The via Flaminia, leading to Ariminum, was built by C. Flaminius, consul in 223 B.C. It began at the porta Fontinalis and ran north by east through the porta Flaminia. The first part of this road, from the Capitol to the porticus Agrippae, was called the via Lata, and corresponded with the modern Corso. The ancient pavement has been found both within and without the wall. (Platner)

Vincenzo Fasolo, "The Campo Marzio of G. B. Piranesi".

2691a

1956

book on the Campo Marzio

1995.01.03

... the Via Flaminia, the only street (as far as I can tell) that is named in the plan. I think I somewhere read that Piranesi was trying to correct what he thought was a mistaken idea of where the Via Flaminia actually was. Besides the Historical connection, the street in the plan offers an interesting typological collection of plebeian houses with the occasional sprinkling of monuments and monumental buildings. An analysis of the street might disclose an interesting urban design prototype.

Redrawing History - archeological accuracy

1997.08.16

...the Via Flamina and its odd placement in the Campo Marzio. Fasolo refers to the placement of the Via Flaminia as arbitrary. This then also brings into question the positioning of the Equiria, (which Fasolo wrongly identified as a waterway) and how the Via Flaminia today is actually the route inscribed by the Equiria of the Campo Marzio, and how the present day Corso, whose name refers to the ancient race course (I still have to verify this) is not depicted within Piranesi's Campo Marzio but the "arbitrary" Via Flaminia seems to take its place as the "main street" of the redrawing.

...note the locations in the Campo Marzio where Piranesi actually did excavation--this information is available in Lanciani's Forma Urbis Romae.

There is also the connection between the big scoop on the bank of the Tiber (depicted on the Nolli plan) and the Natatio (beach) at the same location in the Campo Marzio.

...a comparison between the Minerva Medica and the Horti Luciliani. Piranesi may be, at times, loose with what he puts where and what the buildings look like, but he is consistent in terms of finding his inspiration in actual Roman buildings.

| |

life, death, and the triumphal way [inversion]

1998.01.11

I spoke with Sue Dixon yesterday and told her of my latest "discoveries" regarding the life and death axes of the Ichnographia, the arch of Theodosius et al and the further symbolism of the Porticus Neronianae as an inverted basilica-cross. She too became excited by my discoveries and then also brought further insight, especially in reference to the issue of the papacy and its research during the eighteenth century into the early Christian Church. She spoke of Bianchini and his nephew (a contemporary of Piranesi's) and their dual volumes of pagan (Roman) and Christian art, and she also mentioned how the papacy of the eighteenth century had lost (more or less by force and financial restraints) much of its political power and thus took on a very pious role--exhibiting not its worldly power but its almost mystical or spiritual power.

What I was saying about the apparent Pagan-Christian conversion-inversion narrative of the Ichnographia fit with what research Sue is continually doing regarding the contemporary and early eighteenth century influences on Piranesi and the whole issue of proto-archeology - history of the eighteenth century.

After speaking with Sue, I began thinking of the significance of the arch to the victory over Judea that is situated to the western end of the Bustum Hadriani. I now see it related to the pagan-Christian conversion-inversion of Rome, but in terms of Roman history it is a somewhat marginal issue-event. Yet, in terms of Christianity, the Roman victory over Judea, and hence the fall of Jerusalem, is a significant, albeit still sorrowful, event because of this event's relationship, and indeed verification of certain-particular passages of New Testament Scripture, i.e., Jesus' answering the Apostles question of when Jerusalem would end (which I think is in Mark or the Acts of the Apostles). Seeing how a seemingly minor event in Roman (Imperial) history can at the same time be a critical event for the foundation of Christianity made me think about how the Roman Judaic victory unwittingly gave manifest confirmation that Christianity had from that point forward absorbed Judaism.

Although it comes from the margin or edge, the significance of the victory of Judea arch sheds a major light upon the narrative Piranesi tells--Piranesi's "story" is about Christianity's similar absorption and concomitant destruction of paganism. This notion of Christianity absorbing both Judaism and paganism has major theological implications, especially with regard to a heretofore perhaps ignored importance-significance of Rome and the Roman Empire within the Canon and doctrine of the Christian (Catholic) faith.

...the real axis of St. Peter's Basilica and Square. This axis is fundamental to Piranesi' axis of life--and the most significant point alone the existing axis is the burial place of St. Peter, which, although not noted in the Ichnographia, is nonetheless an ancient Roman artifact.

...the story of the Triumphal Way. ...follow the triumphal path on the plan, and explain the entire route in Roman-pagan-triumphal ritual terms. ...bring up the essential concept of reenactment, the reenactment that Piranesi here designed, especially the well planned sequence of stadia and theaters along the way. Piranesi made use of what was actually once there.

When the route reaches the wall at the Temple of Janus, attention turns to Triumphal Arch-Gate, which is closed during the years of inactivity. Does the Triumphal Way then bounce off the wall and go back the way it came? Does the Temple of Janus allow us to go in either direction? (Other clues of inversion abound: obelisk in the Horti Salustiani, Porticus Phillippi, the Arches along the Via Lata, the Via Flaminia, the Circus Flaminia, the obelisks at Augustus's Tomb. The recurring inversion theme points to a greater meaning/symbolism.) The Temple (arch) of Janus represents the Arch of Janus built by Constantine (who might himself be called the Janus figure of Christianity) and this is the initiation of the way of Christianity's triumph: the profane to the sacred; the forest, hell, purgatory, heaven; the path of salvation through Christ and the Church.)

...the way from the profane to the sacred ends at the Area-Templum Martis as symbolic of the union of the most sacred site ancient Rome (or at least its point of origin) with the most sacred site of Christian Rome (St. Peter's place of burial) and also the point of origin of Christian Rome.

The garden of Nero is the ultimate field of inversion: Horti Neroniani to Vatican City, the garden of antichrist to the Church as the Body of Christ, the foremost seat of the Church of Christ, and finally St. Peter's inverted crucifixion begins the conversion of Rome.

I will conclude the inversion from pagan to Christian story-line by returning to the axis of death and the Arch of Theodosius et al at its tip, and thus when compared with the intercourse building we have depicted the beginning and the end of pagan Rome. To this I will add the Jewish Victory monument and end with the notion that Piranesi has here used architectural plans and urban design to tell the "history" of ancient Rome, however, one has in a sense read both the "positive" and the "negative" image-plan -- a story where the first half is the reciprocal of the second half (and vice versa). (I am oddly reminded here of the double theaters story from Circle and Oval in St. Peter's Square.)

| |

Gaius Flaminius

1998.02.15

...researched Gaius Flaminius because Piranesi's inversion of the Circus Flaminius within the Ichnographia. It turns out that Flaminius did go against the grain of the Senate and was of plebeian background. Sue Dixon also mentioned that Piranesi uses Flaminius as a point of subdivision in his Il Campo Marzio text of the districts history, (Piranesi actually thinks highly of Flaminius and his circus), and she (Sue) noted how the via Flaminia is not correctly delineated within the Ichnographia--the circus and the road were built by the same man. Perhaps Piranesi chose to delineate both these entities incorrectly to accentuate that Flaminius, in going against the grain, began a new effect on the land use of the Campo Marzio--thus showing the circus rotated 90 degrees in order to make it stand out. As for the Via Flaminia, there is no immediate explanation as to why it meanders off into a totally wrong direction, but it is worth noting the many plebeian homes that Piranesi situates along the street; this may be a reference to Flaminius' own plebeian background.

There is also the area called Prata Flaminia (within which the Porticus Philippi is situated) and I'm not sure if Flaminius also donated this land to the city/citizens.

Bufalini--Nolli--Piranesi 02

2010.09.12

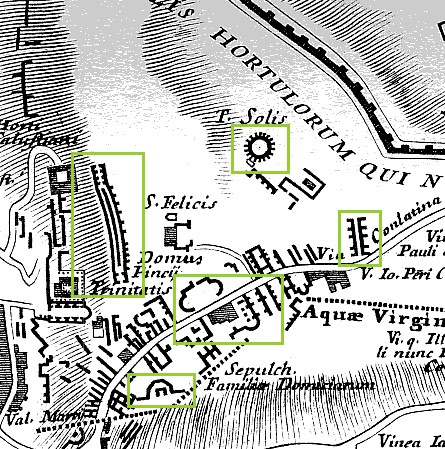

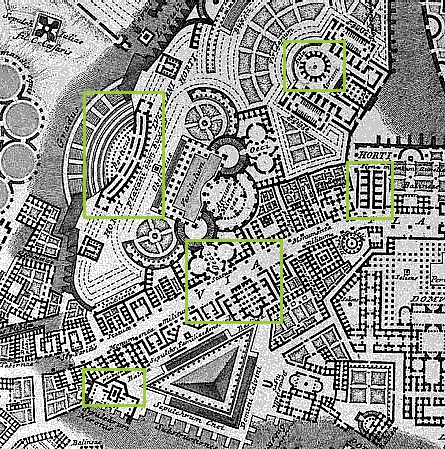

Piranesi acquired a detailed knowledge of Bufalini's Ichnographia Urbis of 1551 via his direct involvement with Nolli's Pianta Grande di Roma of 1748. A decade later, in 1758, Piranesi began his Ichnographia Campus Martius where, in some instances, he utilized Bufalini's map/plan as source material for the redrawing of ancient Rome's urban plan. Bufalini's plan, especially in the open areas all around the built-up section of Medieval and Renaissance Rome, includes 'reconstructions' of the larger ancient edifices like the imperial baths and stadiums, and some temple complexes. There are also near countless unnamed, fragmentary plans of ancient remains; remains, moreover, that, after consulting Nolli's plan, appear to no longer exist in Piranesi's time. It is from a select group of plan fragments on the Mons Pinicus or Collis Hortulorum of the Ichnographia Urbis that Piranesi imaginatively redraws the Horti Luciliani, the Sepulchrum Neronis, a Basilica along the Via Flaminia, the Horti Pincii, and the Monumentum Comitis Herculis.

Piranesi's resultant redrawn plans suggest a methodology whereby the fragmentary plans of Bufalini were used as kernels of ancient fact that, in turn, galvanized newly interpreted redrawings of what once was. As suggested by Dixon, "as there were great gaps in the knowledge of the past, great leaps were then needed to supply the holistic vision of the past which was the aim of scholars--archaeologists and historians--like Piranesi. In the Ichnographia, Piranesi filled the gaps..." Futhermore, from a strictly design point of view, Piranesi used some the fragmentary plans of Bufalini as contiguous elements which, when mirror-copied and multiplied, manifest the beginnings of the new plans.

Besides Bufalini's plan delineations, Piranesi also makes use of Bufalini's labelings. Bufalini labels all his full plan reconstructions of ancient buildings, often labels the fragmentary plans, and even labels blank locations (indicating the spot of an ancient edifice although actual remains no longer then existed). In utilizing the labels within the area of the Mons Pinicus or Collis Hortulorum, however, Piranesi hardly remains faithful to Bulafini's data. For example, where Bufalini positions the Horti Salustiani and Domus Pincii, Piranesi places the Horti Luciliani and, in turn, places the Horti Salustiani and Domus Pincii further east; the street Bufalini labels Via Conlatina, Piranesi labels Via Flamina; where Bufalini positions the Sepulcr. Neronis, Piranesi places the Bustum Caesaris Augusti and, in turn, labels an unnamed fragment along his Via Flaminia Sepulchrum Neronis; a small round structure Bufalini labels T. Solis, Piranesi labels Aula within the Horti Luciliani and, in turn, labels a newly imagined round building further south Delubrum Solis. It is honestly difficult to discern whether Piranesi is here playfully inverting Bufalini's data or actually rectifying Bufalini's "facts" with advanced knowledge of the past. Like Bufalini, Piranesi groups the Domus Martialis, Ludus Florae and the Templum Florae together, but he positions the group further west and moves the Domus Martialis south rather than north of the Ludus Florae. And where Bufalini locates the Sepulch. Falimiae Domiciarum, Piranesi places a very small Sepulcr. Familiae Aenobarb. and a very large Sep. Cnei Domitii Calvini whose plan Piranesi bases on an unrelated fragment of the Forma urbis.

|