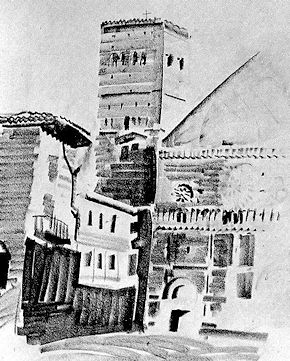

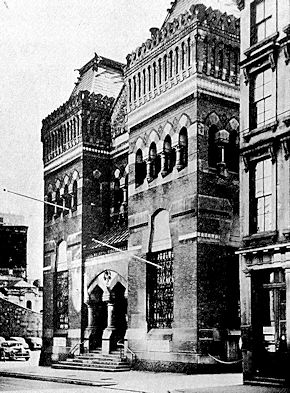

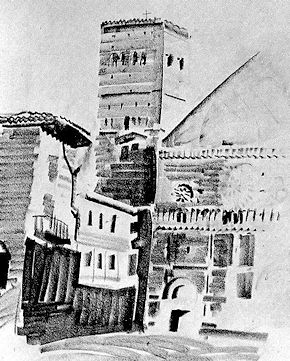

Siena. Sketch by Louis I. Kahn, 1928-29.

| |

"I recall the beginning as Belief." --Kahn, 1961

Ten years ago Louis I. Kahn, then over fifty, had built almost nothing and was known to few people other than his associates in Philadelphia and his students at Yale. None of them would at that time have called him great, although his students generally felt, with some uneasiness, that he should have been, even might have been, so. But within ten years the "might have-been" has turned to "is," and Kahn's achievement of a single decade now places him unquestionably first in professional importance among living American architects. His theory, like his practice, has been acclaimed as the most creative, no less than the most deeply felt, of any architect's today. He is the one architect whom almost all others admire, and his reputation is international. European critics have even insisted--so claiming Kahn as once they claimed Wright-that he has been seriously underrated at home.

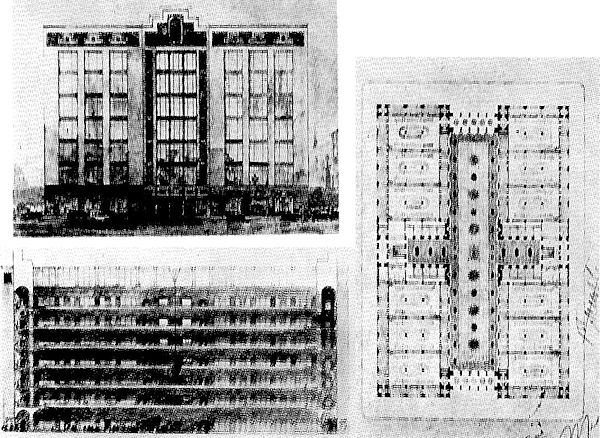

To begin to understand Kahn requires a major intellectual effort, and indeed it ultimately involves the rewriting of contemporary architectural history. A generation brought up on Hitchcock and Johnson International Style, of 1932, or even Giedion Space, Time and Architecture, of 1941, could hardly hope to perceive Kahn's quality at once. Nor could he, more importantly, have been able to find himself easily in it. From this observation, one of the major factors contributing to Kahn's lack of significant production during the thirties and forties comes to light. Kahn was, in large part, a part of that academic education, centered upon the French École des Beaux-Arts and called in America, generically, Beaux-Arts, whose later phases many historians of modern architecture, including myself, had so long regarded as bankrupt of ideas. In a formal, symbolic, and sociological sense the Beaux-Arts probably was bankrupt by the early 20th century, not least in the 1920's in America. But the researches of Banham and, more recently, of Stern, now force us to recognize the tenacious solidity of much of its academic theory, as distilled from Viollet-le-Duc and others by Choisy, Guadet, and Moore. That theory insisted upon a masonry architecture of palpable mass and weight wherein clearly defined and ordered spaces were to be formed and characterized by the structural solids themselves. One of the earliest extant drawings by Kahn, a student project of 1924, shows that he learned that lesson well--apparently better, as a comparison could demonstrate, than the other students of his time. Kahn's characteristic difficulty with the skin of his building, with, that is, the element which seemed to him neither structure nor space, is equally apparent in a comparison with other contemporary projects as, for example, with that by William Wurster, published at the same time. Kahn was also trained in the Beaux-Arts manner to regard the buildings of the past as friends rather than as enemies, friends from whom one was expected, perhaps with more intimacy than understanding, to borrow freely.

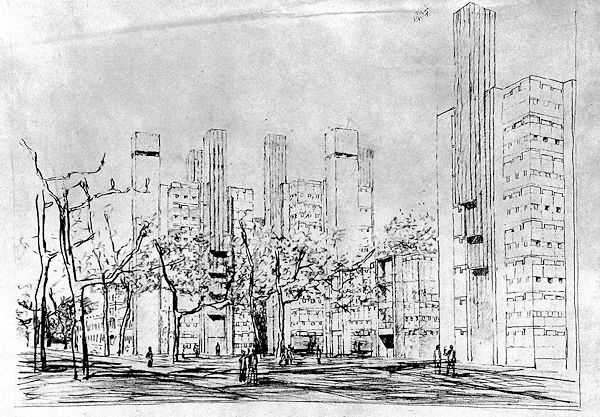

So trained, Kahn emerged during the late twenties into an architectural world where his lessons were not valued, neither by most Beaux-Arts designers (by whom, especially in America, the structural rather than the eclectic side of the theory was normally honored in the breach) nor by the livelier, more creative, and apparently iconoclastic architects of the Modern Movement. Soon called "The International Style," the new architecture of the twenties and thirties generally concentrated upon lightness, maximum thinness in the solids, and fluid spaces, usually defined not by the structural skeleton but by non-structural planes and skins of wall. In this world Kahn was never at home, and two decades of his life were given over to a not entirely successful attempt to find a place within it. So his few buildings and his drawings of the thirties and most of the forties often hardly seem to be from his hand, whereas his European sketches of 1928 and his perspective of the Richards Medical Research Building, of 1958-60, are clearly by the same man, one who can again create the forms to which he is instinctively drawn, his pencil constructing the two in an obviously related way. The later drawing is tauter and more articulate as to parts. It is that of a practiced constructor and a modern architect, but it also shows that Kahn could now use what he had originally been trained to see and to do. He had come into his inheritance.

The road back, and forward, began to open out for Kahn about 1950-52. That renewal also owed much to the pervasive influence of Le Corbusier and to a new direction taken by the Modern Movement as a whole during those years. But in the end the richness of theory and practice which Kahn has since poured forth stems intrinsically from the character of his own genius and from the life he has lived.

Kahn's father, now a lean and erect man of ninety, was a craftsman in stained glass and a sergeant in the Imperial Russian Army. His mother, who died only in 1958, was a harpist. While still a very small boy, Kahn was badly seared when the apron in which he was carrying hot coals from the communal fire flared up in his face. In 1905 the family emigrated from the Baltic island of Osel to Philadelphia, where they lived in profound poverty. Kahn's upbringing was wholly Jewish, though not strictly Orthodox, but as a boy he discovered and read the New Testament on his own. He has since said it was as if a sword had pierced him. "They've got us," he said, and buried it in the snow.

| |

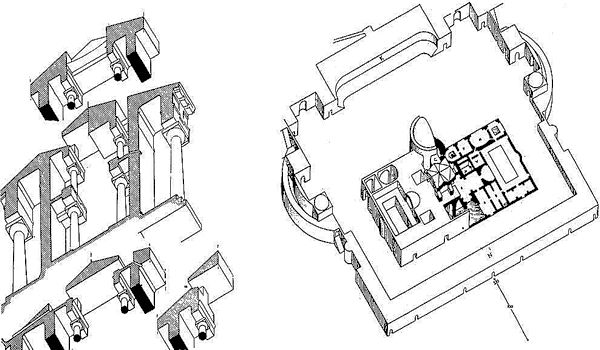

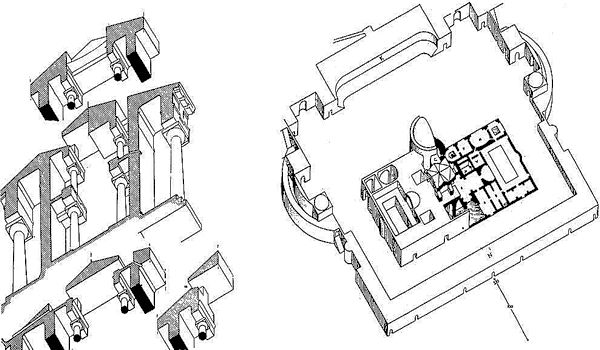

August Choisy. Axonometric section of a Greek temple.

August Choisy. Axonometric drawing of the Baths of Caracalla.

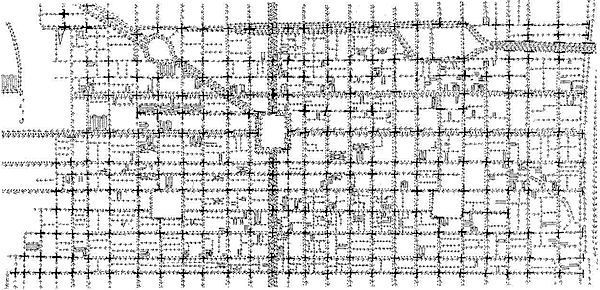

A Shopping Center. Plan and elevations. student drawing, 1924.

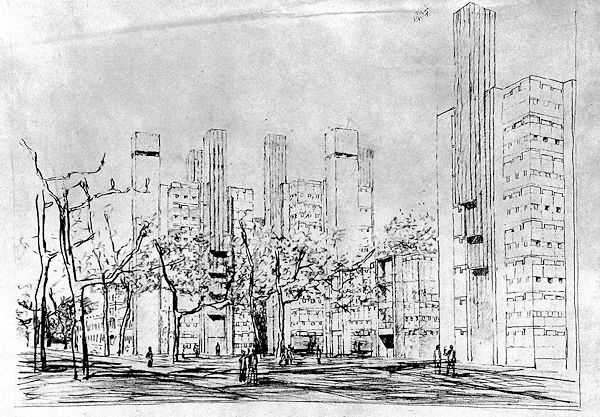

Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Building, University of Pennsylvania. Perspective drawing, 1960.

|