectural history.

|