Venturi also made some sprightly design jokes early in the permissive decade. For a house in Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania, he winked at the ordinary Cape Cod cottage and twisted a simple peaked-roof scheme around so the front door is in the gable end; then he made the gable end into a broken pediment that, perhaps pretentiously, recalls the great English mannerist historical houses he is so fond of. Inside, the most celebrated of his design jokes is a stair that leads to nowhere; it can be used as a large whatnot and as a ladder to aid in washing a window, but otherwise there is no function. It is, nevertheless, a gantry to the sky, an infinity stair that is a clear symbol of our age.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), p. 73.

Robert Venturi's Chestnut Hill house (1962) had already used a diagonal entry plan "to relate to directional space."

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), p. 102.

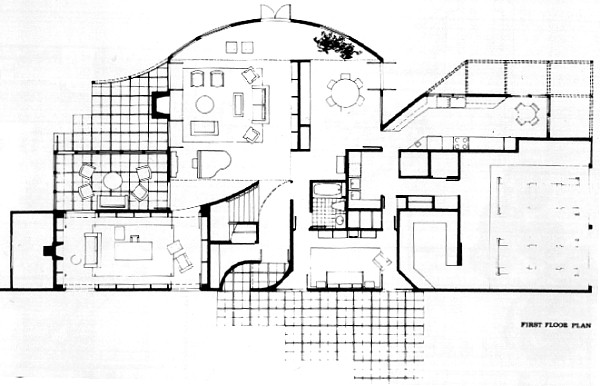

Robert Venturi's best-known permissively spontaneous work is the main stair of the Chestnut Hill house (1962). It runs between the fireplace and the front door and accommodates itself both to the fixed fireplace form on the one side and to the needs of the front door on the other side, for more generous width. Consequently, the stair ends up as a special "nonformalized" shape that was spontaneously induced by the conditions of its surroundings; its form is determined by the interstice between the two walls. In the same house, the rain leader that plunges haphazardly across the facade, does so, Venturi said, because "Life is like that," adding that there cannot be a single order to cover everything because there will always be something that won't fit.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), pp. 118-20.

Robert Venturi, discussing his firm's Chestnut Hill residence in Complexity and Contradiction, explained, "The main reason for the large scale is to counterbalance the complexity. Complexity in combination with small scale in small buildings means busyness. Like other organized complexities here, the big scale in the small building achieves tension rather than nervousness--one appropriate to such architecture.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), p. 233.

| |

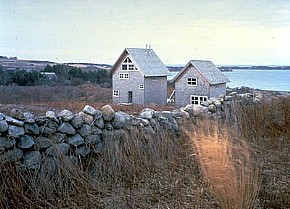

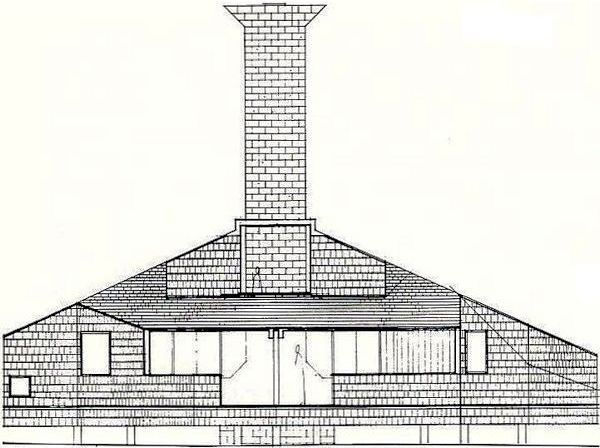

Few houses support so much discussion and analysis in their first decade as Robert Venturi's house (1962) in Chestnut Hill, outside Philadelphia [sic]. The house is a simple-looking building on a suburban lot. Its overall form is that of a gabled and chimneyed cottage, but Venturi has twisted it around in plan as we have seen and put the entrance on the gable side. That north elevation is reminiscent of a detail of Blenheim Palace--the attic of the principal courtyard portico--one of the mannerist works of Sir John Vanbrugh that Venturi is so fond of. Like a new broken pediment, the two side pavilions are extended toward the center in plan, like a detail of historical architecture blown up to make an entire building for our domestic decade. The exterior is otherwise austerely sited, striped of podium and landscaping, like Palladian villas in Italy and England. Then, whimsically, the Palladian hallmark, the arched window, is alluded to by a tacked-on broken arch in wood trim, which presages the half-vault ceiling of the dining room. These means are used both to make historical allusions and also to use them perversely, campily, ironically, sardonically.

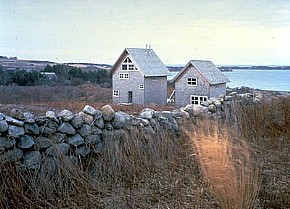

The front door, clearly situated at the center of the broken pediment, is nevertheless concealed, placed on the side with a diagonal "inflection" toward it, as Venturi says. Inside, the rectangular plan is spiked with diagonals, from the entry into other rooms and to the fireplace plan. Some of these angles are seemingly arbitrary, but lively and whimsical. The entry funnels one into the dining area, past the kitchen and past the adjacent stair to the second floor. The stair and kitchen walls are inflected like directional signals to lead occupants and to accommodate their movement. The house also rings variations on other supermannerist devises besides historical allusions and diagonals. The screen of walls, multilayered like three-dimensional facade architecture, can be seen in the front elevation, where they appear as superimposed on other screen that make up the elevations. And the painterly composition of the ordinary if irregular windows begin a direction that Venturi & Rauch developed more intricately in the Nantucket cottages fostered by the monumental explanations on historical analogy that the architect provided? Nevertheless, the historical analogy superimposes another scale of the mannerist age's ritualism into the personalized twentieth-century dollhouse. It is the superimposition of supermannerist superscale in one of its most intellectualized forms. Venturi as theorist traversed a complex argument of contradictory justification for the house that reflects more the wily inventiveness of his mind than the elaborateness of the house. And this can be said safely, since aestheticians recognize all design theory as ex post facto musing and rationalizing. Venturi explained the contradictions he expected everyone to find in the house. Its starkness elicited a cry that it was willful, ugly, and offensive. Its allusions and manipulations were greeted by others as cheerful, sprightly, fresh, and vital. Architecture critic Ellen Perry Berkeley said the house had "a serious whimsy, a rational ambiguity, a consistent distortion." We can add that it also has a studied chaos, a stark elaborateness, and a forced lightness.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), pp. 264-66.

| |

Cad collection 2182

2005.09.29 12:58

Modern crisp pitched roof

2005.10.12 17:46

Jimmy Venturi's new website...

...like, is it all conscious or sub-conscious, or osmotic even. I like it too because the 'artifacts', the designs, speak for themselves within a much larger architectural continuum.

...and seeing No. 9 again here made me think of the early Gehry three-in-a-row houses in Santa Monica(?), and then a lot of the "glass/wall boxy" houses designed now. And a couple of weeks ago the "pitched roof house" thread and seeing the Vanna Venturi House among the contemporary stuff also brought a perception to my eyes that wasn't there before.

I'll go for the continuum idea as to where architecture is really at.

2008.06.25 14:23

Can you say canonical?

"Eisenman's Canon..."

Luigi Moretti, Casa "Il Girasole," 1947-50

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, 1946-51

Le Corbusier, Palais des Congres-Strasbourg, 1962-64

Louis I. Kahn, Adler & DeVore Houses, 1954-55

Robert Venturi, Vanna Venturi House, 1959-64

James Stirling, Leicester Engineering Building, 1959-63

Aldo Rossi, Cemetery of San Cataldo, 1971-78

Rem Koolhaas, Jussieu Libraries, 1992-93

Daniel Libeskind, Jewish Museum, 1989-1999

Frank O. Gehry, Peter B. Lewis Building, 1997-2002

2008.06.25 20:31

Can you say canonical?

Just wait till you read the first few sentences on page 129. Apparently the book it interchangably tragic and comedic.

2011.01.28 10:26

7 Wonders (and a half) of POSTMODERN architecture?

Vanna Venturi House, 1959-64.

Piazza d'Italia, 1975-80.

Public Services Building (Portland), 1980-82.

AT+T Building, 1978-84.

seminal : highly original and influencing the development of future events

The Vanna Venturi House is the only seminal work within the above list. The rest are, at best, the apotheosis of Post-Modern architecture.

apotheosis : the ideal example; epitome; quintessence

Note the AT+T Building was complete a full 20 years after the Vanna Venturi House was complete. That's like relating a building completed today to a building completed in 1991!

| |

2011.11.05 14:57

Quondam's Fifteenth Anniversary

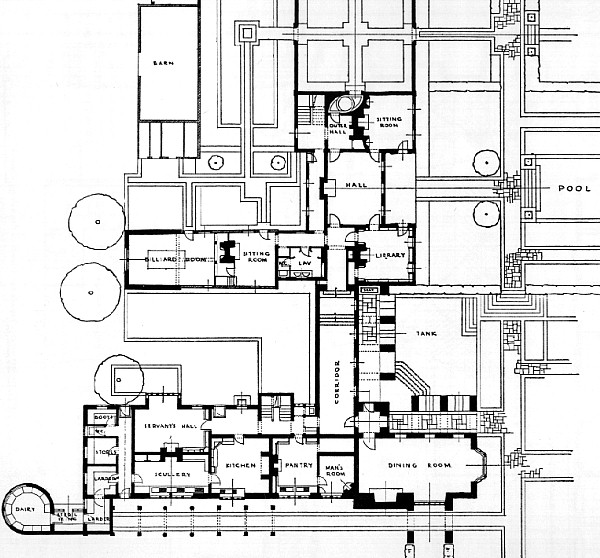

Great Maytham in Kent of 1910 is Queen Anne, but not the Queen Anne of the 1870s. Here a great mansion of the early eifhteenth century was re-created with such a plausibility of craftsmanship that after only half a century it was hard to believe it was not two hundred and fifty years old. A somewhat smaller house, the Salutation in Sandwich of 1912, is similar and perhaps even more remarkable as an example of what is almost 'productive archaeology' on the part of a man who was not, in fact, at all archaeologically minded. Such houses are the twentieth-century equivalents of Devey's in the nineteenth century, but they often have a witty originality in the handling of traditional detail that has aptly been called 'naughty' and is peculiarly personal to Lutyens.

Hitchcock, 1958

Robert Venturi, the most famous architectural thinker of his generation, was standing in the living room of his most famous house last week, making small talk with longtime Chestnut Hill friends, when in walked the most famous architectural thinker of the current generation, Rem Koolhaas.

In architectural terms, it was akin to the moment when Clinton met Kennedy, when Nabokov met Tolstoy, when Balanchine met Diaghilev. It was the young revolutionary meeting the old.

Koolhaas, 58, who became his profession's latest "starchitect" this spring with the opening of the new Prada boutique in New York's SoHo, was in Philadelphia to deliver a lecture. But first, the Dutch-born architect wanted to see the 1964 Chestnut Hill house that put Venturi on the map - and challenged the modernist hegemony. Venturi, 77, offered to conduct the tour of the home, now owned by the Hughes family.

It wasn't a complete clash of the generations, but it wasn't complete understanding, either. Venturi wore tweed. Koolhaas wore what looked suspiciously like Prada.

Venturi's little Chestnut Hill house, which is now considered a landmark of 20th-century architecture, seemed barely big enough to contain the lanky, 6-foot-6 Koolhaas, who strode into the house like a general and inspected the split staircase and the square, postmodern windows. Koolhaas spoke mainly with his eyebrows.

While radical in their day, those architectural features have now become so widespread that Venturi had to take pains to make sure Koolhaas knew how groundbreaking they once were.

"There are a lot of naughty things here," Venturi explained to his younger colleague as they walked outside to look at the chair rail that girds the exterior - a decorative touch that gave the modernist architectural establishment fits. "That took a lot of courage to do," added Venturi, who also challenged conventional thinking with his books, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture and Learning from Las Vegas.

Koolhaas, who was once compared to a motionless frog waiting to snap at a fly, assimilated Venturi's account with a barely perceptible purse of the lips.

"Did you feel it needed courage?" the Dutchman asked, after a moment.

Later, Koolhaas explained that he was a great admirer of Venturi and his partner, Denise Scott Brown. "Their interests were really revolutionary," he said. "It's baffling to me that they are treated with such skepticism."

Saffron, 2002.04.17

Yes, yes, yes to all the electronics, wall as sign, Dutch silences and possible revenge(s), but how is one to be really "naughty" these days?

Lauf, 2002.04.18

| |

2012.07.19

Cat's away, mice will play or Mom goes eclectic

|