28 December 1778 Monday

. . . . . .

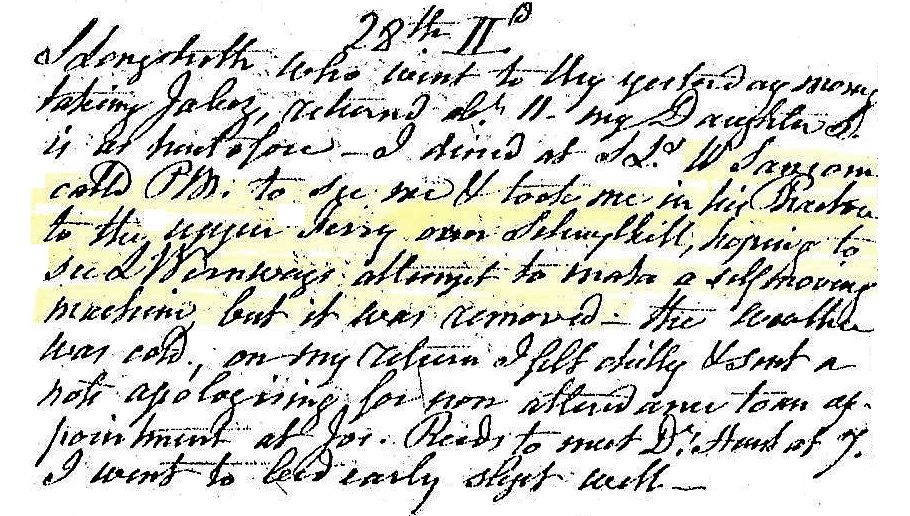

28 December 1812 Monday

S. Longstreth who went to Ury yesterday morning taking Jabez, returned about 11. My daughter S. is as heretofore. I dined at SL's. W. Sansom called PM to see me and took me in his [?] to the upper ferry over Schuylkill, hoping to see L. Wernway's[?] attempt to make a self moving machine, but it was removed. The weather was cold. On my return I felt chilly and sent a note apologizing for non attendance to an appointment at Jos. Reeds to meet Dr. Hunt at 7. I went to bed early, slept well.

28 December 1997

R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

p. 282:

How, or on what conditions, can the historian know the past? In considering this question, the first point to notice is that the past is never a given fact which he can apprehend empirically by perception. Ex Hypothesi, the historian is not an eyewitness of the facts he desires to know. Nor does the historian fancy that he is; he knows quite well that his only possible knowledge of the past is mediate or inferential or indirect, never empirical. The second point is that this mediation cannot be effected by testimony. The historian does not know the past by simply believing a witness who saw the events in question and has left his evidence on record. That kind of mediation would give at most not knowledge but belief, and very ill-founded and improbable belief. And the historian, once more, knows very well that this is not the way in which he proceeds; he is aware that what he does to his so-called authorities is not to believe them but to criticize them. If then the historian has no direct or empirical knowledge of them, what kind of knowledge has he: in other words, what must the historian do in order that he may know them?

p. 282-3:

In a general way, the meaning of the conception is easily understood. When a man thinks historically, he has before him certain documents or relics of the past. His business is to discover what the past was which has left these relics behind it. For example, the relics are certain written words; and in that case he has to discover what the person who wrote those words meant by them. This means discovering the thought (in the widest sense of that word: we shall look into its preciser meaning in sec. 5) which he expressed by them. To discover what his thought was, the historian must think it again for himself.

[I could paraphrase this entire paragraph in terms of drawings versus written words.]

p. 283:

Suppose, for example, he is reading the Theodosian Code, and has before him a certain edict of an emperor. Merely reading the words and being able to translate them does not amount to knowing their historical significance. In order to do that he must envision the situation with which the emperor was trying to deal, and he must envision it as that emperor envisioned it. Then he must see for himself, just as if the emperor's situation was his own, how such a situation might be dealt with; he must see the possible alternatives, and the reasons for choosing one rather than another; and thus he must go through the process which the emperor went through in deciding on this particular course. Thus he is re-enacting in his own mind the experience of the emperor; and only in so far as he does this has he any historical knowledge, as distinct from a merely philosophical knowledge, of the meaning of the edict.

[This explains my process once I started to "read" the plan (after I achieved a critical mass of drawing). Moreover, it describes what I'm doing now in terms of "archeological" research.]

p: 283: (the steps of the re-enactment process)

Or again, suppose he is reading a passage of an ancient philosopher. Once more, he must know the language in a philosophical sense and be able to construe; but by doing that he has not yet understood the passage as an historian of philosophy must understand it. In order to do that, he must see what the philosophical problem was, of which his author is here stating his solution. He must think that problem out for himself, see what possible solutions of it might be offered, and see why this particular philosopher chose that solution instead of another. This means re-thinking for himself the thought of his author, and nothing short of that will make him the historian of that author's philosophy.

p. 283:

Such as objector might begin by saying that the whole conception is ambiguous. It implies either too little or too much. To re-enact an experience or re-think a thought, he might argue, may mean either of two things. Either it means enacting an experience or performing an act of thought resembling the first, or it means enacting an experience or performing an act of thought literally identical with the first. But no one experience can be literally identical with another, therefore presumably the relation intended is one of resemblance only. But in that case the doctrine that we know the past by re-enacting it is only a version of the familiar and discredited copy-theory of knowledge, which vainly professes to explain how a thing (in this case an experience or act of thought) is known by saying that the knower has a copy of it in his mind. And in the second place, suppose it granted that an experience could be identically repeated, the result would only be an immediate identity between the historian and the person he was trying to understand, so far as that experience was concerned. The object (in this case the past) would be simply incorporated in the subject (in this case the present, the historian's own thought); and instead of answering the question how the past is known we should be maintaining that the past is not known, but only the present. And, it may be asked, has not Croce himself admitted this with his doctrine of the contemporaneity of history?

[I could paraphrase this whole paragraph to explain my personal experience in the redrawing process. It also relates to the subtitle of my proposed book. I should become familiar with Croce.]

p. 289:

We now pass to the second objection. It will be said: "Has not this argument proved too much? It has shown that an act of thought can be not only performed at an instant but sustained over a lapse of time; not only sustained, but revived; not only revived in the experience of the same mind but (on pain of solipsism) re-enacted in another's. But this does not prove the possibility of history. For that, we must be able not only to re-enact another's thought but also to know that the thought we are enacting is his. But so far as we re-enact it, it becomes our own; it is merely as our own as we perform it and are aware of it in the performance; it has become subjective, but for that very reason it has ceased to be objective; become present and ceased to be past. This indeed is just what Oakeshott has explicitly maintained in his doctrine that the historian only arranges sub specie praeteritorum what is in reality his own present experience, and what Croce in effect admits when he says that all history is contemporary history.

[It will be helpful to bring up this second argument in relation to my own "reenactment." It also relate to the new presence of the Campo Marzio due to my redrawing of the Ichnographia in an entirely new medium.]

p. 300:

To disengage ourselves from these two complementary errors, we must attack the false dilemma from which they both spring. That dilemma rests on the disjunction that thought is either pure immediacy, in which case it is inextricably involved in the flow of consciousness, or pure mediation, in which case it is utterly detached from that flow. Actually it is both immediacy and mediation. Every act of thought, as it actually happens, happens in a context out of which it arises and in which it lives, like any other experience, as an organic part of the thinker's life. Its relations with its context are not those of an item in a collection, but those of a special function in the total activity of an organism. So far, not only is the doctrine of the so-called idealist correct, but even that of the pragmatists who have developed that side of it to an extreme. But an act of thought, in addition to actually happening, is capable of sustaining itself and being revived or repeated without loss of its identity. So far, those who have opposed the 'idealists' are in the right, when they maintain that what we think is not altered by alterations of the context in which we think it. But it cannot repeat itself in vacuo, as the disembodied ghost of a past experience. However often it happens, it must always happen in some context, and the new context must be just as appropriate to it as the old. Thus, the mere fact that someone has expressed his thoughts in writing, and that we possess his works, does not enable us to understand his thoughts. In order that we may be able to do so, we must come to the reading of them prepared with an experience sufficiently like his own to make those thoughts organic to it.

axes of life and death

As I was reading Dripp's The First House, p. 62, about the Roman cardo & decumanus, I began to wonder whether the life and death axes of the Campo Marzio are also a reënactment of the ancient town planning axes. Upon inspection of the Ichnographia, I found that the life and death axes are just a few degrees shy of being on the true cardinal points. Moreover, the cardo, the north-south axis corresponds to the axis of death in the Ichnographia, and traditionally "refers to the axis around which the universe rotates." The Campo Marzio axis of life, the east-west axis, the decumanus, refers to the rising and setting of the sun. There is now much to think about with regard to further meaning of Piranesi's axes, especially within the overriding history and tradition of Roman city planning.

I can already begin to speculate where the axis of life, which is the longest axis in the Ichnographia is purposefully disguised because, as the decumanus, it should be secondary to the cardo--in this case, the axis of life. Is Piranesi again playing with inversion? I also wonder if Rykwert has anything to say with regard to the apparent lack of a cardo and decumanus in ancient Rome's city plan.

Today it also dawned on me that the Arch of Theodosius et al is placed at the tip of the axis of death. In its smallness (and apparent insignificance) it reminds me of the tiny unnamed intercourse building at the tip of the axis of life. What is of utmost significance, however, is that this particular Triumphal Arch is indeed the last (latest) building addition within the Ichnographia, and dates from anywhere between AD 367-395. There is no building within the Ichnographia that is named for a later Emperor [sic].

The placement of this arch at the tip of the axis of death is very symbolic in that it represents the very end--Theodosius was the last Emperor to rule over both the East and West Empire and it was he who instituted Christianity as the state religion--the end of the pagan empire and the end of any semblance of a totally unified empire. Thus, the intercourse building at the tip of the axis of life represents the very beginning (of life and quite possibly of the Ichnographia's plan formations, as well) and the Arch of Theodosius et al at the tip of the axis of death represents not only Rome's end as the sole capital of the civilized world, but also its end as capital of the pagan world.

It is through his plan of the city of Rome that Piranesi writes (and/or rights) the history of Rome itself. Through the Ichnographia Piranesi reënacts the history of the city.

This new information adds tremendously to the meaning of the life and death axes, and the overall symbolism or meaning of the plan as well. That Piranesi carefully focused on the inversion of Rome from ultimate pagan world capital to a Christian and only partial world capital falling into lesser and lesser significance is now completely obvious. In this sense, the Ichnographia represents Rome at its pagan zenith (acme, peak, summit), and it is metaphorically downhill from this point for Rome does not reach its zenith as "Christian world capital" until the Renaissance--Rome's rebirth.

The literary reference to the Arch of Gratian, Valentinian (II) and Theodosius (in the Campo Marzio text) is Dalle Rovine, e dall'incrizione, che secondo la tradizione del Marlini, e nel Nardini nel lib. 6, al cap 6.>> Si reportano nel cap. 6, art. 18.

Here is also an interesting citing from Encyclopedia Britannica 19-459d (Jocelyn Mary Catherine Toynbee):

"The last examples of Roman carving are the reliefs on the base of the obelisk of Theodosius in the Hippodrome at Constantinople, where the emperor and members of his court, ranged in rigid hieratic poses, watch the shows."

More from Encyclopedia Britannica 19-541b (Edward Arthur Thompson):

"After the death of Theodosius I in 395 the empire was never again ruled for any significant length of time by a single emperor. From 395 to 480 it was ruled by two or more colleagues, one in the east or one or more in the west, all with equal rights."

28 December 2013

It has always been my impression that Piranesi's Scenographia of the Campo Marzio is a perspicacious demonstration of how little actually remains of the ancient Roman architecture that once stood within the Campus Martius.

The Scenographia depiction of the 40 existent in situ architectural remains of the Campo Marzio is in stark contrast to the Catalogo list of 322 buildings mentioned by ancient authors to have once existed within the Campo Marzio.

28 December 2022 Wednesday

Today is Horace Trumbauer's 154th birthday, and last night BO texted a link to Lynnewood Hall...

"Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf of Sweden (a.k.a. Gustavus Adolphus, later King Gustaf VI Adolf), and his consort, Princess Louise Alexandra ... arrived in Philadelphia on the afternoon on June 1, [1926]. Their destination was Whitemarsh Hall, the magnificent 300-acre suburban estate of banker Edward T. Stotesbury. Stotesbury, senior partner of Drexel & Company, was reputed to be Philadelphia’s wealthiest man. He and his wife Lucretia (known as “Eva”) were in charge of hospitality for the Sesqui’s most distinguished guests. Whitemarsh Hall was a 147-room, six-floor mansion designed by Horace Trumbauer in the Georgian style, surrounded by formal gardens and fountains."

Thomas H. Keels, "When The Swedes Saved The Sesqui (Sort of)" (2017).

Remember when I told you about the Crawford sisters fabricating the story of Gustav V, King of Sweden, staying at Ury in 1926?

|