It may not be coincidental that the villa at La Chaux-de-Fonds has as the principal motif of its main facade a flat white panel, divided into three--"the central one, elaborately framed, comprises an unrelieved blank white surface." Although the sources of Le Corbusier's panel are obviously different, the formal similarities to Venturi & Rauch's white brick billboard panels at the Guild House (1960-1965) and Fire Station No. 4 (1965) are unmistakable.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), p. 98.

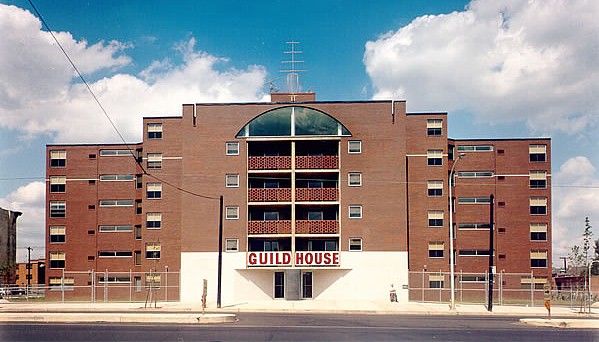

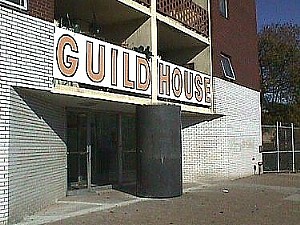

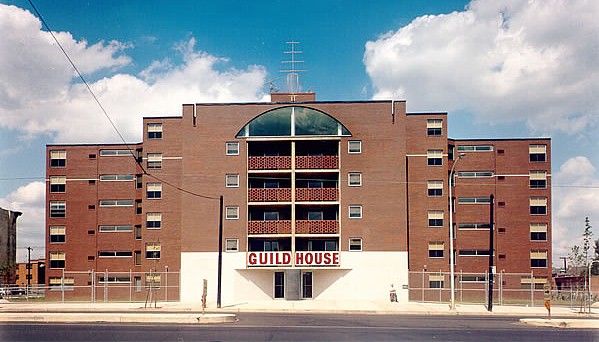

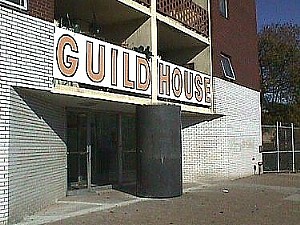

In the Guild House apartments for the elderly, built in Philadelphia (1960-1965), Venturi & Rauch first combined all the elements that later became the hallmarks of their design: The building adopts the idiom of the everyday, ordinary red brick apartment house--an acceptance of our pop reality and the neighboring buildings--and combines it with historical allusions. In plan and massing the structure resembles the entrance porticos of mannerist architecture. In the street-front facade, which is no higher than the rest of the roof line but which has two vertical slits like crenelations, the center portion has the effect of a parapeted screen of red brick atop a white brick base. This base, the main entry, is Venturi's first architectural billboard with oversized, purposely clumsy lettering on a white field. As another historical allusion, the entry reiterates becolumned porticos: whimsically, a single polished-granite column is placed in the middle, as if blocking a large entry, although the entry is actually composed of two small doors flanking the false, nonstructural cylinder; above, a series of balconies, topped by an arched window to a recreation room, suggests a monumental gateway to palatial residences of old. All the facades are sensitively composed by fenestration of different square and horizontal shapes, many of them oversize double-hung windows that recall the ordinary apartment house idiom. This attention to fenestration is a design activity of Venturi and Rauch's that reaches a culmination in the skillfully windows punched, like a key-punch card, in the firm's Mathematics Building for Yale (1970). As a final Pop art symbol of our age, "and of the aged who spend much of their time watching TV at the Guild House," as Venturi said, the first designed a nonfunctioning gold-anodized television antenna that is placed as the crowning heraldic emblem atop the arched ceremonial portal.

The effect of Guild House is unsettlingly ambivalent. It clearly presents a realistic acceptance of the everyday fact and occurrence of ordinary contemporary building, and this seems a straightforward, direct, and honest approach to our urban environment. Yet it also includes motifs of earlier, more monumental and pretentious architecture in an attempt to symbolize the residential pride of its elderly occupants; this is an intellectual overlay. What this blend of ordinary mediocrity and monumental pomp creates, therefore, is a singular and tensioned response.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), pp. 188-90.

In the vein of historical allusions, Robert Venturi's aesthetic theory is full of references to historical precedent from the beginning. His Pearson House project (1957) is said to have "domes"; the Duke House renovation (1959) is said to have "a Louis XIV scale in the Louis XVI building." His firm reiterated sixteenth and seventeenth screens in the design of the facades of the Guild House, Fire Station Number 4 in Columbus, Indiana, as has been mentioned, and they alluded to oriental moongates in the Varga-Brigio Medical Building

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), p. 262.

| |

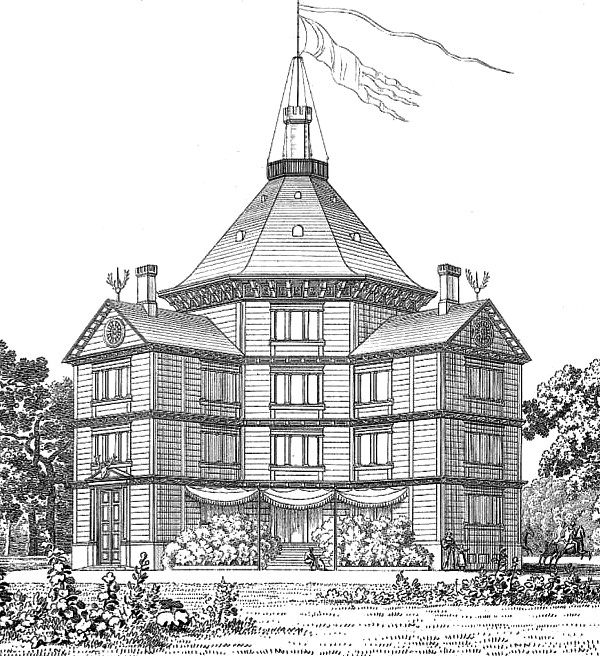

Venturi had compared the Guild House facade with the Château at Anêt.

C. Ray Smith, Supermannerism: New Attitudes in Post-Modern Architecture (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), p. 268.

1998.12.03 10:55

Re: CAD-CAM for a Higher and Better Use

Where are the two (newer) houses that you have sent images of? Even though you submit them negatively, I nonetheless find them intriguing. Are the two shown thus far close to one another? Are there more of the same ilk? I see them as very much descendants of Venturi and Rauch's Guild House (Philadelphia, 1966) as well as Venturi's Eclectic Houses (theoretical studies, 1977).

2000.03.06

reenactment in Philadelphia

1. the Merchant Exchange and the choragic monument in Athens--this also relates to Schinkel's...

2. Strickland's Second Bank of the US and the Pantheon (and hence the model for many subsequent American banks).

3. Girard College as a "true" Corinthian temple.

4. B.F.Parkway as the Champs Elysee/Place de la Concorde.

5. the 2nd Street church tower reenacting City Hall tower--also the church on south 22nd street?

6. the Art Museum on Fairmont reenacting the Athenian acropolis.

7. Franklin Court.

8. Welcome Park.

10. cardo and decumanus.

11. Guild House reenacting Ahavath Israel Synagogue.

2000.10.06 15:30

Re: architectural photography

I believe Paul refers to a webpage called "Panic Architecture" re: Venturi and Rauch's Guild House in Philadelphia, and his comments lead me to believe that Paul knows Guild House only through photographs. Besides seeing Guild House in person, the next best way to understand an architectural design is to study the drawings of the design, that's where the real intention is recorded, e.g., the chain-link fences of Guild House are very intentionally designed.

| |

2002.08.12 15:45

recent observations

As I was driving down Spring Garden Street yesterday, a detail of Venturi and Rauch's Guild House caught my eye. The white brick wall either side of the recessed entrance (in contrast to the red brick of the rest of the building) immediately reminded me of the new two-tone masonry at Ahavath Israel. As RE can confirm, from the first time I saw Ahavath Israel in 1998, I got the sense that Guild House was somewhat of a faint reenactment of the synagogue. Now one could say that the original is reenacting its reenactment.

Later, while touring Manayunk with a friend that had never been there, I couldn't help but notice the storefront display of the Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates office on Main Street. On the window is a big sign that reads "Learning From Everything" and in the display area is a ladder and saw and a smaller sign hanging from the ladder that reads "under construction." Do you suppose that the message there delivered is indeed for they and us to now "learn from everything under construction?"

Tomorrow, if the window display is still the same, I'm going to take a picture of it and title the picture Learning from Everything Being Incomplete.

2002.08.12 18:08

more reenactment than I thought

In just comparing images of Ahavath Israel and Guild House, there are several features strikingly similar between the two building:

1. the 'main' facades projects out to the street and stand in contrast to the adjacent building (elements).

2. the entrances are ground level recesses within the main facade. (Interestingly, Ahavath Israel had three columns later installed within the recess to augment failing support of the wall above, columns that are now removed due to the new facade work, while Guild House always had an exaggerated column standing within the recess.)

3. the three individual windows symmetrically framing the center balconies of Guild House very much echo the three sole windows to one side of Ahavath Israel's otherwise facade.

4. the cornerstone setting/detailing of each building is virtual identical, except for the dates, of course--5698/1937 vs. 1965.

I am now reminded of an anecdote R. told me the day after I took R. and S. to see Ahavath Israel some Sunday morning October 2000. After our visit to the Kahn building, R. and S. went to have lunch with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. They told the famous architects about having just seen Kahn's first building. Venturi apparently acted in some kind of disbelief, as if the building didn't even exist. He said something like, "But it's not even in the catalogue!?!" I assume Venturi was referring the Louis I. Kahn: In The Realm of Architecture. R. told them to look up the (then) webpages at www.quondam.com that displayed images of the building.

I was immediately suspect of Venturi's apparent lack of knowledge of the building. Granted 1965 is a long time ago, and we all have incomplete memories. Nonetheless, Congregation Ahavath Israel (original sign and all) was very much featured within Vincent Scully's 1962 book Louis I. Kahn.

[Now imagine the computer screen you're looking at right now as an incomplete window display somewhere in Philadelphia, and repeat to yourself for the next 28 years, "Learning From Everything Venturi Forgot."]

|